“Histories of the International Brigades Have Focused Too Much on Europe and North America.”

Jerónimo Boragina has published a new biographical dictionary of Argentine Volunteers in Spain

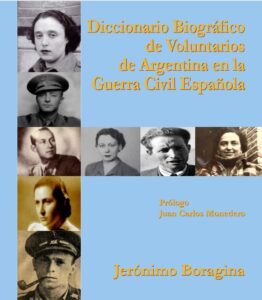

It has taken him twenty years, but the book is finally here. The Diccionario biográfico de los voluntarios de Argentina en la Guerra Civil Española (Biographical dictionary of Argentine volunteers in the Spanish Civil War), by the historian Jerónimo Boragina, has just been published in Spain by the Friends of the International Brigades (AABI).

It has taken him twenty years, but the book is finally here. The Diccionario biográfico de los voluntarios de Argentina en la Guerra Civil Española (Biographical dictionary of Argentine volunteers in the Spanish Civil War), by the historian Jerónimo Boragina, has just been published in Spain by the Friends of the International Brigades (AABI).

Boragina is the author of several books, including one on Jewish volunteers from Argentina (Voluntarios judeoargentinos en la Guerra Civil Española, 2016). He also did the research for the documentary Esos mismos hombres (Those Same Men, 2008), and currently directs the Archive of Argentine Volunteers (AVAGCE) in Mar del Plata, Argentina.

Why this book?

There are many well-known studies of the English-speaking volunteers. One of my obsessions is to overcome the Eurocentric focus that has dominated so far and to do justice to the important role played by Latin Americans and others.

What, in your mind, is the function of biographical dictionaries such as this one?

The effort to rescue the names and life trajectories of the individual men and women who helped shape history, I believe, is just as important as providing a global vision of a particular event or movement. Of course, it’s not always possible to recuperate every name and life. In the case of Argentina, my archival work has allowed me to identify some 1,100 volunteers. The dictionary contains the 962 individuals whose participation I have been able to confirm.

How many Argentines were listed in early studies, such as the classic history of the IB by Andreu Castells?

Between 90 and 100.

That’s a huge difference!

That’s right. We’ve seen something similar happen in the case of the Cuban volunteers. The most recent research suggests there were more than 1,200.

What explains the relative invisibility of the Latin American volunteers?

For one, many of them preferred to join the Spanish mixed brigades. Others were encouraged to do so by the Republican high command, which sought to camouflage the presence of foreigners with an eye to the League of Nations and the Non-Intervention Committee in London. Another reason is that many of the volunteers who left for Spain from Argentina were immigrants—the country had seen a massive influx since the late nineteenth century—who, once in Spain, joined Italian, Polish, and other battalions. Yet others ended up in militias controlled by the Anarchists or the POUM.

In your earlier book on the topic, Voluntarios de Argentina (2005), you make the case for writing “history from below,” inspired by colleagues such as Eric Hobsbawm, Raphael Samuel, or Howard Zinn.

It’s a counter-cultural way of writing history that resists professionalization and defies what was long the dominant historiography and that focused not on common people but on institutions, processes, or leading men. Methodologically, it expands its focus beyond the official archive to include oral history, socio-biography, and cultural history. In my case, this methodology was not just welcome but necessary in order to reconstruct the volunteers’ biographies.

Why?

For one, because Argentina doesn’t have the kind of archival resources that can be taken for granted in Europe or the United States, whether we’re talking about municipal archives or scholarly bibliographies. This means that, as a historian, you have to go in search of alternative channels of information that demand other kind of methodologies.

What do you hope your book will help accomplish?

As said, one of my goals is to counterbalance a historiography that has been excessively focused on Europe. The war in Spain was fought primarily by the Spanish people, of course, but they were helped by volunteers from around the world. Focusing on Europe elides the extent to which events in Spain were shaped by, and had an impact on, individuals and collectives involved in revolutionary processes elsewhere—including in Tucumán, Río Negro, Córdoba, and Buenos Aires. These were people who left behind their land, job, house, or family to serve the cause of human progress.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College.