Book Review: Isa Reyes’ Escape

Dorian L. (Dusty) Nicol. “Miss Spain in Exile”: Isa Reyes’ Escape from the Spanish Civil War. Eastbourne and Chicago: Sussex Academic Press, 2021. 240pp.

Dorian L. (Dusty) Nicol. “Miss Spain in Exile”: Isa Reyes’ Escape from the Spanish Civil War. Eastbourne and Chicago: Sussex Academic Press, 2021. 240pp.

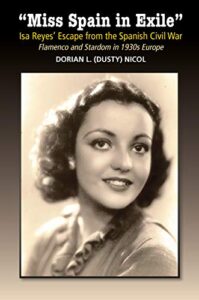

The photograph on the cover of “Miss Spain in Exile” is a carefully backlit, immaculately coiffed, sepia-toned publicity shot that exudes a certain type of mid-twentieth century glamor. The adventures of Isa Reyes in the 1930s—traipsing through louche nightclubs on the French Riviera, representing war-torn Spain at the 1938 Miss Europe contest, being propositioned by Benito Mussolini’s son-in-law—are equally as glossy as that photo and almost demand to be made into a movie (preferably filmed around 1942 in luminous black-and-white). So, what on earth are the memoirs of a now-obscure nightclub dancer doing as part of the Cañada Blanch Studies on Contemporary Spain? With an introduction by the eminent historian Paul Preston, no less?

As the title suggests, this is a memoir of a Republican refugee from the Spanish Civil War. As Preston points out, Isa Reyes’ experience of exile does not fit the traditional refugee narrative. Born Conchita Boncells de los Reyes, Isa (her eventual stage name) grew up so ensconced in bourgeois society that her mother’s most damning epithet was the term “vulgar.” Although her father’s substantial law practice allowed them to live in the comfort of a toney neighborhood near Madrid’s Parque del Retiro, politically he was inclined towards socialism. This tension between bourgeois propriety and political idealism drives the most fascinating part of Reyes’ story, its dramatic opening. Isa, her father, and her sister were vacationing in a mountain village in Ávila when civil war erupted in July 1936. As the war shifted from an abstraction heard over radio news to lived experience, Isa discovered that her socialist father was helping local priests and landowners escape from Republican-controlled territory. This episode proved key to her burgeoning political awareness. Despite her privileged background and her growing fame as a performer, after fleeing Spain for the relative safety of Paris, Isa Reyes would experience the gathering political maelstrom not from a position of privilege, but from the standpoint of an exile.

It has clearly been a labor of love for Dorian Nicol to prepare his mother’s story for publication. Nicol has “adapted” (to use his word) his mother’s unpublished and unfinished memoirs, written shortly before her death in 1991. To help place Isa’s activities in the context of contemporaneous historical events, he has added some content to the memoir, including historical background before each chapter and some short epilogues that note personal intersections with his mother’s story. Those looking for the traditional academic apparatus of explanatory notes or details of editorial intervention in the text will be disappointed, and occasionally this does the narrative a disservice. It is something of a surprise to figure out that the husband of Isa’s Aunt Encarna, who had essentially abandoned his family, was actually the journalist José María Carretero. Under the pen name “El Caballero Audaz” he was a significant propagandist for the Nationalists, disguising himself in order to remain in Republican Madrid and spread disinformation. As it turns out, Isa Reyes was surrounded by people antagonistic to Republican ideals. Nevertheless, Nicol’s work is clearly a labor of love, and it would be churlish to dwell on this book’s limitations when the story it presents is so compelling.

It is commonplace to point out that the Spanish Civil War frequently tore families apart, but Reyes’ memoir shows how families lived with seemingly unbridgeable political divides. Aunt Encarna and Isa’s cousin Alma, who took in the refugees, were sympathetic to Franco, if not outright supporters of the Nationalist cause. At first, the need to maintain a respectable Parisian address would force the women to band together. The necessity of earning a living is how Isa ended up in show business, first as a model and then in a flamenco act with her cousin Alma. But as Europe inched closer to war in the late 1930s and as “Alma and Isa” became more successful, Isa would be put into situations normally untenable for a Republican refugee—including being booked for a performance in Berlin in 1939 to celebrate Adolf Hitler’s 50th birthday. The attempt to bridge the divide between the two Spains is also at the center of the event that gives the book its title. Selected by Le Monde to be the Spanish representative to the 1938 Miss Europe contest, Reyes did not want to be used as a reason to enflame political passions, especially because her father was serving in the Republican government. While all the other contestants appeared carrying their national flags, Isa appeared with a white banner emblazoned only with “España” in gold thread. Politically it was a brilliant stratagem, highlighting her position as an exile without formally declaring a side in the conflict.

It is this duality that gives the story of Isa Reyes—a Republican refugee with wide access to Europe’s exclusive social circles—such interest and piquancy. As she witnesses the ending of an era and a social order that had dominated Europe for over a century, her memoirs do more than capture the faded glamour of those twilight years of the 1930s—especially in these unsettling times where our own political and social systems are under so much strain. One of the most memorable episodes in the book is Reyes’ encounter with an aging cavalry officer while on tour in Poland. His discussion of their mutual love for the music of Chopin leads to this observation: “the Spanish people and the Polish people understand each other … we are both a romantic and a cultured people who understand chivalry and appreciate the beautiful things in life. I hope our people will prove adequate for the modern age, which I fear does not attach so much importance to those things.”

In the twilight years before the Second World War, the story of Isa Reyes demonstrates that the issue was not that the Spanish people proved inadequate for the twentieth century. It was the modern age that failed the Spanish people, and the Spanish Republican exiles in particular, much as the 21st century seems on the verge of failing so many the world’s marginalized peoples today.

Clinton D. Young is Professor of History and Dean of the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Arkansas at Monticello. A specialist in the cultural and musical history of modern Spain, he is the author of Music Theater and Popular Nationalism in Spain, 1870-1930 (LSU Press, 2016).