Book Review: Chim Seymour’s Humanist Gaze

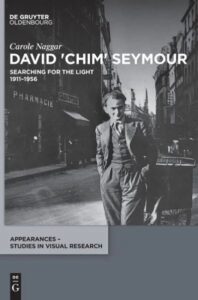

Carole Naggar. David ‘Chim’ Seymour: Searching for the Light, 1911-1956. De Gruyter, 2022. 294 + x pp.

Carole Naggar. David ‘Chim’ Seymour: Searching for the Light, 1911-1956. De Gruyter, 2022. 294 + x pp.

In late September 1948, the photographer Dawid Szymin wandered through the Warsaw neighborhood where he’d been born 37 years earlier (when Poland was still a province of czarist Russia) and where he’d lived most of the first 21 years of his life. Yet judging by the photographs he took, “neighborhood” is too generous a description. After the German occupation, the street where he’d grown up had become part of the Jewish ghetto and was then razed in response to the 1944 uprising. Four years later, the images show a desert of debris as far as the eye can see, with some rudimentary roads running through the piles. “All the buildings have been completely wiped out, blown up by dynamite,” Szymin wrote in the caption, “and the streets [are] completely covered with rubble. A few main thoroughfares have been cleaned.” The only two structures left standing were the church and the school.

Next, Szymin took the train to Otwock, a resort town 15 miles to the southeast, where his family would spend their summers and where his parents had co-owned a small bed-and-breakfast. Throughout the war, Dawid and his sister had hoped and prayed that their parents might have survived the Holocaust. But it turned out that they, along with his mother’s sister, had been shot by the Nazis in Otwock in August 1942. Six years later, Szymin was surprised to find that his parents’ bed-and-breakfast was still there, turned into an orphanage for war victims. But while he had his cameras on him, and in fact was on assignment for UNICEF to document the lives of children in postwar Europe, he did not take a single picture. “Sometimes, the absence of an image is just as telling as its presence,” Carole Naggar writes in her biography of Szymin, “and trauma can only express itself in silence.”

A lot had changed since 1932, when Dawid had left for Paris to study at the Sorbonne. For one, he now carried an American passport that identified him as David Seymour, although his friends had long known him as Chim (pronounced shim). In Paris, he connected with fellow antifascists, became a photojournalist, and enthusiastically documented the rise of the Popular Front. He first traveled to Spain in early 1936, months before a failed military coup would unleash a civil war. Chim’s photographic coverage of that war would make him world famous, as it did his friends Gerda Taro and Robert Capa—like him, young, progressive Jewish refugees of fascism. (Gerda died, crushed by a tank, in 1937.) In 1939, Chim accompanied Spanish exiles on a boat to Mexico; he then immigrated to the United States, served in the US army as a photographic analyst during World War II, and traveled through postwar Europe to document the damage done and attempts at reconstruction.

In 1947, Capa and Chim, together with George Rodger and Henri Cartier-Bresson, founded Magnum, a groundbreaking cooperative that sought to empower photojournalists in their relationships to editors and publishers by allowing them to retain copyright, receive proper compensation, and protect the integrity of their images and captions. Over the next seven years, Magnum grew into what it is today: one of the world’s premier agencies and a force for progressive innovation. Yet photojournalism is a dangerous profession, and in the mid-1950s Magnum suffered three heavy losses. Capa died in May 1954 on assignment in Indochina when he stepped on a landmine. Nine days earlier, Werner Bischof had dropped to his death off a cliff in Peru. Two and a half years later, while covering the Suez crisis, Chim and a colleague were killed by Egyptian soldiers while driving their jeep along the canal.

Although he was not yet 45, Chim left an impressive photojournalistic oeuvre that included everything from wars and refugee crises to labor protests, postwar reconstruction efforts, folk rituals, and celebrity portraits. From the outset, two threads ran through his work: sheer technical ability—Chim had an uncanny sense for photographic composition—and a deep empathy for his subjects, especially women and children.

Born into a well-to-do Polish Jewish family, Dawid Szymin grew up surrounded by high culture. His father, a prominent publisher of books in Yiddish and Hebrew, took the family to Odessa when the Great War broke out, returning to Warsaw in 1919. Ten years later, Dawid went to Leipzig to study graphic arts—Bauhaus was all the rage—and then moved to Paris to study chemistry and physics, knowledge to be applied to his professional future as a printer. He got drawn into photography instead.

No one knows more about David Seymour than historian and curator Carole Naggar, who has studied his life and work for decades. Her long-awaited biography, handsomely edited by De Gruyter, provides a detailed, near-exhaustive overview of Seymour’s four and a half decades on this earth, primarily guided—starting in the 1930s—by his contact sheets and publications. The book, moreover, contains more than a hundred excellent reproductions that bring home the extraordinary power of Chim’s photographic gaze. Despite some pesky factual and spelling errors, Naggar does a good job providing the historical context for the main chapters of Seymour’s life (from pre-war Warsaw, Leipzig, and Paris through the war years to postwar Italy) and his many assignments (from Popular-Front France to the Middle East), while placing his work as a photographer, and visionary, trouble-shooting leader within Magnum, in the history of modern photojournalism and the broader cultural context. (It was Chim, Naggar suggests, who invented the term “Generation X” to designate those born after the atomic bomb.)

While the bulk of the chapters consist of chronological descriptions of the images Seymour shot on his many assignments, Naggar also draws on his correspondence, and on interviews with those who knew him, to paint a portrait of Chim—who began balding early, liked to eat well and had a buddha-like air—as a charming, empathetic, infinitely curious man who rarely let on how much he suffered under the weight of his trauma, and who insisted on downplaying his own talent. (To be a good photographer, he once said, “all you need is a little bit of luck and enough muscle to push the shutter.”) As a photographer, Chim was a master at making himself invisible, when necessary, at the same time that he could establish an immediate connection with the people he photographed, whether they were orphans, movie stars, factory workers, artists, or illiterate peasants. Yet as comfortable as he was looking through his viewfinder and chatting up his subjects, Chim was also quite reserved. He did not care to share details about himself with his family, friends or colleagues. “He remained secretive about his personal life—especially his girlfriends—”, writes Naggar. Faced with this lack of information, she’s left to speculate not only about Chim’s romantic attachments but also, often, about his mental state, whose fragility he seemed to channel into photographic sensitivity. “Chim picked up his camera the way a doctor takes his stethoscope out of his bag, applying his diagnosis to the condition of the heart,” Cartier-Bresson wrote, adding: “His own was vulnerable.”

This nebulousness about Chim’s inner life extends to his political convictions. Here Naggar is perhaps vaguer than necessary. While she makes clear that Chim was a fellow traveler before World War II (“as far as we know, he never joined the Communist Party, but he was definitely a sympathizer with socialist causes”), she says little about his relationship to the Communist movement after 1945, as the Cold War intensified, beyond suggesting that he felt disillusioned, possibly because of the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, which of course comprised his native Poland. Readers are left to wonder whether Chim’s close friendship with the painter and writer Carlo Levi—an antifascist who kept some distance from political parties but nevertheless ran for the Italian senate as an independent on a CP ticket—included a deeper political connection. Rather than pinpointing Chim’s position on the Cold War map, Naggar rather loosely summarizes his postwar politics as “humanist” or “humanitarian.” (To be sure, Chim was a pioneer when it came to mobilizing the photographic image for NGOs.)

The biography is clearer about Chim’s position on Israel, which he visited often from 1951 on and supported rather uncritically, failing to acknowledge the suffering of displaced Palestinians. “In many ways,” Naggar writes,

Israel, and the communal life of the kibbutz, embodied Chim’s ideal of a political utopia, fusing solidarity, a melding of nationalities, a pioneering spirit, and fervent idealism. It also represented his fervent hope of healing his life after the Shoah. As he wrote to his sister, “It was like coming home again. It was like picking up the living threads of my life, for which I had been searching in vain on the heaps of rubble and ash in the ruins of Warsaw.”

Chim, who moved breathlessly from assignment to assignment, never got around to properly curating his own work. After his untimely death, that task was taken up first by Magnum colleagues like Cornell Capa and Inge Bondi and, later, by his family (Ben Shneiderman and Helen Sarid), Cynthia Young at the International Center of Photography (with an impressive retrospective in 2013), and of course Carole Naggar. Her excellent biography should serve to rekindle the public’s interest in one of the most compelling photographers of the twentieth century.

[…] Full text at The Volunteer. […]