Faces of ALBA: The Family of Oiva Halonen

Eighty-six years after the last soldiers in the Lincoln Brigade left Spain, their legacy continues. As veterans shared their stories with friends and family, they shaped the lives of their children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. The family of Lincoln veteran Oiva Halonen, a Finnish-American volunteer, is one example.

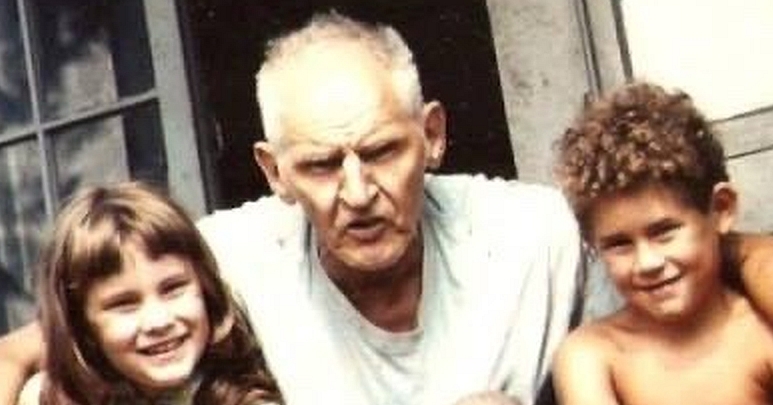

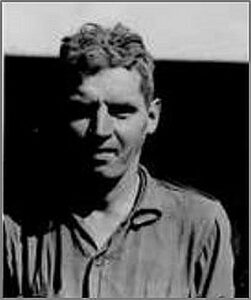

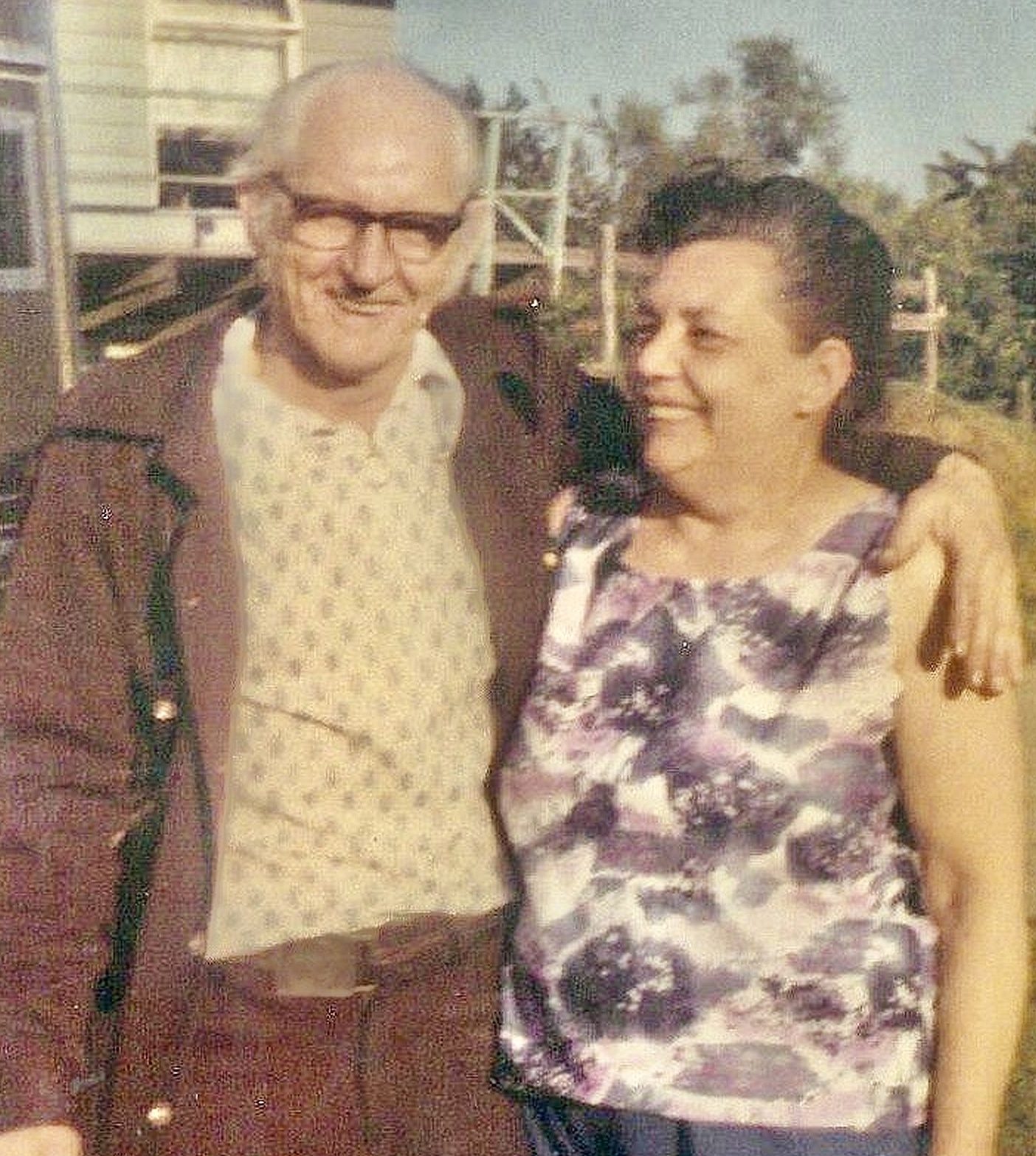

In 1937, a 25-year-old Oiva Halonen joined the volunteers in Spain as a machine gunner for the special battalion under Leonard Levenson. He fought until the end and then returned home to Seattle. Oiva and his wife Taimi Halonen had two children, Kae LaVerne Halonen (born in 1940) and Marie Ann (called ReeAnne, 1943-2010). They also had several grandchildren. Here we interview two generations of Halonens: Oiva’s daughter Kae, her daughter Simone Brennan, and Vincent Webb, who is a child of ReeAnne.

When did you learn that Oiva had fought in the Spanish Civil War?

Kae Halonen, daughter: The discussion of Oiva going to Spain was a normal part of life, alongside daily events and gossip shared over meals. What I remember most is the music. We had records from the war and Dad knew every one of the songs. After ReeAnne was born, Oiva was the one to put us to bed. He was deaf but he spoke English and Finnish well and he sang perfectly in tune. He sang “Quartermaster’s Store,” “Peat Bog Soldiers”, and “Viva La Quince Brigada.” He also sang Red Army Songs in Finnish. I listened to the talk of Spain with interest but not was clear about the history or its importance. I just knew that Daddy had done something to be proud of. Clarity came in the 5th grade. We were talking about the Spanish American War. I listened, raised my hand, and said “my Daddy fought in that war.” The teacher was silent for a moment, and she said: “Kae, your father could not be that old.” I said “Yes, he could. He’s over 30 now and that is old!” I went home and told my mom how dumb the teacher was. Mommy said: “the teacher is correct. Your dad fought in the Spanish Civil war which happened in the 1930s, and was part of the rise of fascism, Hitler and Mussolini and the Japanese.” That is when I realized that the Spanish Civil War was more than the songs, and an actual part of the history we were living.

Vincent Webb, grandson: I feel like I’ve always known about my grandfather’s involvement in the Spanish Civil War. It was something I always heard about as a child. My grandfather was thrown a huge party on his 60th birthday. I am certain that there were many Lincoln vets there and lots of memories were shared. I was eight at that time and I’m guessing that might have been my actual first introduction.

Simone Brennan, granddaughter: I can’t remember a time that I didn’t know about his participation in the Spanish Civil War. I suppose I became more conscious of what that meant; that is, what the impact was on him and how the rest of the family understood that history, as I entered my teens and young adult life.

Do you remember any stories in particular?

Kae: My dad was living in Washington when he decided to go to Spain. Our family came from northern Minnesota. My grandfather, George, had left Minnesota after workers lost a major strike in the iron ore mines. Finns, including my grandfather, could not find work. The owners focused their blacklists on the Finns because they were seen as troublemakers: too radical and dangerous. So, George left for the west coast looking for work and my grandmother Selma stayed in Hibbing with Oiva. Selma asked that George provide a home for my dad. Seattle had a general strike in 1919 and our dad sold the strike newspaper as a 9-year-old boy. From that point on, he went back and forth between Minnesota and Washington. Sometimes he hitch-hiked west; other times he hopped on a moving train. His decision to go to Spain created a battle at home. George had a new partner by the 1930s, Anni. Anni did not want Oiva to go and fight. George was silent until the last day. He finally said: “The boy is over 21. If he chooses to go to Spain, then he goes to Spain.” That ended the argument. George drove Oiva to the Greyhound Bus Station and asked him if he had any money. “Yep, 50 cents,” he replied. Ukki (grandfather) said: “Well that’s enough for a couple cups of coffee. Good luck in Spain.”

Vincent: One time my grandfather, who was deaf, got stranded in no-man’s land. Apparently, in the middle of the night his comrades were given the order to retreat but Oiva was asleep and did not hear the order. When he woke up there was no one around him and there was shooting above his head. Yet he somehow made his way back to his unit. Another time, Oiva had lost one or possibly both shoes. As he was marching with his unit, a vehicle drove past with a high-ranking commander. The vehicle stopped and the commander asked Oiva about his missing footwear. After Oiva explained how he lost it, the commander gave him the shoes he was wearing. They were much too big, if I remember correctly—but better than nothing.

Simone remembers the story a bit differently: Apparently the only size boots available that would fit him were size 16s—several sizes too large. He hated those boots. They were so heavy! One day there was a battle and one of the boots kept slipping so he threw it off and fought with only one boot. After the battle all the soldiers fell asleep. When they retreated, they forgot to tell Oiva. He woke up alone in no-man’s land and had to crawl and then run away with only one boot on, making a narrow escape.

Oiva seems to have identified strongly with his Finnish heritage. It helped to shape his political views as well. Did you see that growing up?

Kae: Finns divided into three primary groups: Church, Temperance and Reds. Our family was Red. Finns organized Finnish Halls throughout the United States. The Red Halls had discussions about socialism, organized dances, and athletic programs. They also presented plays and musical programs. Oiva met our mother Taimi in the hall Finns used in Seattle. He was working on the Grand Coulee Dam at the time. Our parents joined the Young Communist League (YCL) when they were old enough. He later taught classes at Finnish Hall. I remember watching my parents and friends in costume doing Soviet, Finnish, and American dances. They also performed in choruses and theatre, recited poetry, and discussed politics—all in Finnish. And I remember the sorrow once McCarthyism put an end to the Halls.

Vincent: My grandparents strongly identified with being Finnish and have instilled that in all of us. They often spoke Finnish in their house and subscribed to the Finnish newspaper the Tyomies, a long-running leftist Finnish-language newspaper run by immigrants. They were not only Finns but Red Finns, as opposed to the anti-Soviet White Finns. So being a Red Finn certainly helped shape their politics and views. Politics and social issues were always talked about at my grandparents’ home, no matter who was there. To this day I always get a little teary when I hear Finnish.

Simone: I was born and lived in Seattle until the age of three, when my mom (Kae) moved my sister Emily and me to Detroit. We didn’t have enough money to see our grandparents frequently but the trips we did make to Seattle were filled with stories of our radical Finnishness and that we were proud Red Finns. That is how I understood the politics of our Finnish culture. Those stories were enhanced by actual conversations with my grandparents. A couple of our vacations took place at Mesaba Park, outside of Hibbing, Minnesota. I was little but have such wonderful memories of that park and all the old radical Finns with stories, bonfires, and laughter. I also remember dancing the Schottische with Oiva, a Finnish polka type of dance. The take-away from these experiences is that radical Finns were fun and greatly honored in our shared history.

Like many veterans of the Spanish Civil War, Oiva was harassed during the McCarthy era and called to testify before the Committee on Unamerican Activities, HUAC. Did he talk with you about that time?

Kae: McCarthyism became a real part of our home. Oiva was called before HUAC. I had just started High School. Oiva’s picture was on the front page of both Seattle newspapers. I think our dad was a very handsome man, but the photo made him look mad and mean. The headline read: “Communist Youth Leader Takes 5th Amendment.” Mom was worried about what would happen to ReeAnne and me at school. She told us to come home if we got teased or threatened. We did not have to. Friends asked: “Is that your dad?” “Yep,” I said. They said: “How Cool.” Teachers were especially friendly. And while Oiva lost his job and was expelled from the machinist union, we did okay. Taimi found it ironic that when Oiva found another job it was at another union shop.

Vincent: Oiva did talk about the McCarthy period with me, but I think I heard more about that time from my mother ReeAnne. I remember Oiva explaining why he pleaded the 5th amendment while being interrogated. He said he had no problem answering any questions about himself or his beliefs. He was proud of who he was and what he stood for. However, if he answered a single question, it would open the door for interrogators to ask who else was involved. It was a difficult time and Oiva did not want to hurt anyone else during that madness.

I know that one of Oiva’s coworkers got angry and threw a punch at him. I’m sure he was told to “go back to Moscow” more than once. Oiva told me that people sometimes questioned his manhood because he was a peacenik or against the Vietnam war. He made it very clear to me that he was anti-violence and usually anti-war but that he was not a pacifist. He would only use violence as a last resort, but he would fight if he felt it necessary. Oiva was one of the most mild-mannered and humble men that I’ve ever known. I would not have been surprised if he had been a pacifist. But he clearly was not.

Simone: When Oiva went before HUAC, his picture was splashed all over the newspapers. He was a machinist and when he came into work, he found a hammer and sickle spray-painted on his locker. My mom also remembers that the FBI constantly surveilled them, parking outside the house. She told us that her parents hid the phone in the oven in case they were bugged.

Oiva’s wife Taimi participated in part of an oral-history interview that is now housed at the Tamiment Library. It appears that she was more politically active than your grandfather in the 1960s and 1970s. Is this correct?

Kae: Taimi was totally active in the community. She was often seen as a leader because she taught with kindness, knowledge, and warmth. Oiva worked as a machinist in several plants. He talked with people and listened to people. He always bounced back when attacked. One Christmas we went to Seattle from Detroit to be with family. When we arrived, I felt someone tapping my shoulder. I looked up and it was Oiva, with a huge black eye. I asked him what happened, and he replied: “Aww, some of the workers in my plant decided they did not like my politics. Put a Hammer and Sickle painting on my locker and my parking space.” “I went back to work to talk to them about who we should of be mad at to get through these hard times in capitalism.” “What happened then?” I asked. “Couldn’t ask them,” he said. “Got scared?” I asked. “Nope,” he said. “They got fired.”

Once he had retired, Oiva, together with Bob Reed, reactivated the Volunteers group, teaching about Spain, fascism and supporting progressive issues of today. He lived only four years after his retirement. He did not know that he received a letter of apology from the machinist union and was made a member once again of Local 79.

Vincent: My aunt Kae is the authority on this, but I thought they were equally active in politics. The difference was that Oiva was a quiet man and Taimi was a very good speaker. It always seemed to me that any political activities always included both Taimi and Oiva, although I do remember Taimi being very involved in Seattle women act for peace or SWAP.

Simone: If she was more politically active than him, it was only because he had a full-time job, and she didn’t. She also had a very different personality–more comfortable with public speaking and taking on “leadership” roles. She also made the decision to stay home with the kids and to engage in activism full-time. During his four years of retirement, Oiva collaborated with Bob Reed to document their and other vets’ experience with the Spanish Civil War. He also lived his activism in his non-working life. He lived it by being an active member of the Communist party, by participating in protests and activities when he could. If he had lived longer, I can only imagine what he would have accomplished.

How have you and your family been influenced by your grandfather’s experience in Spain and his political activism afterward?

Kae: My parents passed along the foundation for living with truth—recognizing that Marxism is a tool, not a dogma. Their actions taught me how to understand contradictions in a complicated society. They taught me that social change is not based on the smarts of a few but identifying the strength of a united many. It is about listening with respect and honesty and identifying priorities. It is to care deeply and encourage actions that move us forward to a truly inclusive dynamic democracy, a people’s democracy no longer responsible to individualism and wealth.

Vincent: I am not very active politically. I stay informed of the news and attend protest rallies on occasion. I am not involved in any organization at this time. I often share with my friends that my grandparents were in the Communist Party, and they often ask my views. I believe every human being has a right to food, water, shelter, healthcare, and an education. I’m certain that I heard my mom say this many times and I’m guessing that she may have heard it from her parents.

Simone: We moved to Michigan the summer of 1967, the year of the Detroit Rebellion (Riot). My mom was in her early 20s and wanted to find her own way in the world, and not live in the shadow of her parents’ activism and legacy. Detroit was becoming an area with a lot of activism and that, coupled with what she witnessed during the rebellion, solidified her decision to stay. We lived on Hancock and Canfield (which was in the middle of the rebellion), and she witnessed the ways in which community folks supported one another during this tough time. She had never seen anything quite like this in Seattle.

As a grandparent/great-grandparent, I think she understands better now than she did in her younger days how hard it must have been on her parents (and on my sister and me) not to live in the same state. To a certain degree she’s right, but I couldn’t love a city more than I love Detroit, so I’m glad we are here.

The very foundation of my upbringing is based on doing what is in the best interest of humanity – who you are and the actions you take are not separable. There have been times when I have felt guilty because I haven’t been as much of an activist as my grandparents or my parents—at least, my activism didn’t always look like theirs. What is true is that like them, I have taken on issues in my workplaces and among my social circles when the situation called for it—in some cases, when doing so was unpopular. I have been active in my kids’ schools (when they were younger), with community groups, with various social causes and with the AFT Union. I participate to varying degrees with political candidates I support. I think the most important thing I have done is share Oiva’s stories with my kids, hopefully helping them understand their place in this world, knowing that doing what is kind, humanitarian, and fair means you’re sure to be grounded to the earth and the people, honest with yourself and clear about your decisions. I have a grandson now. Once he can talk, I can start sharing Oiva stories with him.

How are you passing down your Oiva’s legacy?

Kae: As a grandmother, I want my kids, grandkids, and great grandkids to know that true bravery does not mean that you are loud and proud. Heroism is often a quiet look at what needs to be done and doing it. Oiva and many of those that went to Spain were proud to be premature anti-fascists. We need more Oivas and Tamis today.

Vincent: Over the years I have protested racism, war, apartheid, gun violence, and so forth. I am so proud of my grandfather. I have more respect and admiration for him than any man I have ever met. I feel so lucky to be a part of this family. During the last few years, I’ve had to explain that ANTIFA stands for anti-fascist to quite a few people. I start with Oiva being labeled a premature anti-fascist and go from there. I always say I am antifa at heart. When the freedom foundation starts harassing me and my coworkers, I make sure to explain why unions matter and why we need to stick together. I will be protesting the Supreme Court’s ruling on Roe v. Wade every chance I get over the next few years. These are just a few ways I pass on what I’ve learned from Oiva. I could go on and on. Mostly, I’m so grateful that my grandfather showed me what a loving, kind, honest and ethical man looks like. I could never live up to what he accomplished but I’m so thankful that he helped raise me.

Simone: I have nothing but the utmost respect for my grandparents. I am grateful beyond measure that my mom and her sister continued to share the stories and culture of their parents. I am grateful for my family.

Aaron Retish, ALBA’s Treasurer, is a Professor of History at Wayne State University.