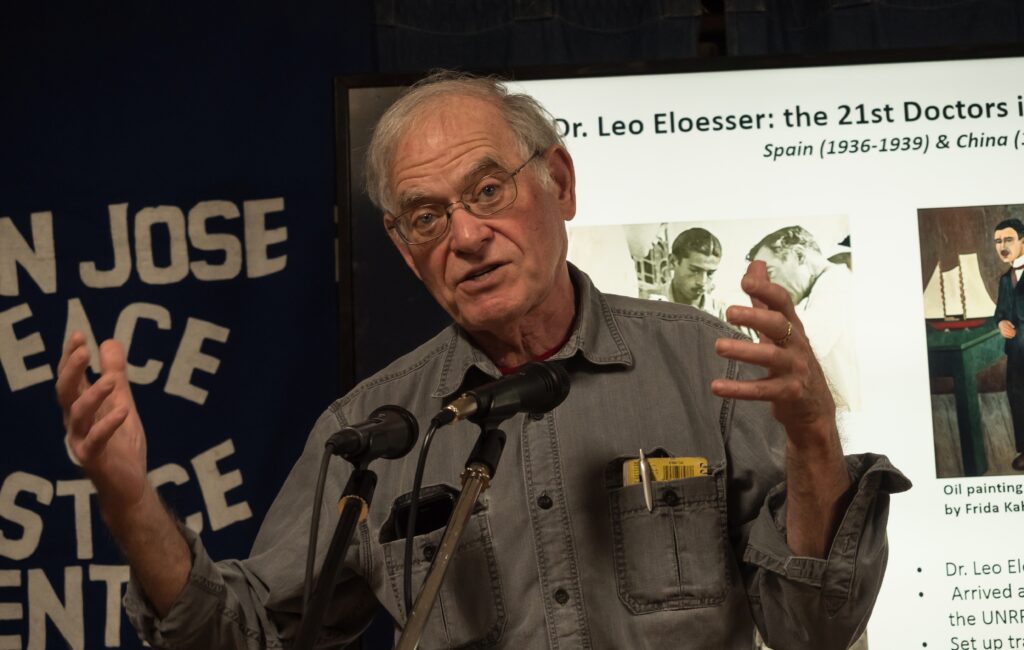

Peter N. Carroll: “I’m an Anarchist.”

Peter N. Carroll—renowned historian, poet, and (co-)editor of this magazine for more than twenty years—has been involved with ALBA for four decades. Time for a tribute: an interview (below); a piece by Dan Czitrom on Carroll’s years at the ALBA helm; a series of shorter tributes from colleagues; and two poems.

Peter Carroll, future historian of the Lincoln Brigade, was about to turn 14 when he first suspected he might be a red diaper baby. The idea horrified him—it was the height of the Cold War.

On an October evening in 1957, the day the Russians launched the first sputnik rocket, Peter and his father, Louis, happened to be driving past the United Nations building in New York. “They kept the lights on late,” Louis said. “They must be worried.” There was something in his tone that disconcerted his teenage son. A couple of months later they were talking at the kitchen table when Peter made a disparaging remark about “Communist dupes.” His dad looked him in the eye, grinned, and said: “You should know that your father was a red.”

Peter was shocked. “He might have punched me in the stomach,” he writes in his 1990 memoir, Keeping Time. The truth was that he didn’t know what to do with the information and explained it away. “I assumed that communism was merely a part of his youth, somewhere between childish and naïve, and that he was as embarrassed as I was by the past,” he writes. “In any case, it seemed safer—politically, psychologically—to let the matter rest. I was terrified that someone might find out.”

Fourteen was also the age that Louis Carroll, an academically and musically precocious son of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, had graduated from high school in New York City. It was 1929. After the Great Depression hit that fall, Louis found himself making a living as a nightclub piano player and gigging with his older brother’s band. A talented composer and arranger, he founded a music production company, got involved in left-wing politics, and in 1934 married a Jewish girl, a child of immigrants like himself. Their son Peter Neil was born nine years later. After a wartime stint in the army, Louis Carroll swapped the unstable music business for a steady job as a music teacher at a New York City junior high school. His political past was buried.

“I never got any more clarity about it,” Peter Carroll, now 78, told me when we spoke in December 2021. “In retrospect, I assume my father was in the Young Communist League, but I’m not sure. The next time I had a serious discussion about politics with him was in the mid-sixties, when I was in getting my Ph.D. I was taking a seminar on US diplomatic history. At that time, it was common wisdom among historians that the United States had fought Britain in the War of 1812—whose 150th anniversary had recently prompted several new books—to protect its national honor. I said something connecting that same idea with Lyndon Johnson’s stubbornness on Vietnam. My dad countered with a Marxist kind of analysis. Once again, I felt embarrassed.”

And yet Peter’s own views were about to shift. As an undergraduate at Queens College, he was on the editorial board of the student newspaper, The Phoenix, which challenged the administration for banning left-wing speakers (the Communist Ben Davis and Malcolm X) by organizing a strike of classes for free speech. Soon afterward, an editorial against the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) led the college president to punish the editors with “disciplinary probation, with warnings of potential expulsion.” It was his first taste of McCarthyism.

Like his father, Peter was academically precocious, enrolling in college at 16 and entering graduate school on a fellowship, at Northwestern, when he was 20. Three years later, he’d finished his dissertation on Puritanism and the American Wilderness; he landed his first academic job, at the University of Illinois, Chicago, in 1968—just as his thesis was being published. A few months later, he was hired at the University of Minnesota with full tenure. The lightning-quick transition into academic respectability—not to mention life-long job security—coincided with further political awakening. “The more I became concerned about the Vietnam War, the more my landscape broadened,” he told me. “I realized that there were interests involved—exploitative capitalist interests—and that the domino theory was not just about the evils of communism, but really an urge for capitalist expansion. By the time I got tenure, I was actively antiwar and pretty involved in the civil rights movement.”

Your father died young, in 1976. Did he ever tell you anything more about his own political past?

Very little. I got some more details from my mother in the years after his death. She told me they had attended political events together, including meetings on the Spanish Civil War. My father’s older brother had been a communist and had many close friends in the International Brigades. My guess is that my father followed his brother, whom he admired, into the party. But I could never ask my uncle directly because he died in 1958.

Why was your father so coy about his politics?

It was pure McCarthyism. Don’t forget that to be a teacher in New York City he had to sign a loyalty oath. I have a childhood memory of moving apartments in the Bronx. My dad had been boxing up his books. His father-in-law, who was a life-long socialist and union man, would come around the house around supper time. One evening, as my grandfather was leaving, my father handed him a bag full of pamphlets and books. I remember he told him to get rid of them, but to be sure to drop them in the trash further down the street so nobody could tell where they came from. He was cleaning out his left-wing stuff.

Did he steer clear from politics after the war?

Not quite. At his school, he helped create the teacher’s union and led the first strike of public-school teachers in New York City in April 1962. I was an undergraduate at Queens College by then. I remember asking him if he wasn’t worried about losing his job. He replied that for him it wasn’t a matter of choice, but of being able to face himself in the mirror every day. (Interview continues below.)

Peter Neil Carroll was born in New York City in 1943 and grew up in the Bronx and Queens. After graduating from Queens College, he received his doctorate in History from Northwestern University in 1968. He taught at the University of Minnesota until 1974, after which he worked as a book reviewer for the San Francisco Bay Guardian and other venues, and as an adjunct lecturer at Stanford, among other universities. Carroll is the author and editor of some 20 books, including Puritanism and the Wilderness: The Intellectual Significance of the New England Frontier (1969); The Free and the Unfree: A New History of the United States (1977); Keeping Time: Memory, Nostalgia, & The Art of History (1990); The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Americans in the Spanish Civil War (1994); and We The People: A Brief American History (2002). Since 2008, he has published eight volumes of poetry, including A Child Turns Back to Wave and This Land, These People, both of which have won the Prize Americana. Carroll chaired ALBA’s Board of Governors from 1994 until 2010; he continues to serve on ALBA’s Board and co-edits its quarterly magazine, The Volunteer. He also chairs the Advisory Committee of the Puffin Foundation and the Activist Gallery of the Museum of the City of New York. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with the photographer and writer Jeannette Ferrary.

Let’s go back to your time in Minnesota. It’s 1969, you’re 25, and you’re a tenured professor. That must have been some sort of record.

Yes. I think I might be the youngest person ever to get tenure at a US history department.

But then, five or six years later, you decide to resign and make a living as a freelancer. That strikes me as a remarkably nonconformist gesture for someone who, until then, seemed to be on a perfectly conformist path—and an accelerated one at that. How did the academically precocious kid and brilliant historian who was embarrassed about his father’s politics become such a rebel?

At Minnesota, I’d become politicized, both inside the university and out. I enjoyed teaching and doing research but ultimately, I wasn’t happy being an academic. Tenure had come easy—my first book came out almost immediately, and at the time, that was that—and seemed easy to give up.

In your memoir, you write: “My future was so secure that I had no future at all.” You felt burdened, you write, by “the incongruities of my professional identity, the image of the scholar”: “I was always embarrassed by the luxuries of the lifestyle and the dubious value of the work. I always felt like someone living unfairly on welfare.” But you also suspected that your discontent might be generational.

Yes. In fact, I spent the last year of my tenured academic appointment on a fellowship interviewing 25 former classmates of mine from grad school, most of whom by then were about ten years out. I wanted to find out why I had gotten myself so stuck in academia and why I was now so uninterested in it. As it turned out, about half of the people I talked to had switched careers.

What else did you discover?

For one, all the professors, men and women, had little studies in their house: once they closed the door, nobody could bother them. None of the non-academics had dens like that. Also, among my cohort group, only the academics had gotten divorced at that time. I realized that the academic world was very selfish.

Do you mean selfishness as self-serving or as self-isolating?

Both. It was a selfishness cloaked in academia’s sense of self-importance. These professors of history all thought themselves more important than other working people. You have to remember that in the early 1970s, the university was still a very traditional, male-dominated world. My education at Queens College and Northwestern, too, had been very traditional. I’d learned nothing about Black history, for example. No women’s history or Native American history, either. I had to learn those fields after graduate school, also because by then my students demanded it.

And you did.

Of course. Just look at my books, including my survey of US history, The Free and the Unfree, which I co-wrote with David Noble in the mid-1970s. In fact, I still try to keep up with those fields.

Yet your first book was on the colonial period.

Technically, my field was US intellectual history. What I really wanted to do was to work on the nineteenth-century philosopher William James: the idea of a closing frontier and how he was responding to that with the idea of an open-ended universe. But to satisfy my curiosity, I had to go back and start in the seventeenth century, when white settlers from Europe first came to America. Stupidly, that meant I was automatically classified as a colonial historian. But that wasn’t my love.

How did you end up writing about the twentieth century?

After resigning from Minnesota, in the mid-1970s, I moved to California and started looking for freelance gigs. I ended up as a badly paid, one-course adjunct at San Francisco State while working as a book reviewer at the same time. That didn’t pay well either, but I could scrape by doing a lot of reviews—and those were often on books about twentieth century topics.

Is that how you ended up connecting with the veterans of the Lincoln Brigade?

Wait, you are skipping an important chapter here. You’re not asking the right questions. (Laughs.)

Right. Do I remember correctly that you first made a trip to Spain?

That’s correct—and the key to that trip is a woman. See, I’d been married young, even before starting graduate school. That first marriage had ended in divorce. After leaving my job in Minnesota, I lived in London for a while doing research on psychohistory. In 1972, a woman I’d met in Minneapolis, who was of part Irish and part Gibraltarian descent, suggested I join her on a trip to Spain—Franco Spain. I’d never been to the country and did not speak the language. In high school, I’d studied French. We traveled around Spain for about five weeks. I fell in love with the country—and with the woman as well. From then on, back in the Bay Area, I took every chance I had to review new books about Spain. One of the first was Guernica: The Crucible of World War II by Gordon Thomas.

So you arrive at the Lincolns by way of Spain.

Exactly. In 1975, the San Francisco City Magazine, which had been founded by Francis Ford Coppola, the filmmaker, asked me to do a feature on the San Francisco Book Fair. There I came upon Alvah Bessie’s Spain Again, which had just been published, as a pair of paperbacks, with a reedition of Men in Battle. I interviewed Bessie. Bessie invited me to a screening, at someone’s home, of Abe Osheroff’s film Dreams and Nightmares, where I first met Milt Wolff and other Bay Area vets. Ed Bender then invited me to attend the annual reunion of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB), which was always held in February, around the anniversary of the Battle of Jarama. There, I met Jack Lucid. Him I also interviewed; he died a few months later. Shortly after, I did oral histories of two African American vets, Luchelle McDaniels and Vaughn Love, as part of an oral history project called the Radical Elders.

At the inauguration of the Lincoln Brigade monument in San Francisco, with mayor Gavin Newsom. March 30, 2008.

Was it hard to get them to talk to you as an outsider?

By then, the vets knew who I was. I’d been coming to the reunions and other events, and I’d written about them in the Bay Guardian. Plus, by the early 1980s, the vets realized they were getting old. There were more and more illnesses, even funerals. The Bay Area post decided to found an Associates’ organization, for which they picked about six or seven of us. It turned out that at least five of them were active members of the Communist Party, but I didn’t know that at first.

ALBA existed by then already, too, correct?

Yes, it did, but I didn’t hear about it until much later. In any case, at one of the first meetings of the Bay Area post with us Associates present, one vet started saying he didn’t like the idea of having associates. Others told him to shut up, since the matter had been voted on and settled already. By happenstance, I had another appointment to go to, so I’d planned to leave early, and I did. But the vets thought I’d walked out because I was insulted. Next thing I knew, I received a couple of nice letters, including one from Milt Wolff, asking me to reconsider my decision. (Laughs.) So that gave me an in as well.

What kind of work did the VALB Associates do?

I remember we picketed the Democratic National Convention in 1984 because the vets were seeking their benefits as World War II veterans. I was also involved in the 50th-anniversary celebration in 1986, which was organized in New York by Bill Susman and ALBA, with a great show that Bill Sennett and I helped bring to California. And then we raised money to send ambulances to Nicaragua. The idea for that had come from Ted Veltfort, a vet who’d been an ambulance driver in Spain. All that took a lot of time and energy, but I loved doing it. It left me very satisfied.

When did it occur to you that you could write a history of the Lincoln Brigade?

One day, Milt Wolff called me up to tell me his ex-wife had just sent him three boxes of old papers. I could have them if I wanted them. Of course, I said yes. He brought them over, dumped them at my front door and said: “You do whatever you want with them, I don’t care.” They included photocopies of every letter he wrote home during World War II. That’s when I realized I had a book in me.

Did Stanford University Press say yes right away?

It wasn’t Stanford at first. Through my agent, I had an advance from a trade publisher that allowed me to start working: do interviews, collect materials, visit archives—including, of course, the archive at Brandeis that had been gathered by Victor Berch, who knew more about this stuff than anybody.

What happened with that initial publisher?

They thought there wasn’t sufficient interest in the Lincoln Brigade. So then Peter Stansky at Stanford, who had written a book about Orwell with Billy Abrams, who was my editor, brought me into Stanford University Press.

By then your book was already done.

It was. But in the six-month delay caused by the publisher switch, the Moscow archives opened and I rewrote a couple of sections. The Odyssey of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade came out in 1994.

As Hemingway learned the hard way with For Whom the Bell Tolls, the vets are not easy to please. How did they receive your book?

Well, they called a meeting! (Laughs.) Of course, there were complaints. One widow said I’d made fun of her late husband because I’d printed the little diddy that his fellow soldiers had made up about him, things like that. But Robert Colodny, who was a legitimate historian at the University of Pittsburgh, wrote a tremendously positive review, comparing my Odyssey to Homer’s Illiad. After that, I remember the vets calling me up: “Guess what? We accepted you!”

Did they?

Not everybody did. I had little falling out with Ralph Fasanella because I’d written that he had deserted. The thing is, he’d told it to me himself, on tape. And I had corroborating evidence from about 15 other sources—who all added that Ralph was a good guy and they didn’t give a damn about it. The book did well. For several years, it was Stanford’s best-selling title.

If you could write another book on the history of the Brigade now, thirty years later, would you change the story in any major way?

No, although there’d be a lot of minor additions that’d be of interest.

Would it be different to write about the vets without them looking over your shoulder?

Not really. I didn’t let that stop me then, either. The rules were clear, and I could rely on my journalistic ethics. A couple of people requested not to be named by name, and some, like Harry Fisher, withheld documentation from me—including a contemporaneous letter from him about the death of Oliver Law, which he had witnessed. I never got clean with him about that.

Is there new research that would compel you to change the arc of your narrative?

Again, not in a big way. I still believe, as I did then, that had Britain and France intervened in the Spanish war on the side of the Republic, there may well not have been a World War Two. Then again, you never know. Other things that I suspected then are clearer now. For example, the fact that the Brits were quite happy to have Mussolini tied up in Spain because they thought it’d weaken the Axis powers, should war come with Germany.

And beyond geopolitics? Has your vision of the vets’ politics or ethics evolved since the 1990s?

I think there were some veterans who were fanatic or loyal Communists who made some strategic errors. Talking to Milt Wolff over the years, he admitted the VALB endorsed some things they shouldn’t have. On the other hand, the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade were the only left-wing organization that wasn’t wiped out during the McCarthy period.

Was that due to the sheer grit of the vets?

Of some of them, yes. They were tough. At the time ALBA was founded, there was a rival organization led by Pete Smith. I am not clear on what its vision was exactly, but it was different from what Bill Susman and his group wanted to do with ALBA. Still, it’s telling that ALBA’s original bylaws specify, in their very first paragraph, the mechanism by which, and under what circumstances, a member can be expelled! (Laughs.) In fact, around the time ALBA was founded, in the late 1970s, the VALB was in crisis because the Communists and the anti-Communists were constantly at each other’s throats over issues such as Israel. Things got really messy. At that point, they resolved the crisis by deciding that the vets, as an organization, would only be involved in three things: issues related to Spain, the vets’ personal needs, and the history of the Lincoln Brigade.

In addition to the Odyssey and your other books and essays on the Lincolns, you’ve also written about them as a poet. What’s the difference for you between the historical and the poetic mode of writing?

The source for poetry is the other half of my brain, the creative side. Which is not easy to access. When I pick up a pen, my first instinct is still to start writing prose. I often have to read poetry, others’ poetry, to get my head in the right place. But then something will start to cook. It’s an emotional thrust. Do you remember the first section of my poem “The Wound in the Heart”, that starts out: “Mayday, the earth warms, greens, a trumpet on the car radio / bleeds, Miles Davis’s, Sketches of Spain, the drama of rebirth”? What happened was that I was sitting in my car waiting for a fellow poet to come out of his house because we were going somewhere. Then Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain comes on the radio, and instead of getting out of my car, I waved my friend in. We just sat there and listened to the entire thing. That brought back everything you could imagine.

You also have touching poems on Milt Wolff and Jack Lucid.

It’s part of my love life. That’s really what it is.

If you were a precocious academic, as a poet you’re more of a late bloomer. Your first collection of poems, Riverborne, came out in 2008, when you were in your mid-60s. When did you start writing poetry?

I wrote poetry in fragments when I was in graduate school, not a lot, and very influenced by Allen Ginsberg. Too many words, too much testosterone. Then in 2000 I had heart surgery. I was planning a book on Ginsberg and his times—the same way people have written about Walt Whitman and his times. In fact, I’d started working on that project, which I gathered would take me about five years to finish. But then, after my surgery, I decided I could not afford a five-year plan. I thought I’d try poetry instead. I joined a couple of workshops and got the idea for a trip down the Mississippi, which became Riverborne. I got about 40 rejections before the right guy picked it up and published it. Poetry is now what I’m writing primarily.

You left academia almost 50 years ago. But you never stopped writing and teaching—still a pretty academic kind of life, if you ask me.

Yeah, but I haven’t been on a committee, or even attended a committee meeting, for any purpose! (Laughs.) And that saves an awful lot of one’s lifetime.

It’s not like VALB and ALBA don’t have committees…

The point is that there is no bureaucracy in my life. I’m an anarchist. I choose where I want to be and what I want to do, most of the time.

How about teaching? You’ve taught high school teachers since the 1970s and offered an annual course on film and history at Stanford for close to forty years.

I’ll tell you the truth. I was very fortunate to have taken a couple of courses at Queens College from the philosopher John McDermott. He changed my life. And you know what? That’s exactly what everybody says who has been a student of his at one point or another—or at least that’s true for the 50 or so of them that I have talked to. When I first met McDermott, I was a C student. I didn’t know what I was doing. McDermott made me serious.

He set you straight.

Yeah, he did. In fact, I dedicated Keeping Time, my memoir, to him. When it came out, in 1990, I thought I’d send him a copy. He was teaching at Texas A&M at the time. Then one day I got a phone call in the morning. “Is this Carroll, Peter Carroll?”. “Yes,” I said. “I don’t know who you are,” he said, “but thank you.” And then he went on to tell me a very sad story: His wife of 42 years had left him, his children had him arrested for drunkenness and alcoholism—for his own protection, because in Texas you can do that—and he had just got out of six months of rehab when my letter arrived with the book. “I love you,” he said. We became very close friends. He died in 2017. But what I wanted to say is this: Since 1968, I never once walked into a classroom without saying to myself: I have to be as good as McDermott today.

[…] Full text at The Volunteer. […]