“Many Are Blissfully Unaware of the Parallels between the 1930s and Today”

The Clapton Press has been publishing a remarkable series of new and out-of-print memoirs related to the Spanish Civil War

Simon Deefholts (London, 1958) and Kathryn Phillips-Miles (Cardiff, 1958) are the driving force behind the Clapton Press, an independent publishing outfit in the United Kingdom that has been issuing “Memories of 1930s Spain,” a book series that includes both previously unpublished memoirs and new editions of books that were long out of print.

Deefholts and Phillips-Miles both studied Spanish at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth—where they met—and later at Birkbeck College, University of London. They have worked in education, translation, lexicography, and finance, and spent several years living and working in Spain. In addition to running The Clapton Press, they also continue to work as translators.

What gave you the idea to create “Memories of 1930s Spain”?

The 1930s was a critical decade not only for Spain but across Europe as a whole. The fight to defend the Republic was seen by many outside Spain as their first opportunity to take a stand against increasingly aggressive right-wing ideologues. It attracted a whole range of people from different backgrounds who provided support in a variety of ways. Many of them wrote vivid accounts of their experiences that have now been out of print for more than eighty years and can only be accessed in specialist libraries or at vast expense for collectors’ copies. Sir Peter Chalmers Mitchell’s great book My House in Málaga, for example, has been out of print since 1938. A moldy old copy will cost you close to $140 plus postage.

Tell me about the titles published so far.

We started by republishing four very different books from the period that were out of print. Boadilla is a memoir by Esmond Romilly, Winston Churchill’s nephew, who was one of the earliest volunteers to join the International Brigade. My House in Málaga, which we just mentioned, was written by an eccentric octogenarian. Mitchell stayed on in Málaga when the Civil War broke out to “look after his house and servants” and became an avowed anarchist. Elizabeth Lake, the author of Spanish Portrait, an autobiographical novel, was living in San Sebastián in 1934 when she fell in love with a Spanish artist. She returned to Madrid in 1936 to pursue her research on the Golden Age poet Góngora—as well as her love affair. Some Still Live is by F.G. Tinker, jr., a US mercenary pilot who became the Republic’s ace aviator.

After we’d published these four books, Paul Preston, who Kathryn had worked for back in the days when he was first setting up the Cañada Blanch Centre at the LSE, suggested we also look at some previously unpublished memoirs. He came up with a raft of ideas and put us in contact with other Hispanists who have generously provided introductions, afterwords, annotations, and reviews. So far, we’ve published four of these memoirs: Firing a Shot for Freedom by Frida Stewart/Knight, who drove an ambulance from the North of England to Murcia (foreword by Angela Jackson); Never More Alive by Kate Mangan, who worked in the Republican Press office (foreword by Paul Preston); The Good Comrade by Jan Kurzke, a German refugee who tramped around the south of Spain in 1934 and returned in 1936 to join the International Brigade (introduction by Richard Baxell); and The Fighter Fell in Love by James R. Jump (foreword by Paul Preston and a preface by Jack Jones).

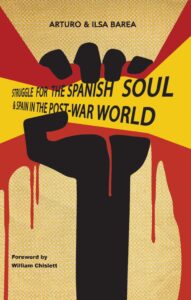

Finally, we have also continued to republish earlier works, including Struggle for the Spanish Soul & Spain in the Post War World, two essays on Spain written in the 1940s by Arturo and Ilsa Barea (foreword by William Chislett) and British Women and the Spanish Civil War, a revised version of Angela Jackson’s classic work.

It’s a remarkable enterprise. Are you aware of similar initiatives in other languages?

We’re not aware of any publisher who has such an extensive range of 1930s publications relating to Spain that are currently in print. Interestingly, until we started doing this, it was actually easier to obtain Spanish translations of some of these memoirs than the originals in English. Renacimiento in Seville, for example, has published a Spanish version of My House in Málaga. There are also Spanish versions of Boadilla, Constancia de la Mora’s In Place of Splendour, and a whole host of other memoirs from the period, such as Single to Spain by Keith Scott Watson.

Have you run into any unexpected challenges?

Copyright issues can be a real headache, especially in the USA owing to successive changes in the law. In a number of cases tracking down present-day copyright holders has proven impossible. We have had to abandon several projects, including Red Spanish Notebook by Mary Low and Juan Brea, which was first published in 1938 and republished in 1979 by City Lights, in San Francisco—but out of print since then. Some proposals we have looked at involving previously unpublished material have turned out to be just too much of an editorial challenge.

Who are you publishing these books for?

Mostly, our readers are academics, historians, and people with a special interest in the International Brigades, such as members of ALBA and the IBMT. But given the diversity of the material available, we hope to attract a wider readership over time.

How has the reception been?

So far, all the feedback has been positive. People are coming back for additional titles or purchasing several titles at once. We’ve also received a lot of encouragement from historians across the world, who see the value of bringing hard-to-access primary source materials within easy reach of a wider audience. And of course, we really appreciate the support given by publications like The Volunteer and No Pasarán, which have helped to spread the word.

The historical memory of the 1930s has been quite controversial, politically, in Spain in recent years. Is the same true for the UK?

Not really. With regard to 1930s Spain, there appears to be little awareness beyond the version of events popularized by George Orwell and Ken Loach. Many seem blissfully unaware of the parallels between some of the politics of 1930s Europe and features of present-day politics in the UK.

What’s the best title from the series to start with?

Never More Alive by Kate Mangan. To quote Paul Preston, it is “one of the most valuable and, incidentally, purely enjoyable books about the war . . .” because of its “sheer wealth of fascinating information and insight provided in brutally honest yet beautiful prose”—not to mention Mangan’s keen observation and wry sense of humor. My House in Málaga is also a great read; it unfolds at the beginning of the war and the action takes place in a city that is familiar to many.

What’s in the pipeline?

In July we are republishing In Place of Splendour by Constancia de la Mora, who headed up the Republican Press Office. This is a really engaging and informative memoir that has been out of print in English for eighty years. Our new edition will have an introduction by Constancia’s biographer, Soledad Fox Maura. And then in September, we’ll be launching the first-ever edition of Wild Green Oranges, a semi-autobiographical novel by Bob Baldock, who as a young man was one of the only US citizens to go out to Cuba and fight alongside Castro, in 1958. It’s a fascinating read!