Radio Music in Civil-War Madrid

The Spanish Civil War is often viewed as the first in which radio was used as a political and military weapon and an important instrument of propaganda. Apart from its use to motivate troops and demoralize the enemy, it informed the population with an immediacy that was impossible for the press to replicate. The radio provided a welcome means of entertainment and distraction amid the devastation and hardship. But what role did radio music play in the conflict and what type of music was heard in the capital during the war?

The origins of the radio in Spain: Unión Radio

The origins of radio in Spain date back to the early 1920s. At that time, all radio stations were privately run and listeners required to pay a fee—making ownership of a device closely linked to social status. The number of private receivers in the country was relatively low (around 300,000 for a population of 24 million by 1936). Nevertheless, people often gathered in bars, restaurants, social clubs, and union organizations to listen to the radio. Loudspeakers installed in the streets and public spaces, including schools, hospitals, and factories also increased its range. During the war, windows were ordered to remain open with the volume turned up so the radio could be heard by as many people as possible. Many Republican tanks were even equipped with a radio.

One of the first and most important radio stations in Spain at this time was Unión Radio, founded in 1924 by the communications impresario Ricardo Urgoiti Somovilla (1900-1979). The Urgoiti family business also had dealings in other areas of Spanish cultures, such as film production and the press. In the space of just a few years, Unión Radio established a network covering most of the country, from Seville to San Sebastián, in addition to Madrid and Barcelona. Located in the heart of Republican Madrid, in what is now its iconic Gran Vía, at the beginning of the war Unión Radio Madrid boasted the biggest audience in Spain, making it a prime target for the Francoist bombardments. In early 1937, the station transferred its headquarters to safer ground in the basement of the daily newspaper ABC, in the Calle Serrano, moving to a quieter location, a villa in the C. Martínez de la Rosa in March. Much of the music heard in the capital during the war emanated from these studios. The station proudly claimed that no music by fascist composers had been broadcast since the beginning of the uprising.

Music was a vital part of Unión Radio Madrid from its inception. The station’s repertoire mainly consisted of reproductions from its vast record collection and classical chamber music, either performed live in the studio or retransmitted from nearby locations. From 1925 to 1929, it regularly broadcast live chamber music performed by its resident quintet: José María Franco (piano), Julio Francés (violin), José R. Outumuro (violin), Conrado del Campo (viola) and Juan Ruiz Casaux (cello), who performed several times a week. In 1931, after the declaration of the Second Republic, a new sextet was formed, performing daily, consisting of Rafael Martínez (violin; concertino of the Orquesta Filarmónica de Madrid), Luis Antón (second violin), Pedro Meroño (viola), Juan Gibert (cello), Lucio González (double bass) and Enrique Aroca (piano). During the first year of war, the sextet’s performed several times a day, before political information and communication took priority and the presentation of live music dwindled. Controlled by a Workers’ Committee, consisting of members from Spain’s two largest trade unions: three from the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) and two from the Confederación Nacional de Trabajadores (CNT), Unión Radio Madrid was instrumental in promoting the work of the Communist agitation organisation Altavoz del Frente.

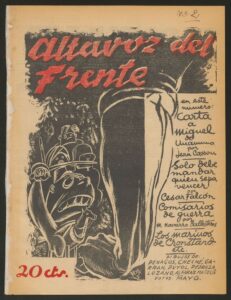

Altavoz del Frente and political songs

Founded in August 1936 by the Peruvian-born Communist writer and politician César Falcón (1892-1970), Altavoz used various forms of cultural expression to create political unrest and resistance to the fascist rebellion. It was perhaps best known for its emblematic armored trucks equipped with large, powerful speakers. By November 1936, Altavoz boasted as many as twenty of the iconic trucks, each equipped with the latest technology that the American Student Union had helped to fit. At the front, the trucks projected cinema and broadcast revolutionary music and Republican songs that could be heard up to 25 km away. The organization consisted of various sections, each run by an expert in the field, except for Radio, which was controlled by a Commission consisting of members from all the other sections. The Music section—with strong links to the Radio—included a large group of prominent Republican composers and critics including Salvador Bacarisse (the station’s artistic director since 1926), Rodolfo Halffter, Adolfo Salazar, and Óscar Esplá. It was presided over by the young composition student Carlos Palacio (1911-1997), best known as the composer of the Himno de las Brigadas Internacionales (1936).

Founded in August 1936 by the Peruvian-born Communist writer and politician César Falcón (1892-1970), Altavoz used various forms of cultural expression to create political unrest and resistance to the fascist rebellion. It was perhaps best known for its emblematic armored trucks equipped with large, powerful speakers. By November 1936, Altavoz boasted as many as twenty of the iconic trucks, each equipped with the latest technology that the American Student Union had helped to fit. At the front, the trucks projected cinema and broadcast revolutionary music and Republican songs that could be heard up to 25 km away. The organization consisted of various sections, each run by an expert in the field, except for Radio, which was controlled by a Commission consisting of members from all the other sections. The Music section—with strong links to the Radio—included a large group of prominent Republican composers and critics including Salvador Bacarisse (the station’s artistic director since 1926), Rodolfo Halffter, Adolfo Salazar, and Óscar Esplá. It was presided over by the young composition student Carlos Palacio (1911-1997), best known as the composer of the Himno de las Brigadas Internacionales (1936).

In August 1936, the Communist party instructed Palacio to set a book of poems about the war by the popular Madrilenian poet Luis de Tapia to music. He approached a small group of composers in the capital (Bacarisse, R. Halffter, José Castro Escudero, José Moreno Gans, Rafael Espinosa, and Enrique Casal Chapí) to each choose a poem. Many were members of Altavoz themselves and would go on to form part of the Consejo Central de la Música the following year. The last remaining text fell to Palacio himself and went on to become the most popular of all: Compañías de Acero, often considered the “Spanish Marseillaise”.

One of the most important aspects of the radio was its use as a vehicle for the popularization of popular political songs and anthems that were broadcast day and night. Listeners in Madrid were introduced to the musical versions of Tapia’s poems, as well as other revolutionary songs, by tuning into the radio program of the same name, “Altavoz del Frente,” Palacio hosted on Unión Radio. The fifteen-minute program, broadcast every night at 9:00 p.m. from 14 September 1936, benefitted from a significant budget and provided political and cultural information, poetry, and music. Every night “Altavoz del Frente” opened with Palacio’s harmonization of a melody from a scene from the Soviet film The Sailors of Kronstadt/We are from Kronstadt directed by Efim Dzigan (1898-1981) and ended with The Internationale. In between, there were live performances of the songs set to Tapia’s poems. Other songs broadcast during the program included Manuel Lazareno’s “No pasarán”, Joven Guardia (La chant des jeunes gardes – the official anthem of the Spanish Communist Youth Organisation since its foundation in 1921), and Hans Eisler’s famous “Comintern” anthem. Given Altavoz’s Communist affiliation, it is also significant to note the number of popular Soviet and Russian songs, performed in Spanish translations, as well as short orchestral excerpts by Russian composers—all dances—that were presented during the program’s early weeks.

“Altavoz del Frente” was undoubtedly one of the most interesting and important radio programs of the Civil War period on either side, as well as one of the most successful of the Republic. But the station provided a platform for other musical events, all tightly bound up with the Republican cause. There were live broadcasts of theatre that included varietés (vaudeville), retransmissions of operettas, and political rallies incorporating band and choral music in a bid to promote a strong and united front, and festivales, benefit concerts organized to raise money for the wounded and spread the anti-fascist message. These concerts featured some of the most prominent Spanish and foreign musicians, groups, and artists, perhaps none better known than the singer, actor, and political activist Paul Robeson (1898-1976).

On 27 January 1938, the world-famous bass-baritone was invited to give a concert at the studios of Unión Radio Madrid that was retransmitted by all the stations in the Republican zone as well as to Latin America. Accompanying Robeson over the airways were two of the performers who were most active in Madrid during the war: the soprano Ángeles Ottein—responsible for the organization of a whole Spanish Opera Season at the Teatro de la Zarzuela in mid-1937—and the violinist Enrique Iniesta. As reported in La Vanguardia (Barcelona), Robeson presented his versions of the songs “How Long?” and “Native Land,” among others, which he dedicated to the Spanish anti-fascists and workers. To complete the concert, Iniesta was accompanied at the piano by the composer Evaristo Fernández Blanco in Schubert’s Rondo for violin and piano, D 895 (published as his Op. 70) and a transcription of Falla’s “Spanish Dance No. 1” from La vida breve. Ottein performed a vocal arrangement of Granados’ popular Danza española No. 5 with Carmen Barea at the piano, as well as other popular songs including El molinero by the fallen Antonio José, assassinated by the Nationalists in Burgos in October 1936.

Chamber music for the people

The power of radio and music to promote and support the anti-fascist struggle in Civil War Spain is particularly apparent in two chamber-music concerts broadcast on Unión Radio Madrid in September 1938, both involving members of the station’s sextet. The first concert was part of a series of lectures organized by the Delegación de Propaganda and the Alianza de Intelectuales Antifascistas. Rafael Martínez (second violin) and Pedro Meroño (cello) joined forces with the prominent Republican musicians Juan Palau (viola), Carlos Baena (piano), and Jesús García Leoz (first violin and commentaries), in a program exclusively consisting of Spanish trios, string quartets and quintets from the 18th to the 20th centuries. Works by Soler, Arriaga, Chapí, Del Campo, Fernández Blanco, Bacarisse and García Leoz all helped to foment a sense of collective patriotic pride and nationalism in the audience.

A second chamber-music concert was organized by the Delegación at its headquarters a week later, on 22 September 1938. Once again, it was held late at night to accommodate the international radio audience. The concert featured four of the five precious Stradivarius instruments that were originally presented to King Philip V of Spain in 1700 and thereafter formed part of the Patrimonio de la República (now Patrimonio Nacional). The “royal quartet”—as it had been dubbed—consisting of two violins (one large and one small), a viola, and a cello, was transported through the streets of war-torn Madrid to the headquarters of the Delegación. A combination of current and former members of the Unión Radio quintet/sextet were involved: Julio Francés (violin); Pedro Meroño (violin and viola); Juan Ruiz Casaux (cello), together with Enrique Iniesta (violin) and Andrés Moro (piano). The program consisted of works by Pleyel, Viotti, Fiocco, J. S. Bach, Schubert and Rolla. This was the first time that the Stradivarius instruments were heard outside the confines of the palace for the wider population to enjoy.

Not only did radio transmit the drama of war in real-time in Madrid, but it entertained and boosted morale among both the population at large and the soldiers fighting in the trenches. It provided the perfect platform for the repeated broadcasting of political songs and anthems to vast local and foreign audiences, helping to forge and maintain a united anti-fascist spirit. At the same time, the radio was suited to more intimate musical genres, including chamber music, which often accompanied political and propagandistic speeches. Whether performed live in the studios of Unión Radio or retransmitted from the Delegación de Propaganda y Prensa in Madrid to the whole country and even the world, such endeavors helped to ensure that access to art music was no longer the privilege of an elite few. The radio’s close and constant reliance on music during the Spanish Civil War only heightened its potential as a tool for the mass dissemination of Republican propaganda and the democratization of art and culture.

Dr Yolanda F. Acker is Visiting Fellow at the Research School of Humanities and the Arts, Australian National University (ANU).