Faces of ALBA: The Junas Family

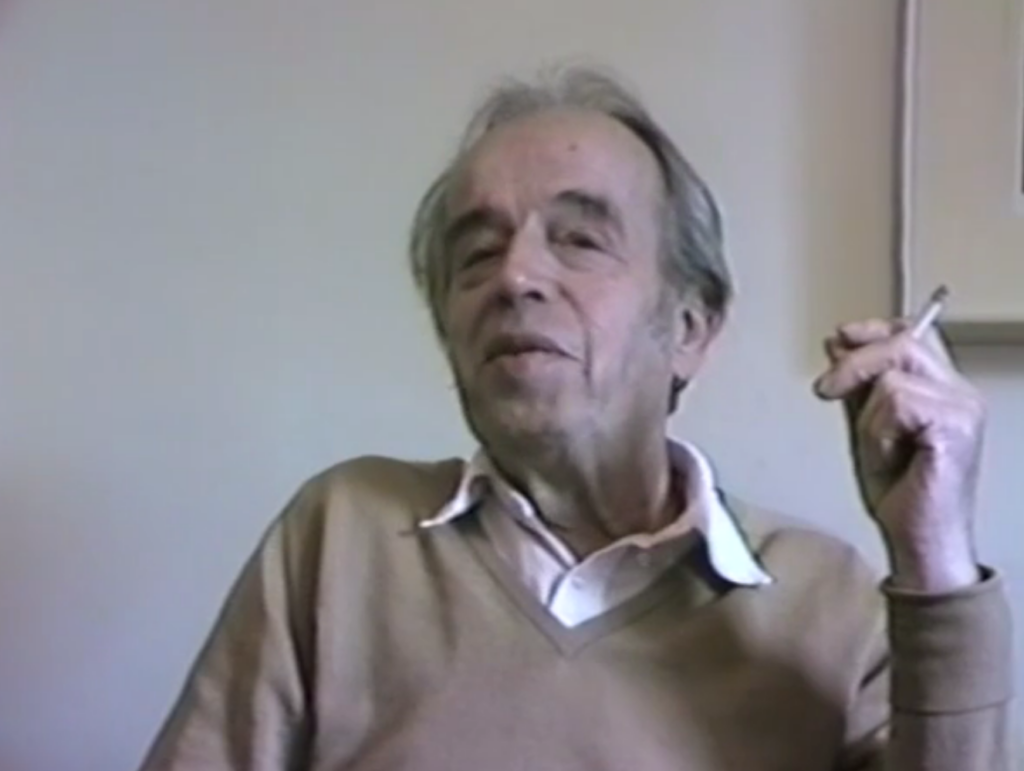

Like most veterans of the Lincoln Brigade, the experience of fighting in Spain shaped the rest of the lives of Stanley Junas and his family.

Stanley Junas volunteered in 1937, a few months after his twenty-first birthday because he was passionate about the fight against fascism and was a member of the Communist Party. After boarding a ship to England, he traversed France and crossed the Pyrenees into Spain, where he arrived in January 1938. Marching around parade grounds during his rudimentary training, he ran into a childhood friend from New Jersey whose face dropped when he saw Stan, whom he feared he would soon become another casualty of the war. But Stan survived: he fought in Belchite, drove an ambulance, fell back to the Ebro River, and left Spain after marching in the October 1938 farewell parade to honor the International Brigades in Barcelona.

He returned home a changed man—still involved in the Communist Party, but rarely speaking about his time in Spain. On May Day 1939 he married Rose Laniado, whom he had met in the fur dying trade in the Lower East Side. Rose came from a religious Jewish family from Brooklyn but took a more secular path. She had been making wigs for Shirley Temple dolls and was also active in leftist politics.

Stan took odd jobs in mechanics where he tried to learn on the job, got fired, and took up a new job. After returning from conscription in World War II, Rose’s extended family invited them to move to Grand Rapids, Michigan to work in the family business. There they raised three children—Joan, Allen, and Daniel—and tried to fit in. Stan changed the Lithuanian family name from Matejunas to Junas, while Rose, who had gone by the nickname Lanni, would later change her name to Lani.

For the Junas children, the Spanish Civil War was a silent force for many years. While Stan remained a believer in the Soviet Union, he was no longer actively involved in the Communist Party. In conservative western Michigan, even receiving Communist literature in the mail was cause for trouble. Once the mail carrier told the neighbors about their mail, their children were no longer allowed to play with the Junas children. The family was still political, especially so after the stifling 1950s turned to the more permissive 1960s. They were involved in the civil rights movement and staged an organizing event for the anti-Vietnam movement. Later, Stan became active in the ACLU and the social services of the Jewish community.

It was only when he grew older and when his youngest child Daniel, now a teenager, pressed him, that his father began to talk about his experiences in Spain. In several conversations with Daniel and in subsequent formal interviews, Stanley filled in details of his time in Spain. Stanley saw his first combat in Belchite, soon after he arrived at the front, and the trauma of that battle would haunt him. Faced against a massive approaching army, his unit was forced into a chaotic retreat. Many of his comrades were killed. In the nearby town of Híjar Stan saw casualties that, in his son’s words, “scarred his soul.” Stan’s unit reorganized; someone noticed that he had “mechanical aptitudes” and asked him to serve as an ambulance driver, which he was happy to do. He remained in danger, however. Daniel recalls his father recounting a story about a bomb exploding just in front of his ambulance. If he had been driving just a little faster, he would have been blown up. He also told Daniel about the maddening boredom of war punctuated by frantic moments of combat, when Stan, like the rest of the soldiers, was both brave and scared out of his mind, running in circles to try to escape falling bombs. Mostly, though, his father told him about why he volunteered to go to Spain—a point that was even more poignant as the family discussed what Daniel should do about registering for the draft for what they saw as the senseless war in Vietnam.

After the family moved to the Bay area, Stan reconnected with the community of veterans, especially his old comrade Donald MacLeod. They worked together in the Bay Area making audio tapes of local vets. Stan attended annual dinners, joined their protests, and became more active and vocal in politics.

In 1986, Daniel received a call from his father asking if he would join him on a trip to Spain for the ceremonies marking the fiftieth anniversary of the war. In Spain, they retraced Stanley’s steps, accompanied by an interested Chinese journalist. They drove to Belchite and Híjar— passing the battle ground where Stan and his comrades fled the fascists—and drove down the same roads that Stan maneuvered as an ambulance driver.

The Spanish Civil War impressed upon Stan’s children the importance of fighting for social justice. His daughter Joan has been active in the fight for women’s rights. Daniel researched the far right and saw his work as anti-fascist. In his final years, Stan suffered from Alzheimer’s. MacLeod and Steve Nelson visited him at his home in the Bay area. By that point, his memory was gone but as the two men got back in their car, they saw Stan standing in the doorway saluting his fellow soldiers.

Three years after his father’s death, Daniel returned to Belchite. With Solidarity Forever playing in the background, he scattered his father’s ashes at the place that had made his father who he was and shaped the lives of the Junas family.

This article is based on interviews with Joan Fisch and Daniel Junas. Aaron Retish, ALBA’s Treasurer, teaches at Wayne State University.