In Memoriam: Edward Asner (1929-2021)

The actor Ed Asner, who passed away in August, was a tireless activist and a faithful friend of the Veterans of the Lincoln Brigade.

On Ed Asner’s first day in office as president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), in 1981, the executive director handed him the ceremonial President’s gavel that Charlton Heston, who had held the position from 1965 to 1971, had left for his successors. Asner, irate, uttered an expletive and threw it across the room, telling the director to get rid of the thing. Heston was close to actor-turned-president Ronald Reagan, who’d won the 1980 election. Later, Heston would become a spokesman for the National Rifle Association and a vocal supporter of anti-union legislation. “He and Asner hated each other’s guts,” Richard Masur, Asner’s longtime friend and SAG President from 1995 to 1999, told me.

Asner, who died in August, had been approached to run for the SAG presidency following his central role in the 94-day actors’ strike a year earlier. “By then, Ed was a national television personality. He was one of the best-known faces on the picket line,” Masur recalls. “Although until that moment he had not been very involved in the union and didn’t know much about its governance, he was a very decent president.” “Under his leadership, the union took militant stances in defense of its own members and in solidarity with the broader labor movement,” John Nichols recalled in The Nation.

By the early 1980s, Asner was known across the world as Lou Grant, the grumpy city editor at the Los Angeles Tribune in the show of the same name—a gutsy, journalism-based drama series that had spun off from the Mary Tyler Moore Show, a sitcom with a laugh track. It was a sign of the times: American investigative journalism had bolstered its reputation as a pillar of democracy and the scourge of corrupt leaders through its establishment-shattering scoops on the My Lai massacre (1969), the Pentagon Papers (1971), and the Watergate Scandal (1972). Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman embodied this ethos in Alan Pakula’s All the President’s Men (1976); Lou Grant premiered the year following, in a portrayal of the fourth estate that was slightly less heroic but nonetheless deeply ethical and political.

The series, which ran for five years, inspired an entire generation of aspiring newspaper reporters in the United States and abroad. (I saw it as a teenager on Dutch television and it immediately made me want to go into journalism.) The show’s format, focusing on the daily lives of working urban journalists, allowed the writers to address issues ranging from environmental pollution and LGBT rights to domestic violence and capital punishment. Lou Grant won 13 Emmys, two Golden Globes, and a Peabody. Yet in 1982, CBS decided to take the show off the air for reasons that were never cleared up. While the network cited falling ratings, Asner and others always maintained that it was canned for political reasons, specifically Asner’s public profile as union leader and left-wing activist.

Asner, born in 1929 in Kansas City, Missouri to an Ashkenazi immigrant family, was a college drop-out (first journalism, then drama) who, after two years in the US Army Signal Corps, joined an improv group in New York City. A couple of off-Broadway gigs led to a career in television, including his seven-year stint in the Mary Tyler Moore Show. His success as lead in Lou Grant paved the way for a slew of more serious parts, including Captain Davies in Roots, as well as voice roles. (He was Carl Fredricksen in the 2009 cartoon comedy-drama Up.)

Asner led the Screen Actors Guild for four years, from 1981 until 1985, when he was at the height of his television fame. But his activism extended far beyond his union work. He was among the early supporters of what would later become the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), an outspoken critic of South African apartheid, and always ready to share his fame and network in support of progressive causes. Generous to a fault, he almost never declined a request for help.

During the 1980s, he became one of the most vocal critics of US foreign policy in Central America—which under Reagan took a criminal turn—and a supporter of left-wing movements in El Salvador and Nicaragua. As a cofounder and spokesperson for Medical Aid for El Salvador, in which the Lincoln vets were also involved, Asner helped raise $25,000 for humanitarian aid for victims of right-wing repression. In early 1982, he and other Hollywood stars traveled to the State Department to deliver the check. “One reporter asked Ed how he would feel if the leftists won and the people of El Salvador elected a communist government,” recalled his friend Kim Fellner, who then worked as communications director at SAG, in American Prospect. “He responded that if that was the result of a democratic election, so be it.”

“The moment the words were out of my mouth, I knew I was up shit creek,” he told Fellner over the phone. The statement immediately turned Asner into the target of right-wing fury and spilled over to the Screen Actors Guild as well. “The SAG headquarters and Ed’s home were graffitied with anti-communist obscenities,” Fellner writes, “and a beefy bodyguard accompanied Ed to radio talk shows in Miami, due to threats from militant anti-Castro Cuban exiles. Advertisers like Kimberly-Clark and Cadbury dropped their sponsorship of Lou Grant, and shortly thereafter, CBS canceled the show.”

For Masur, the episode illustrates Asner’s temperament and political tactics. “It reflected his total commitment and passion for what he believed in,” he told me, “but it also showed his difficulty acknowledging that sometimes there are limits to what one can do. When he went to DC for El Salvador, there was nothing he could have done about the fact that he would be identified as Edward Asner, President of Screen Actors Guild. But he could have decided to not go—or at least made clear that he was there as a private citizen, not as the leader of a union representing 65,000 people. The Guild is a nonpartisan organization, in part because we have the most diverse membership of any labor union on earth.”

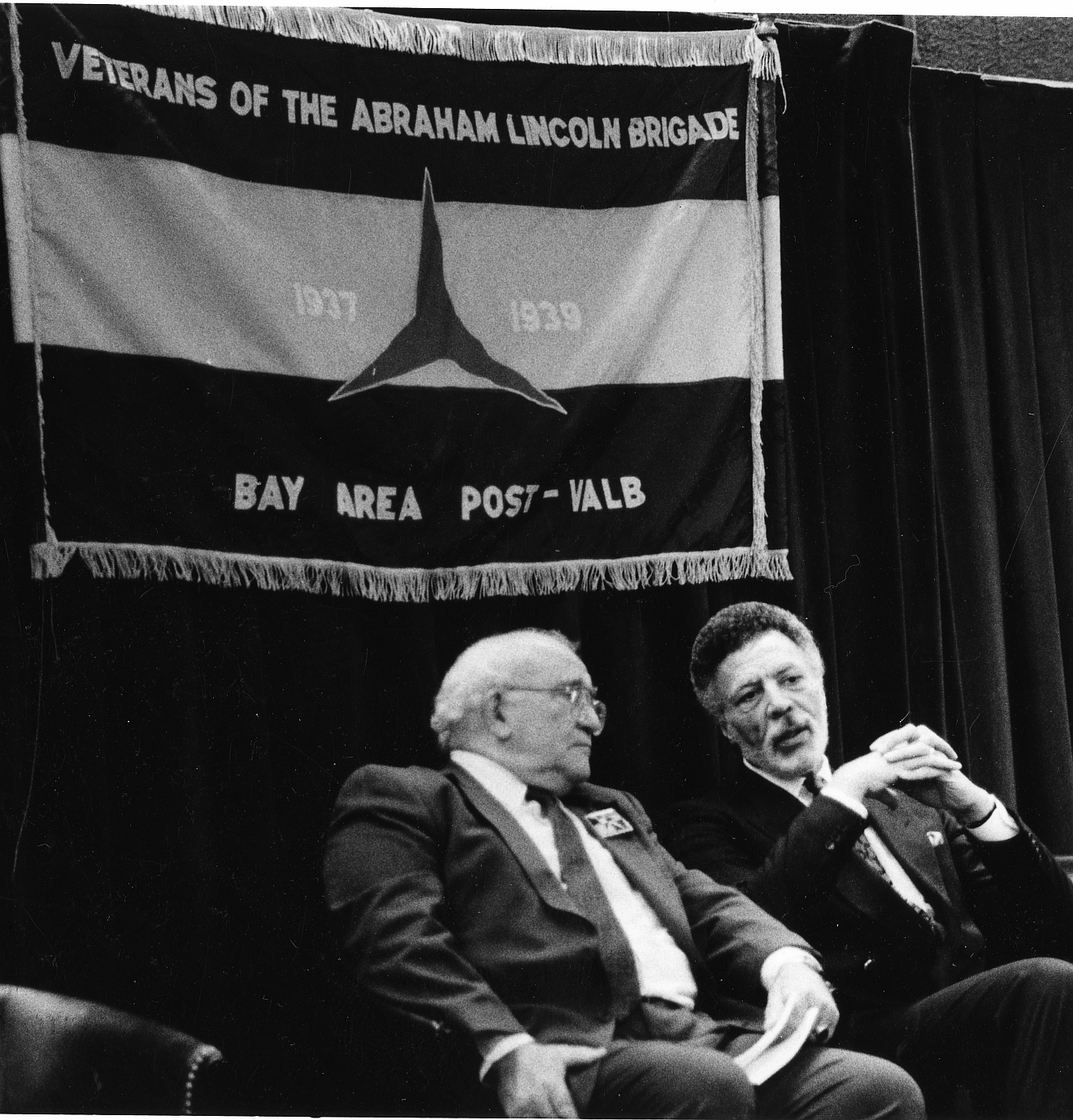

“In 1997, Ed and I worked together to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Hollywood Blacklist and the Hollywood Ten HUAC hearings,” Masur said. “As president of the union, I publicly apologized for the SAG’s involvement in the anti-Communist witch hunt. In fact, when I joined, in the early 1970s, members were still asked to sign a loyalty oath!” In the 1990s, Masur and Asner also spoke and performed at gatherings of the Veterans of the Lincoln Brigade in New York and the Bay Area, alongside other Hollywood activists like John Randolph, Ring Lardner, Jr., and Martin Sheen. Asner also spoke at the 1991 VALB anniversary dinner in Hayword, which doubled as a fundraiser for Medical Aid for El Salvador. In 1998, Asner married Cindy Gilmore, whose father, Milton Weiner, was a Lincoln veteran, and whose grandfather, Dr. Thomas Addis, had supported the Lincoln Brigade on the US home front. (The couple divorced in 2015.)

In his later years, Asner became a vocal critic of the Screen Actors Guild and opposed its merger with American Federation of Radio and Television Artists (AFTRA). “Although he and I did not always agree—and sometimes we disagreed very strongly with each other—I always respected his commitment to what he believed,” Masur said. “Two things defined Ed. Whenever you asked him to do something, he almost always said yes. That is a rare quality. And when he committed to something, he did so with absolute certainty and total passion.”

Sebastiaan Faber, who chairs ALBA’s Board of Governors, teaches at Oberlin College. This obituary appeared, in Spanish, in the magazine CTXT: Contexto y Acción in September.

[…] Full text at The Volunteer. […]