Jan Kurzke’s Spanish Civil War Memoir: A Soldier’s Tale

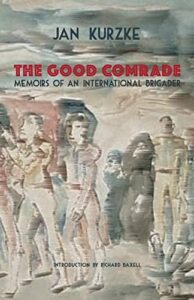

Kurzke’s memoir The Good Comrade was published this past May by the Clapton Press, after having been tucked away for years, known only to a small number of specialist historians. In this new introduction to the book, Richard Baxell explains why it’s so valuable.

In November 1936, during the first few months of the Spanish Civil War, a handful of English students were holed up in the Department of Philosophy and Letters, in Madrid’s University City. They were part of a desperate and last-ditch effort by the Republican government’s forces to hold back Franco’s Nationalist troops who were advancing ominously on the Spanish capital. The group of students were reduced to taking pot-shots at the occupants of the adjacent buildings, ‘firing from behind barricades of philosophy books.’ The piles of dense volumes of Indian metaphysics and early nineteenth-century German philosophy, they discovered, gave highly effective protection against enemy small arms fire. Given that the Republican government had made vigorous efforts to promote education and raise Spain’s shameful literacy levels, while the leader of Franco’s Foreign Legion had been accused of yelling ‘long live death’ and ‘death to intellectuals’, it’s difficult not to see the skirmish as a metaphor for a much wider struggle.

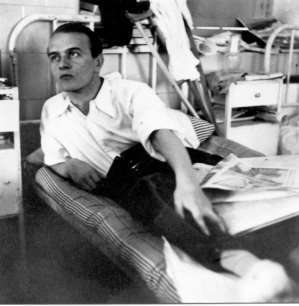

The group of young students were members of the now-legendary International Brigades, made up of volunteers from around the world who were determined to fight for the Spanish government against the forces of General Franco and his German and Italian backers. The majority were from Britain, though one was from Germany, a refugee from the Nazi regime. He was, wrote one of his fellow volunteers, ‘a very handsome young man, with aristocratic looks and manners . . . [a] very quiet, cultured chap . . . and a talented artist.’ His name was Jan Kurzke.

Born in 1905 to a German father and Danish mother, Hans Robert Kurzke, known as Jan, hailed from a modest background, leaving school at fourteen. However, having shown promise as a portrait artist, two years later he was awarded a scholarship to art school. During the 1920s under Germany’s progressive Weimar Republic, he became interested in left-wing politics and worked for a time for a Socialist newspaper. In the early 1930s, with Hitler’s Nazi Party becoming increasingly powerful and violently attacking its opponents, Kurzke prudently fled into exile, traveling through North Africa before ending up in Spain.

Kurzke’s account of his experiences in Spain, published here, was written while the civil war was still raging. It’s a common media trope to talk of ‘long-lost memoirs’ being ‘discovered’ but this is often down to journalistic license (as archivists and historians will confirm). This is not the case here either, for the typescript has resided for some time in the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. However, despite a number of previous efforts to see it published – including one by Bernard Knox, a friend of Kurzke’s from Spain, who went on to become a well-respected Professor of Hellenic Studies at Harvard – it has remained tucked away for years, read only by a small number of specialist historians.

Kurzke’s record forms roughly half of a wider memoir that was co-written with his girlfriend, the artist, model and journalist, Kate Mangan (formerly Katherine Prideaux Foster). The two accounts were originally combined into one volume, though it’s pretty clear that Kurzke always intended for his account to stand alone. Now disentangled from each other, the two memoirs have been published separately; Jan’s under the full memoir’s original title, The Good Comrade and Kate Mangan’s as Never More Alive: Inside the Spanish Republic. While the two occasionally overlap, they are very different, both in subject matter and in tone. Kate worked in the Spanish Republic’s Press Office for a time and her account dazzles with descriptions of celebrities such as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender, Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gelhorn, Gerda Taro and Robert Capa. Kurzke’s memoir, on the other hand, is a soldier’s tale, focusing on his personal experience of combat. He frequently resorts to short, sometimes even terse, sentences, which read much like a series of diary entries, helping to create a real sense of immediacy. It’s notably anti-heroic and a generally honest appraisal, laying bare his own faults and errors, as well as those of his comrades and the Republican army itself. He has a keen eye – he was, after all, an artist – and the account is littered with well-observed descriptions of Spain, its people in the 1930s and the civil war.

While personal accounts are by their very nature subjective and not always reliable, Kurzke’s does chime with other accounts, by both contemporaries and historians. When his friend Bernard Knox first read the memoir, many years after the war, he was astonished by Kurzke’s extraordinary power of recall and the ability to bring back memories of people and events long forgotten, often capturing the particular linguistic idiosyncrasies of his comrades. He wrote with genuine admiration of Kurzke’s account of the fighting in Madrid, how he ‘catches the reality, the tone, the feel of those terrifying and exhilarating few weeks.’

Kurzke did have a distinct advantage over many other foreign commentators on the civil war, in that, having traveled extensively through the country, he spoke enough Spanish to be able to have some understanding of its history, culture and politics. This allowed him insight into areas such as the rivalries between the political factions on the Republican side that bewildered so many foreigners. Nevertheless, in contrast with some memoirs by protagonists, Kurzke does not over-labor the political lessons to be drawn. There is wry humor too, with no attempt to soft-soap the chaos and confusion that is often part and parcel of a foot soldier’s lot. His description of one morning in Madrid is typical:

The sun rose. We still marched. It was nearly eight o’clock when we reached a village. We halted and received a cup of coffee, a little brandy and a piece of bread. We waited again. Somebody said the attack was off. Somebody always says something. We told him to get stuffed.

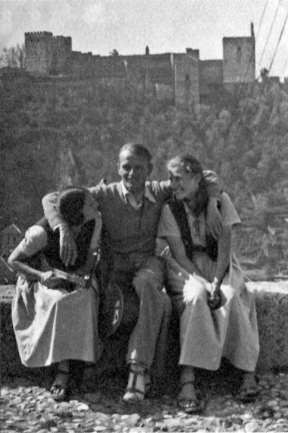

Kurzke’s memoir actually begins two years before the civil war, in 1934, as he takes leave from Barcelona, his girlfriend and most of his belongings, which had been stolen from his hotel. His colorful description of tramping from Alicante to Málaga, a trek of nearly 500km, gives a personal and poignant insight into the appalling levels of poverty and inequality in early twentieth-century Spain. Unlike the winsome Laurie Lee, Kurzke had no violin with which to charm the locals, though his ability to draw a likeness and speak English provided him with the occasional peseta. In Granada he encountered a group of busking German emigres who asked Kurzke if he would like to join them, despite his lack of musical prowess. His decision to accept was due, in no small part, to the presence of a ‘beautifully built’ young blonde. ‘I am Putz’, she informed him. The leader of the German troop, Walter, informed Kurzke that he could join them under one condition: ‘You mustn’t fall in love with her.’ Of course not, he promised.

The first section of his memoir ends, somewhat abruptly, in Granada, before picking up again in Cádiz in late summer, with the depiction of a rather dismal bullfight, where the bull, which hadn’t been killed cleanly, ‘had to be finished off with a knife.’ At this point, the narrative pauses once again. Though we don’t hear it from him, Kurzke bid a no doubt emotional farewell to the admirable Putz – who, of course, he had fallen for, and made his way to Mallorca, where he fell in with a crowd of English holidaymakers who took him back to Britain with them. At a party in London he met Kate Mangan, who was recently separated from her husband (the Irish-American writer, Sherry Mangan), and the two soon fell in love.

Early in 1936 the couple traveled to Mallorca and then on to Portugal, where they heard the dramatic news that a military coup had been launched in Spain against the democratically elected government. Jan immediately wanted to go to Spain to volunteer, but with the frontier closed, the pair were forced to linger in Portugal, reading newspaper reports of the rising with growing alarm. Both were horrified to find that a massacre of 4000 Republican defenders at Badajoz, just over the border, ‘was greeted with open rejoicing, the newspapers gloated over the massacres and boasted that the streets were running with blood.’ Kate later speculated that Jan’s loathing of Franco’s Nacionales was bolstered by seeing a propaganda film about the Spanish Foreign Legion called La Bandera. It featured an officer with one arm and an eye-patch, clearly based on the Legion’s infamous commander, General ‘long live death’ Millán Astray:

It was not that it inspired him with animosity against the men of the Legion but it made him want to lead such a life, and perhaps death, of hardship and comradeship in a cause he believed in.

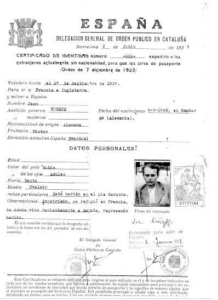

While Kate approved in principle of Jan’s wish to volunteer, she was understandably anxious about what might happen to him. However, deeply troubled by the prospect that Madrid might not be able to resist against Franco’s army, he was utterly determined to go. His desire became even more urgent when he heard of the failed Catalan attempt to capture Mallorca in mid-August and the fall of Irún in northern Spain the following month. Jan and Kate returned to London and having sensibly obtained a typhoid inoculation, Kurzke secretly set out for Spain in October.

Like the majority of volunteers who left from Britain for Spain, Kurzke made his way to Paris, where the Communist Party headquarters in La Place du Combat (now La Place du Colonel Fabien) was acting as the central recruiting point for the International Brigades. He then joined other international volunteers on a boat and was smuggled into Republican Spain:

In less than an hour we should be in Alicante. I say ‘we’ now, because I am not alone and the ship is much bigger than the one I came on before. We are six hundred men, Germans, Poles, French and English and we know what to do and where we are going.

Kurzke was one of many volunteers for the International Brigades to see the fight against Franco as part of the same struggle they had been waging throughout Europe. French Socialists, Polish exiles, Germans and Italian antifascists, all hoped that victory in Spain would be a first step towards achieving the same in their homelands: ‘oggi in Spagna domani in Italia’, wrote one Italian volunteer, ‘today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy’.

Kurzke paints a colorful picture of traveling through Republican Spain on trains that rarely increased their speed above walking pace, of railway stations bedecked with banners defiantly parading their solidarity with the Spanish Republic. Kurzke’s unpretentious prose movingly recreates the powerful emotions that many volunteers remembered, inspired by the welcoming crowds, waving flags and chanting ¡Viva la República! ¡Viva la democracia! ‘Spain had come to greet us’ he wrote proudly. His account, like those of many others, illustrates, contrary to Francoist propaganda, just how welcome these foreigners really were.

Most volunteers for the International Brigades served with their national compatriots, partly because of the common language. Kurzke, however, chose to fight alongside the group of young English volunteers he had met traveling to Spain. At this point in the war there were not yet enough English-speaking volunteers to form a battalion, so Kurzke and his comrades were assigned to a French unit, part of the 11th International Brigade. Officially called the Commune de Paris Battalion, it was known by all as the Dumont, after its popular commander, a former French army officer and long-standing Communist. The English group that Kurzke joined was led by a handsome, charismatic and brilliant former Cambridge student called John Cornford. He had originally intended to write about the conflict, but decided that ‘a journalist without a word of Spanish was just useless’ and had taken the decision to actively join the fight. Alongside Cornford was a friend of his from Cambridge, the classics scholar Bernard Knox, and a writer called John Sommerfield. Other students to join the group were a young Jewish east-ender and Archaeology undergraduate, Manny ‘Sam’ Lesser and a Rear-Admiral’s son and Edinburgh medical student, David Mackenzie. All were, like Cornford, members of the Communist Party. Despite their undeniably scholarly and bourgeois backgrounds, it would be a mistake to assume that the members of the International Brigades were mainly intellectuals. In fact, the students were a small minority and, as Kurzke describes, most were working-class, political activists:

There was Fred, twenty-nine years old from London and his inseparable friend Steve, a small cockney with a big nose and blond hair. There was Jock, a Scot, who had done a prison term for mutiny, he later rose to the rank of colonel. There was Joe, an ex-fighter from the Red Army in China. There was George, a pale, thin young man with a red beard which made him look like Christ and Pat a young Irishman.

Kurzke’s portrayals of his comrades are generally unsentimental but affectionate and occasionally reveal his dry amusement. The bewilderment of their French comrades at the two John’s precocious pipe-smoking habit and their vain attempts to mimic Jock’s impenetrable Scottish accent ‘by making strangled sounds’ provide a brief respite of comic relief. Though the group clearly seems to have formed a strong bond, Kurzke hints that they were not immune to the misunderstandings and differences that could develop between the middle-class students on one hand and the working-class activists and former soldiers on the other. As Winston Churchill’s nephew Esmond Romilly also recounts in his own memoir, Boadilla, some of the ‘old sweats’ harbored grave doubts about the younger volunteers’ lack of military experience, and were fearful that they might unwittingly put themselves or their comrades in danger.

Any doubts were unlikely to be assuaged by the standard of military instruction given in Spain. Kurzke’s experiences of a rather brief and chaotic period of training echo that of other accounts. In the International Brigades orders were usually given in the dominant language of the unit, which for the German Kurzke and his British friends, meant French:

Every morning we trained in the wood just outside the town with many Spaniards looking on. They mimicked Marcel’s ‘un, deux, un deux.’ They had every reason to be amused. When Marcel said ‘à gauche’ some went to the left, others to the right.

Uniforms were anything but uniform and the mishmash of different outfits led to the first of the International Brigades becoming portrayed as ‘the army in overalls.’

The next day we were issued with uniforms consisting of dark blue skiing pants and jackets which looked like those worn by the serenos or night watchmen. They were of thick blue cloth with black braid. They were made for smaller people and did not fit at all … our company looked a fantastic sight. The berets and the short jackets made us look like a bunch of artists from Montmartre.

The arms issued were similarly hotchpotch, consisting of numerous different makes and calibers. Many were in poor condition, some were antiquated and obsolete. Kurzke was appalled to discover that his rifle was an American Remington from the First World War. Many were even older. Kurzke’s account amply demonstrates how the western powers’ policy of non-intervention in the Spanish war, which severely limited the Republic’s opportunity to purchase arms, actually played out on the ground.

Like soldiers of time immemorial, Kurzke writes about the misery of being exhausted, hungry, thirsty, wet, and freezing cold; ‘war is bloody’ wrote George Orwell famously. The food was dreadful and stomach upsets endemic, ‘nobody slept much [and] the cold was terrible’, consequently ‘some men got colds and infected everybody else and soon most of us were coughing and spitting.’ As Kurzke and his comrades learned, though Madrid is often warm during the day, the city’s altitude means it can get surprisingly cold at night. This rather came as a distinct shock to many of the volunteers from Britain, as the correspondent for the Communist Daily Worker, Claud Cockburn, sneeringly related:

They had all got the impression they were going to sunny Spain, they’d all seen the posters. And the main source of discontent and grumbling … [was] the feeling that somehow they’d been swindled by the weather.

Understandably, many men became disenchanted and drunkenness very quickly became common, causing serious discipline problems, as Kurzke admits:

Our Jock was one of them; when he was drunk he started slugging everybody. We wanted to send him back to England but he would not go and he became a great nuisance.

It’s not difficult to understand why such pessimism was rife. In many ways, November 1936 was not so much a time of heroism and glory, as one of trepidation. Few doubted that it was a time of great peril for the Spanish Republic. Franco’s forces had effortlessly brushed aside any opposition on their advance on Madrid. Now the enemy was very much at the gates; ‘everything looked grey, dirty and hopeless,’ confessed Kurzke.

Widespread rumors that Foreign Legionaries and Moroccan Regulares had been seen moving into the western suburbs of Madrid had aroused terror and panic among the city’s population. The wholesale slaughter of the Republican defenders at Badajoz ensured that madrileños were in no doubt of their fate, should Franco’s forces prevail. And very few doubted that they would, not least the members of the Republican government, who had decamped to Valencia, leaving the city under the command of a military defense junta. Franco’s field commander, General Varela, was supremely confident that his elite force of Spanish Legionaries and Moroccan mercenaries would encounter no more resistance than they had over the previous four months. However, to the astonishment of the representatives of the world’s media, some of whom had already filed stories of the capital’s fall, the population were determined to resist. ‘Madrid will be the tomb of fascism’, declared its grimly determined defenders: ‘They Shall Not Pass!’ The battle for Madrid, the central epic of the Spanish conflict, was about to begin. ‘Spain was the heart of the fight against fascism,’ wrote a supporter of the Spanish Republicans, paraphrasing W.H. Auden’s famous poem, Spain, ‘and Madrid was the heart of the heart.’

On 7 November 1936, Kurzke was among the first of the International Brigades to arrive in the capital to take their place alongside the Spanish defenders. While many madrileños assumed that they were Russians, the 1900 volunteers were in fact mainly French, Germans and central Europeans. But, as the Madrid correspondent for the English newspaper, the News Chronicle Geoffrey Cox, reported, ‘Madrid was not worrying who these troops were. They knew that they looked like business, that they were well-armed, and that they were on their side. That was enough.’ As Arturo Barea, who worked for the Republican Foreign Ministry’s Press Office recounted in his magnificent autobiography, The Forging of a Rebel, the defending Spanish Republicans were jubilant:

Milicianos [militiamen] cheered each other and themselves in the bars, drunk with tiredness and wine, letting loose their pent-up fear and excitement in their drinking bouts before going back to their street corner and their improvised barricades. On that Sunday, the endless November the 8th, a formation of foreigners in uniform, equipped with modern arms, paraded through the centre of the town: the legendary International Column which had been training in Albacete had come to the help of Madrid. After the nights of the 6th and 7th, when Madrid had been utterly alone in its resistance, the arrival of those anti-Fascists from abroad was an incredible relief . . . We all hoped that now, through the defence of Madrid, the world would awaken to the meaning of our fight.

Despite their inexperience and lack of meaningful training, the International Brigades were nevertheless among the Republic’s best troops. Consequently Kurzke’s battalion was thrown into combat, first in the Casa de Campo, the large park to the west of Madrid, then as part of a ‘great flanking attack on the Fascist lines at Aravaca’, just to the north of the park, before moving to occupy the shell-pocked buildings of University City. His description of the devastation wrought on Madrid is depressingly familiar, no surprise given that the civil war was clearly a forerunner of what was to be unleashed across Europe, and beyond:

There was a great house with only the outer walls standing and the interior blown completely out like a piece of scenery for a film. Through the windows one could see into the empty space strewn with débris and blackened by fire. Other houses were cut in half with furniture hanging from the blackened ruins.

Kurzke’s descriptions of the frontline fighting evocatively portray the moments of terror interspersed with hours of boredom that soldiers endure, and he captures the confusion, the blunders, and the disasters that are an inevitable consequence of warfare. His account of the accidental death of the group commander, a former soldier from London called H. Fred Jones, is very moving, though just as harrowing is his description of a group of Polish volunteers who had been hit by shellfire:

They all looked strangely alike; their faces pale, waxen, yellow, their eyes dark and still with the expression of surprise and horror of the terrible moment when the shell had burst upon them. Their hair was full of sand as if they had been buried. I fumbled for a cigarette and lit one. One of the wounded was talking to me in Polish and I could not understand what he said. He looked at my cigarette and I put it in his mouth. He sucked it greedily and then died, the smoke still trickling from his mouth.

Fully aware that they were pitted against the best troops of Franco’s army, it must have seemed miraculous to Kurzke that the hastily-assembled forces defending Madrid managed to throw back Franco’s forces. Yet throw them back they did. However it was only a temporary setback for, the following month, Franco launched a new offensive, hoping to encircle the Republican capital to the north. Consequently Kurzke’s unit in the 11th International Brigade was moved up to help stem an attack on the village of Boadilla del Monte, fifteen kilometers west of Madrid.

It was to be, Bernard Knox believed, ‘the biggest offensive the Fascists had yet launched.’ Occupying a defensive position in Boadilla, the defending Republican forces quickly found themselves hopelessly outgunned and outnumbered. Kurzke’s group were forced to retreat through the village, crawling on their stomachs to avoid the murderous hail of bullets. Bernard Knox was hit in the throat and he later described eloquently how he was consumed with a furious, violent rage: ‘Why me?’ he wrote,

I was just 21 and had barely begun living my life. Why should I have to die? It was unjust. And, as I felt my whole being sliding into nothingness, I cursed. I cursed God and the world and everyone in it as the darkness fell.

Shortly afterwards, Kurzke was also wounded, briefly losing consciousness after suffering ‘a fearful blow’ to his right leg. Both Knox and Kurzke were fortunate to survive. Two days later, another small group of British and Irish volunteers, part of the German 12th International Brigade, were not so lucky. The group, of whom Churchill’s nephew Esmond Romilly was part, were virtually wiped out trying vainly to recapture the village that Kurzke and his comrades had fought so hard to defend.

Kurzke’s painful journey to hospital in Madrid and his subsequent convalescence in Murcia and Valencia comprise the final part of his memoir. His recovery was a long, slow process and reveals not just the critical lack of resources in Republican medical facilities, but also the personal toll it took on Kurzke. At one point, unable to sleep due to an agonizing pain in his damaged foot, he pleaded to be given a painkilling injection: ‘A strong one,’ he begged the nurse. ‘I don’t want to wake up any more.’

Eventually, however, Kurzke did recover and he was safely repatriated to the UK. But the story of Kurzke’s convalescence holds a puzzle that goes right to the very heart of this memoir. That is, what is missing from his account and why. Clearly, as in any first-hand account, there is much that has been left out: there’s very little on Kurzke’s life before arriving in Spain in 1934, apart from what comes out in conversations with people he meets on the road. There is also the missing period between tramping around Spain in 1934 and his return to the fight for the government two years later. Did he ever write about this time, or did he later decide to edit it out? And what about the story of his life after leaving Spain?

Yet the most significant absence from the book only becomes clear if you have read the account written by his girlfriend, Kate Mangan (and I strongly recommend that you do). She was with him in Portugal when news of the military coup began to trickle out and she travelled to Spain to find him after he volunteered. After he was wounded, she tracked him down to his hospital in Murcia, no mean feat given the chaotic nature of record-keeping in Republican hospitals. And when he was transferred to the Pasionaria hospital in Valencia in April 1937, she devotedly followed him there. She essentially nursed him back to health and almost single-handedly got him out of Spain, accompanying him on the train to Barcelona and over the frontier to Perpignan, Cerbère and Paris. And she got him back to England, despite him being essentially a stateless refugee. Yet Kurzke makes no mention of her at all.

This is problematic because, as Bernard Knox acknowledged, her glaring absence potentially raises questions about Kurzke’s reliability as a witness:

The real difficulty most readers will face is … the total exclusion in Jan’s account of Kate from his narrative – not only the meeting with him in Madrid before Boadilla which ended with the night they spent in a hotel (he substitutes a night in a hotel with a girl he picks up) but also of her many visits to him in hospital and even of her company on the train leaving Spain for France. Coupled with her very moving accounts of her efforts to trace him and her devotion to him once found it presents a real problem both morally and artistically. For one thing the reader cannot help feeling that he is capable of suppressio veri in such a vital matter, he may be also capable of suggestio falsi.

How Kate must have felt about being written out of her lover’s account is not known, but she must have been hurt. It’s hard not to agree with the words of a French fellow patient of Jan’s who remarked, ‘Il a de chance le bougre, d’avoir sa femme ici! (He’s a lucky bugger, having his wife here!) Still, perhaps she was slightly mollified to discover that other individuals had also been excised, such as the American Kitty Bowler, who visited Jan in the Palace Hotel in Madrid, and Kate’s long-term friend, the journalist Hugh Slater, who visited Kurzke in hospital in Murcia. Why Jan cut Kate out is not entirely clear, though when she tracked him down in Spain and asked why he hadn’t answered any of her letters, Kurzke told her that:

his life now was too different from anything I could imagine. He did not want to see girls or maintain any links with what to him was another world. He talked as if he were already dead.

One possible explanation for Kurzke’s equivocation might lie with his previous episode in Spain and infatuation with the beautiful young German woman, Putz. It seems highly likely that Kurzke’s decision to go to Spain was driven, in part at least, by a desire to find Putz. Certainly that was the impression gained by Bernard Knox and other comrades of Jan in Spain. In fact, in his memoir Kurzke describes meeting up with Walter (the leader of the German group of musicians) in Madrid and asking where he might find her, only to be told that she had been killed three months earlier. His poignant description of his feelings for Putz reveal an emotional numbness, even existential despair, amid the realization that all too soon he will also exist only in memories:

I felt very tired. I wanted to think of Putz, but I could not. There was a blank every time I thought of her. There was some mistake, surely, it could not be and yet I knew it was true, but something kept on saying, ‘there must be a mistake – people are often reported dead and it proves false.’ I had to find out, but when and where and how? I knew she was dead. It was no good pretending it was not so. It did not hurt much. It was unreal, like anything else in the war. A bad dream. After one wakes up, it is all over and past. What did it matter? How long is one going to live? A few days, perhaps a few weeks.

Readers, perhaps, should not be too hard on Kurzke. He was by no means the only veteran of the war in Spain to be deeply scarred by his experiences. Rose Kerrigan, wife of the senior British Political Commissar in Spain, described how she found her husband altered almost beyond recognition on his return:

There was a terrible change in him, he was quite morose and he seemed very within himself. He was really going grey and this was because he’d seen all the people who had died in Spain.

After all, Kurzke had willingly and selflessly volunteered to put his life on the line for the Spanish Republic. He was lucky to survive the war at all; many didn’t. Of almost 2500 men and women to go to Spain from Britain, one-fifth never returned. The psychological effects of combat and the death of many of those he served alongside – then known as ‘shell-shock’, but now referred to as PTSD – can be profound and enduring. Certainly Kate found him to be ‘very melancholy [and] despairing’ when he was in hospital and understood that ‘a man cannot be left alone in bed for months thinking and be the same as he was before.’

Spain provided a salutary lesson for the antifascists and supporters of the Spanish Republic, many of whom never got over their shock and heartbreak. Their feelings of desolation and despair were admirably summed up by the French writer and philosopher Albert Camus in his preface to Espagne Libre:

In Spain [my generation] learned that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own recompense.

The International Brigaders had warned that defeat in Spain would bring war not peace, yet the democracies had remained unmoved. ‘The writing on the wall would not be read, not even if it were written in flaming letters,’ raged Kurzke. It soon would be. On 1 September 1939, as Hitler’s Wehrmacht forces swept across the border into Poland, the Western powers could hardly claim that they had not been warned.

Richard Baxell is a historian & lecturer and author of Unlikely Warriors. He is the Historical Consultant for the International Brigade Memorial Trust. The Good Comrade has been published by the Clapton Press.

[…] The Good Comrade. I was very pleased to be invited to write an introduction, which has now been published on the website of ALBA, the organisation that preserves the memory of the American volunteers. It also appears […]