Almudena Carracedo, Filmmaker: “We Try to Create a Channel for Empathy.”

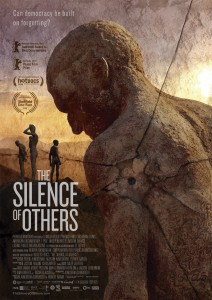

At ALBA’s 2022 online gala, I spoke with the Spanish filmmaker Almudena Carracedo, who together with Robert Bahar created The Silence of Others (2018), an award-winning documentary about memory, truth, and justice. Here is the entire conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Your film is about historical memory in Spain, but it was in principle made for PBS—that is, for an American audience—although it was screened both in the United States and in Spanish theaters. Can you tell me a little bit what the movie was about?

The Silence of Others accompanies the victims of the Franco dictatorship—some victims, obviously—for a period of six years in their journey towards justice. We follow their legal procedure in a universal jurisdiction case to obtain truth, reparation, and justice. We try to portray the obstacles, but also the successes, of the movement that has flourished in the last years.

It’s a very Spanish story. But it’s also an international story because those victims end up seeking justice in an Argentine court with an Argentine judge. Can you tell me a little bit about the reception of the movie in Spain?

You’re right—it is an international film, and that was our goal. We wanted to film to work in the US. We wanted to film to work in Europe, in Latin America, in Asia—and also in Spain. So, we had to find a way to be able to speak to a Spanish audience as well as to an international audience. At first, we thought we were going to have two different films – one for Spanish audiences and one for international audiences. And then we realized it was the same film because a big part of the Spanish audience actually didn’t know what we were talking about. What we did was to reframe everything for all audiences as a story in present and as a story about human rights. Our goal was to be able to reach that part of the audience that didn’t know anything about it in Spain, and that part of the audience in other countries that refuses to discuss issues of the past that affect us all as societies: all those ghosts that we kind of put away, hoping that they’ll go away, and they always return.

When we premiered the film in Spain, it was a complete surprise. Everyone had been telling us that no one wanted to hear about it. And what we were able to see is that there was huge interest from thousands and thousands of people. The film was in theaters for four months; 25,000 people went to see it in theaters. Mind you, this is a documentary about human rights—about Franco crimes, to be more precise. A huge part of the audience were young people. The way the film spoke to the young audiences and all those who had never discussed these things was a surprise for us. It was a surprise that we had been looking for: we had created the film hoping that it could work like that. But it was really beautiful to see that it worked. The film was helping to catalyze the conversation—along with the movement that had been going on for decades, really—among people who had never been brought to the subject, who had never understood what their history was like. A lot of these young people were very surprised. They said: “I just had no idea.” They were very angry: “They stole this history from me, my history.” If everyone knew what happened, they said, we would be in a different place. And we had to agree with that.

The story you tell in the film is one of struggle and of progress. The story doesn’t quite end in the film. It continues after the film is over—it continues today—but it’s a story of slow but steady progress, step by step, little victories and setbacks, but then followed by more victories. What you tell now about the reception in Spain seems also a story of progress, of enlightenment. People are finding things out, learning; they’re angry about what they didn’t know before—but now they know. At the same time, the far right in Spain has been trying to stop this progress or to even to revert it. The advances made by the memory movement are being literally turned back in those areas of the country where the far right is in government or supports the government, as in Andalusia or Castilla y León. How do you see the relationship between this progress that your film narrates—and the progress it achieves in the real world through its reception—and this effort to stop or revert that progress?

I’ll tell you an anecdote. When we premiered the film in Berlin, someone in the audience said: “at least in Spain, you don’t have a far right.” This was February 2018, a few months before Vox won its first seats in the Andalusian Parliament. We replied: no, the far right does exist in Spain, although they may not raise their hands in the fascist salute. A few months later, we saw that the far right was starting to be more visible, and to be very blatant about their demands. I’m not an expert, obviously, but I see those demands as a response to all the advances that we are able to gain in areas like civil liberties and women’s rights—and in historical memory. All these hard-won rights that improve the lives of most of us are now being contested. We see that everywhere. We saw that in the US with Trump. In fact, a lot of the strategies that the far right is using in Spain are copied from the Trump playbook.

The same is true for the laws that we see passed now at the state level in the United States prohibiting teaching US history in ways that would make white students feel “uncomfortable” or ashamed. I agree with you that the frustration that these laws express is a frustration with the progress made towards equality and toward a different view of national histories and of historical memory. A couple of days ago, a spokesperson of Vox in the Parliament of Castilla and Leon, where the far right is now in government, claimed that the Left has been using history to “divide Spaniards.” Do you feel that a project like the Silence of Others has divided Spaniards?

It’s a beautiful question because this is the part that moves me the most. On one hand, the film has provided a platform for those victims that had been made quite invisible by the media and by the culture. But it also somehow was able to connect those victims with the majority of society who didn’t understand that this issue also belonged to them. During the Q&A sessions after the screenings young people, but also not so young people have told us: “Thank you, because I always thought we had to forget. And now I understand.” So no, I don’t think the film has divided Spaniards. I think it’s the opposite. The cliché about history holds true: if you want to turn the page, you have to read it first. I feel that when we read the page, we’re able to be more comfortable with who we are.

How has the film been received in the United States, given the extreme polarization over the story of the national past? Didn’t your film come out right around the time of the Charlottesville protests in response to the attempt to remove the Confederate statue?

Yes, it was right around there. In fact, there’s a whole conversation in the film about memorialization that very much connected with American students. Some students who are deeply moved to tears because it suddenly hit them that this issue that they were looking at that was so far away was really close to them. And at the same time, I think it made them aware of their responsibility towards what’s happening in other conflicts right now in the world. The film helped spark in conversations not just in the US, but in Lebanon, in Argentina, in Colombia, in Finland. Anywhere we went to, people asked: “what about here?” For us as filmmakers it was absolutely amazing that we could reach such an international audience starting from a small story of a group people fighting for justice slowly.

This new push for patriotic history—framing the national story in an old-fashioned way as a series of feats and heroes to be proud of—seems to connect in my mind with the strong emphasis on emotions that the far right is thriving on. Everything that’s political becomes emotional becomes a reason for pride or for hatred. Your movie is also very emotional. Do you see any danger in activating emotions as related to the past, or do you think that there are two different kinds of mobilization of emotion, one of the type that your film does and the type that the far right is doing?

This new push for patriotic history—framing the national story in an old-fashioned way as a series of feats and heroes to be proud of—seems to connect in my mind with the strong emphasis on emotions that the far right is thriving on. Everything that’s political becomes emotional becomes a reason for pride or for hatred. Your movie is also very emotional. Do you see any danger in activating emotions as related to the past, or do you think that there are two different kinds of mobilization of emotion, one of the type that your film does and the type that the far right is doing?

That’s a very difficult question and I think it’s important to dig deeper into that idea of activating emotions. What we were trying to do, definitely, was to use the tools of cinema to help create human connections that yes, include emotion, but that have subtleties, surprises, and details, which can help create empathy and understanding. While the fight for transitional justice in Spain is an issue of the left, we wanted to bring the discussion back to human rights and crimes against humanity. We wanted people to stop discussing these issues as a matter of right or left. To help them walk in the shoes of someone like María Martín, who would go to the mass grave of her mother, whose body was buried under a road, to put flowers and sit there. We wanted people to look at María in the eye and to be able to have a conversation with her. Would you be able to tell María that she doesn’t have the right to bury her mother in a dignified way? We felt that by doing that, we were breaking barriers because people can come away with a nuanced emotional understanding of another person . This idea of an empathy engine also drives our other films.

This is different, I think, from what the far right is doing when they thrive on selective amnesia and national pride to mobilize their base. It is true that far-right movements mobilize through emotions as well, but, much like fascism did in the 1930s, they tap into hatred and rejection of the other (rather than empathy and conversation), they tap into frustrations and promise false solutions. By contrast, I don’t think we’re trying to provide solutions. We are just trying to create a channel for empathy, for people to understand these issues from a different perspective. We did the same thing in our previous film about undocumented immigrants. We pose a question to our viewers: “Now that you’ve come to know these people as human beings, if you could talk to them, what would you tell them?” We are not providing answers. We are posing questions.

[…] “Almudena Carracedo, Filmmaker: ‘We Try to Crete a Channel for Empathy.’” The Volunteer 39.2 (2022). Full text at The Volunteer. […]