Living Memorials: Reenacting Spanish Civil War in 2021

A growing number of dedicated living historians are choosing to portray the Spanish Civil War at public history events. Although they are as diverse as the Brigadistas they portray, they are united in their passion for history and desire to inspire people to learn more about the conflict.

“We cannot simply treat the past as a playground without respecting that it was often a very harsh reality to its people,” Lorraine Scripture says. She is one of the growing number of dedicated living historians portraying the Spanish Civil War at public history events. Like countless other living historians, she has spent many hours reading histories, biographies, and primary source documents to understand what the men and women of the International Brigades wore, carried with them into battle, ate, drank, and talked about. Indeed, she argues, the best living historians “investigate widely. They don’t just get caught up in the material details of an impression.” (Many living historians use the term “impression” to refer to the collection of uniforms, equipment, personal items, and research for a certain unit.) “They look at photographs, read diaries and letters, listen to the music of the time, read the popular books, read about the social movements. Dressing the part is only one part of interpretation.” Scripture works from home “making historical clothing on commission.” (On this issue’s cover illustration, she represents “the female correspondents who covered the war on the ground.”)

Although Spanish Civil War living historians are as diverse as the Brigadistas they portray, they are united in their passion for history and desire to inspire people to learn more about the conflict. “I believe it is important to understand why so many people were drawn to the cause and were willing to risk their lives for it,” Scripture told me. “I once told a friend that in a way we are a living memorial to them, and it is our duty to do it with care and respect. I am fortunate that I work with so many talented people who do take that responsibility very seriously.”

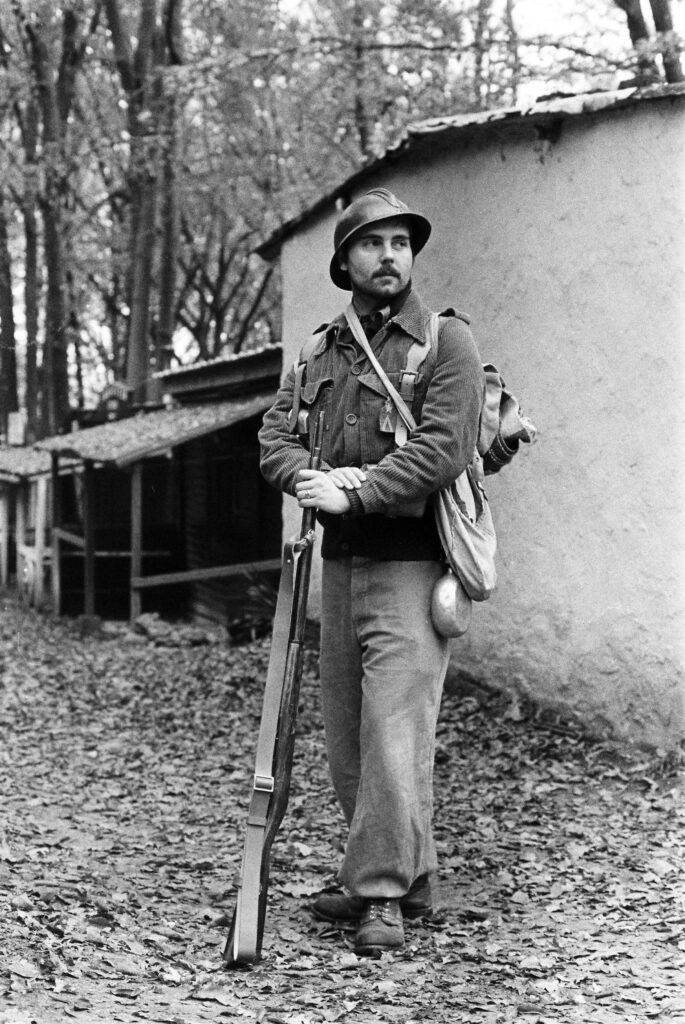

Despite the Spanish Civil War’s relative historical obscurity compared to the US Civil War or World War II, many young people are drawn to the conflict for personal reasons. Samuel Levitt, 26, tells me he has “always loved studying and talking about history.” His participation in living history events began as a 10-year-old drummer at US Civil War reenactments in New England. But when he learned about his family’s Jewish roots and their active participation in the American Labor Movement in the 20th century, he was drawn to the Spanish Civil War. In 2016, he participated in a reenactment at Jarama. “There were 4 or 5 Brits and Americans portraying the International Column,” he told me. “Spaniards were really impressed that people cared about their history outside of Spain. It was pretty powerful. The experience inspired me to improve my impression by reading up on the war.” He believes that people can learn a lot at a good public event: “I don’t remember my AP history class, or most of my classes in modern history, talking about Americans going to Spain.” Public events like reenactments, on the other hand, can help “people understand the complexities of America before World War II and the different social movements.” After receiving his MA in History at University College Dublin, Levitt moved to France where he formed “‘Le Brigadiste:’ Reconstitution GCE,” an International Brigades living history group. Above, Levitt portrays a Lincoln returning from the trenches at Jarama at an event in Paris.

Hugh Goffinet, a 19-year-old student at Howard University who won ALBA’s George Watt Award in 2020, was drawn to the history of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion after the 2015 Dylan Roof shooting and the 2016 election of Donald Trump. Uncomfortable with the rhetoric and behavior of certain members of the American Civil War reenacting community, a friend suggested that Goffinet explore Spanish Civil War living history. As he researched the impression, he quickly found himself fascinated by the Lincolns, in particular the unit’s racial integration. “There’s a lot of problematic things about the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, and the people in it, but they were progressive for the 1930s.” Living history, he tells me, “is a good teaching tool. People always love to say ‘everyone was racist back then’ as a way of excusing the politics of that era. The Lincolns challenge that narrative. They were open to eating side-by-side with African Americans, fighting with them, living in the same housing. That’s something that people can really take away from the story of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.”

Portraying a member of the Lincoln Battalion has had a deep personal impact on Goffinet. “The Spanish Civil War and living history community have provided a big opportunity for me to grow as a person and figure out who I am as a young African American man in 2021,” he said. “To embrace myself and be embraced by others. It’s been helpful for me as I try to uncover historical truths.” If he hadn’t learned the Lincolns, he told me, “I wouldn’t have won ALBA’s George Watt Award or known how to conduct historical research through the hobby.”

Mike Santana is a 28-year-old graduate student in History at Kansas State University working on a dissertation comparing American and Spanish counterinsurgencies in Cuba and the Caribbean. His interest in portraying the Spanish Civil War, he said, “really grew from wanting to understand how political polarization works, and how people are caught in the middle.” Santana believes that both living historians and the public need to understand the conflict from as many sides as possible and “get into the mentality” of the combatants: “The way I pitch it and draw a crowd at events is to talk about the war as a story of polarization. I recently had a tough question at an event at the Topeka National Guard Museum: ‘What side of the war would you have been on?’ I pointed to the map. ‘For many Spaniards, they really didn’t have much of a choice. It boiled down to where you fell when the battle lines were drawn. The reality on the ground is what I really want to show. I want to explain the courage of everyone. Courage needs to be honored, even if you don’t like what they’re fighting for.”

Reid Palmer works as a Living Historian for the Calvin H. Coolidge Medal of Honor Heritage Center and a Technical Writer for a medical device company. He also writes and produces short videos about the lived experience of twentieth-century wars on his website TheSmileyGI.com. In 2012, he won ALBA’s George Watt Award in the undergraduate category in 2012.