Rescuing the Archive: A Spanish Friend of the International Brigades Remembers

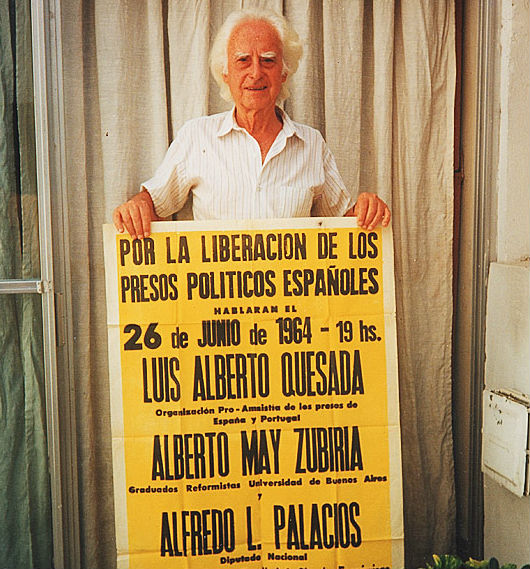

Luis Alberto Quesada holding a historic poster announcing a manifestation against Francoism in Córdoba, Argentina. SS BY 4.0.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Spanish Association of Friends of the International Brigades (AABI) worked to collect the oral histories of brigadistas and to inventory the IB’s archival legacy, which was not only geographically dispersed but often under threat. The Spanish archivist Julia Cela spent eight unforgettable years of her life on this project.

From 1998 until 2006, while working for the Association of Friends of the International Brigades (AABI), I was fortunate to meet many of the volunteers who served during the Spanish Civil War to defend the Republic. For all of them, their time in Spain was the most memorable of their lives—even if some of them had been very young when they joined the Brigades. For me personally, the years I spent traveling around the world to preserve their oral and archival memory were equally formative.

My relationship with the vets started in November 1995. The Autonomous University of Barcelona had organized a conference on Spanish Civil War exiles for whose inaugural lecture the organizers had invited Juan Marichal of Harvard University and a member of the ALBA Board of Governors, a prominent Hispanist and exile. As it happened, Marichal was also my Ph.D. advisor, and when Marichal’s health prevented him from making the trip, he sent me in his place. It changed my life.

On the morning of first day of the conference, as I waited on the platform to take the train to the university where the meeting was taking place, an elderly gentleman approached me. Speaking with a slight Argentinean accent, he told me that he was to take care of a Mexican woman, a friend of a friend, who was also attending the conference. He was convinced that woman was me. I laughed—I don’t think there is anything Mexican about me—and told him he was mistaken. He then introduced himself as Luis Alberto Quesada, the Argentine poet who, as a young man, had fought in the International Brigades. Thanks to Quesada I soon met the writer Antonina Rodrigo (whose biography about Margarita Xirgú I had read), her partner Eduardo Pons Prades, the Hispanist Zenaida Gutiérrez Vega, and other attendees of the conference—all of them Quesada’s friends. Through them, I met a group of volunteers who were organizing a tribute to the brigadistas for November 1996 to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the war. They invited me to join their association of friends of the Brigades, the AABI.

In February 1996 I went to the office that the AABI had at the time on Padilla Street in Madrid and offered to help prepare the tribute. Given that I held a degree in journalism, I thought I could be most useful as a documentalist, working in the background. Although my skills did turn out to be useful, mine became less of a background role than I’d anticipated. Working with a group of professional documentalists and librarians from the Complutense University, as well as young students of Slavic languages, we prepared dossiers on all the brigadistas who were going to participate in the tribute, while cataloguing the documents and books they sent us.

There is no need to recall the details of the 1996 tribute, in which many members of both VALB and ALBA participated. Once it was over, the AABI continued its work, preserving and disseminating the memory of the International Brigades, with documentation as one of its most important tasks. As coordinator of that effort, I traveled to several different countries to conduct interviews with brigadistas and transport the books, photographs and documents that they donated to AABI for safekeeping at the Provincial Historical Archive of Albacete.

My first trip was to New York, on the last weekend of April 1997, to attend the VALB’s annual reunion, which I’d have the privilege of joining for three consecutive years. My most vivid memory of that first US trip was a meal at the home of Bill Susman, along with the poet Marcos Ana and Ana Pérez, AABI’s president. Bill and Helen Susman lived in Long Island in a comfortable home that was exquisitely decorated but without any hint of pomposity or excessive luxury. Still, Marcos Ana asked Bill what he, a brigadista, was doing living in a big house like that. “This is how I want workers all over the world to live,” Bill replied.

Although we traveled frequently during those years to the United States and England, in both countries the documentation on the Brigades was well preserved—largely thanks to the work of the associations set up by the veterans and run by the vets, their friends and descendants. What concerned us more was the documentation in the former Eastern bloc, where the post-Communist governments showed little interest in the legacy of the International Brigades—if not did not view it with outright hostility. Often there were no well-organized associations to preserve the archive.

And so, in March 1999 we headed to Bulgaria where the family of a brigadista doctor kept a large amount of documentation of the Bulgarian volunteers, including medical advances that had barely been studied. Thanks to the young Slavic students associated with AABI, we were able to make an inventory of those documents and smuggle them out without the authorities’ knowledge.

Although the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland had better-organized archives, we found that many of these documents were no longer of interest to the governments of those countries. Thanks to IB veterans like Vodicka in Prague and Eugeniusz Szyr in Poland, we were able to establish agreements with the main archives so that copies of these documents could be sent to Albacete. In Budapest the doors of the archives were opened to us by the Hispanist Iván Harsányi. Years later, I learned that Harsányi was Sephardic Jew who as a child had been saved from the Nazis by Ángel San Briz, the Spanish diplomat who arranged for Hungarian Sephardim to be granted Spanish passports. I still regret not having had the opportunity to talk to him about that experience.

Later that year, in August, we traveled to Bucharest, in Romania, where we were hosted by the brigadista Mihail Florescu and his family, as well as the children of veteran Walter Roman, Carmen and Peter. (As President of the Senate, Peter Roman had been among those who led the overthrow of Ceaucescu.) Walter Roman and Mihail Florescu had led parallel lives: they fought in Spain, belonged to the French resistance, languished in concentration camps, and did not return to their country until the end of World War II, to occupy high positions in Romania as government ministers. Roman served as Minister of Propaganda and Florescu as Minister of Oil, from 1948 until the fall of communism in 1989.

Even in the years after, however, they wielded considerable influence. Thanks to Florescu and Peter Roman, we were not only allowed to access the national archives, but even to take the documents with us to Florescu’s home to photograph and study them. During those summer afternoons with Florescu and the Romans I learned more about European history than in all my years of study.

Among the many helping hands we encountered on our travels were often the spouses of deceased brigadistas. For these widows, who often lived in challenging financial situations, we could provide moral and monetary support—thanks especially to the generosity of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, steadfast examples of international solidarity.

Many veterans also traveled to Madrid. The same Luis Alberto Quesada whom I’d met by chance on a train platform in 1995 would visit every year. I remember one afternoon when he and Marcos Ana shared anecdotes of their time in Burgos prison—nicknamed the University of Burgos—where they both spent a large part of their youth. One anecdote, which inspired Quesada’s short story collection “La saca,” has stuck with me. Luis Alberto had been sentenced to death. Every night, the prison guards would walk down the corridor until they reached the cells of the prisoners who were to be shot that night. We can only imagine the anguish of the prisoners fearing that it was their turn, and their relief when they’d hear someone else’s cell door open. Yet every morning in the prison courtyard, the other prisoners would harp on their lives: one had been left by his wife, another had some other trivial problem. One morning, tired of hearing complaints from everyone who was not on death row, Luis Alberto appeared in the courtyard with a handwritten sign around his neck that read: No me cuentes tus problemas—”Shut up already about your problems.”

My last trip for AABI was in 2008, when I traveled to Buenos Aires to interview the only two Argentine brigadistas who were alive by then: Fanny Edelman and, once again, Luis Alberto Quesada. Quesada’s wife, Asunción Allué, had passed away shortly before and Luis Alberto was showing the first symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. We filmed the interview together with his son and grandson, both named Luis Alberto Quesada as well. At one particularly poignant moment, the old Quesada recalled that he had been arrested after he’d been betrayed by a comrade from the French Resistance, shortly after the birth of his son. In the interview, Quesada made a point of stating that he had forgiven the traitor. “Well,” added his son, with tears in his eyes, “I have not.”

Luis Alberto Quesada—who in 1963, like a rock star, had filled the Luna Park Stadium in Buenos Aires for a poetry recital alongside Marcos Ana, recently released from a Francoist prison—passed away in December 2015. Marcos Ana died 11 months later.

Julia Rodríguez Cela is a Professor of Communication at the Universidad Complutense in Madrid.