What Do We Know About Salaria Kea’s Irish Husband?

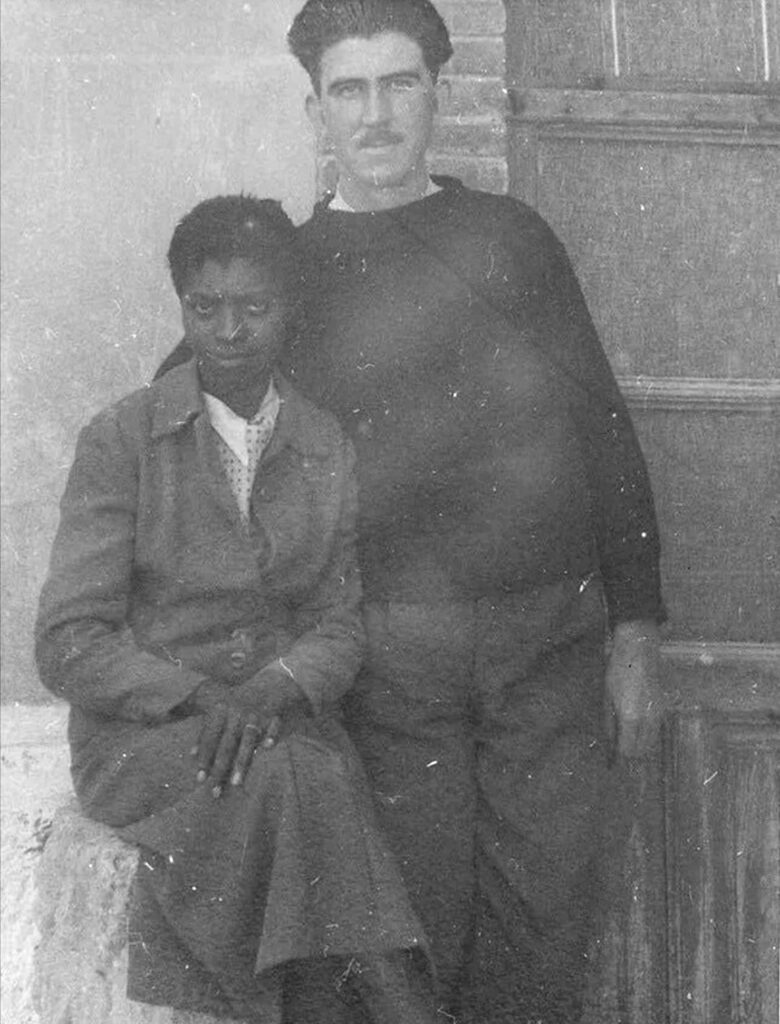

Salaria Kea, the only woman among the close to 100 African American volunteers who left for Spain from the United States, married an Irish ambulance driver. Who was John O’Reilly?

On December 11, 1937, the Baltimore Afro-American published a brief note under the headline “NY Nurse Weds Irish Fighter in Spain’s War,” by Langston Hughes. A leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes had traveled to Spain in 1937 to pen a series of reports on the Black American volunteers fighting in the civil war. He wrote: “Miss Salaria Kee of Harlem, charming nurse at one of the American hospitals in Spain, was married on October 2nd to John Joseph O’Reilly, ambulance driver from Thurles, County Tipperary, Ireland. Her husband was one of the first international volunteers to come to fight on the loyalist side in Spain and was for several months in the trenches. Recently, he was transferred to hospital service.”

A mixed-race marriage among the volunteers provided a perfect example of the progressive racial politics of the anti-fascist Left that Hughes’s dispatches sought to illustrate. Since then, much has been written about Salaria Kea, the only woman among the close to 100 Black volunteers who left for Spain from the United States. Much less is known of the man from Tipperary to whom she’d remain married for almost fifty years.

Among the 35,000 or so International Brigade volunteers approximately 260 were Irish born. Some traveled directly from Ireland while others were economic migrants in Britain. Among these latter was Salaria’s future husband. John Joseph O’Reilly was born in Thurles, County Tipperary on March 29, 1908, the third of four sons. His father was a laborer who fought with the Royal Irish Regiment during World War I. The details of John’s life before Spain are rather sketchy. They rely almost entirely on his own testimony recorded by researcher Fredericka Martin in June 1977 and now deposited in the ALBA Archive, in which he makes no reference to his early childhood. Yet a 1975 interview in the Cleveland Magazine mentioned he “had grown up poor in Ireland. Poverty had been the grinding fact of his existence in a country where jobs were scarce at the best of times.”

By his own account, John left Thurles for the first time at the age of fourteen to live and work on his widowed aunt’s small farm on the Tipperary/Waterford border. The intention was that he inherit the farm, but he found the remote rural life stultifying. Later, he would tell Fredericka Martin: “in the city you had people around you, in the country it was just loneliness.” At the age of twenty, he went to England in search of work. Soon, he would join the Irish Guards regiment of the British Army—“not,” as he recalled, “out of any particular inclination to be a soldier but simply because it was a paying job.” He had signed up for a seven-year period but served three years before deserting. There followed five years of travelling between England and Ireland working as a building laborer and a tannery worker.

Over time, his political allegiances evolved from a narrow nationalism to Republican socialism. There is no evidence that he was ever a member of the IRA, although he was probably a member of the Sinn Fein party. He joined the Irish Transport and General Workers Union in 1934 during a concerted push for unionization in his hometown that was resisted fiercely by local employers. He left Ireland for the last time in mid-1936 never to return.

When recruitment for the International Brigades began in September 1936, O’Reilly was working in a brickyard in Oxford. He regularly attended public meetings in the university common, many of which focused on the situation in Spain, and he came upon a newspaper advertisement seeking volunteers. While there is no precise record on when O’Reilly went to Spain, a December 1937 newspaper interview with Salaria Kea conducted by Nancy Cunard seems to indicate that he travelled in December 1936.

With the influx of British and Irish volunteers, an English-speaking battalion (the Marseillaise) was formed and attached to the XIV (Franco-Belgian) Brigade. Among its No. 1 Company comprising 145 volunteers were 43 Irishmen including O’Reilly. On Christmas Eve 1936 this battalion set out for the Córdoba front. The No.1 Company was led by a controversial though effective officer, George Nathan, who had served with the notorious British Auxiliaries in Ireland. He was assisted by IRA veteran, Kit Conway from the Glen of Aherlow in County Tipperary. The Company’s task was to capture the strategic town of Lopera and ended in failure. Seven Irish volunteers died and many were wounded. In all, 300 members of the battalion died and 600 were wounded.

On January 11, 1937, the much-reduced No.1 Company moved from the centre of Madrid to the outlying village of Las Rozas (now a suburb of the city). The village had been taken by Fascist forces as part of an attempt to encircle the city from the northwest. However, the efforts of the Internationals were stymied by the superior armaments of the rebels and they were forced to retreat, sustaining many more casualties. Of the Company’s original 145 volunteers only 67 returned to the International Brigade base at Albacete. In their absence, a British Battalion had been formed at the training base in Madrigueras from which a group of around 20 Irish volunteers had split and joined the American brigade. O’Reilly decided to stay with the British at Madrigueras. Most of the survivors of those early engagements were then kept in reserve. O’Reilly was appointed as Quartermaster at the British Battalion’s cookhouse with which he soon became disillusioned.

As the Battle of Jarama proceeded, he volunteered for service as an ambulance guard at Morata close to the battlefront. For almost three months he remained in this role, helping to ferry the wounded from the front-line to the reception area in Morata to the hospitals in the vicinity among which was the American No.1 Base Hospital at Villa Paz where Salaria would become head ward nurse. It was here that John and Salaria met in late April 1937. Salaria, newly arrived in Spain, was in the first flush of enthusiasm at this liberating if hazardous experience. Disillusionment on the other hand darkened O’Reilly’s perspective.

O’Reilly describes how he “wasn’t able to take his eyes off her.” Salaria professed to have had no idea of his infatuation. O’Reilly had within two weeks prevailed upon his superiors at the 15th Brigade headquarters to transfer him to Villa Paz. There, he worked as an attendant in the general wards. In an unpublished memoir, Salaria speaks of his quiet, efficient and detached presence. Soon, however, she discovered he was writing poems about her. While none of these poems survive, we do have one poem of his from February 1937. A valedictory poem, it was written during the Battle of Jarama. Titled, “A Dying Comrade’s Farewell to His Sweetheart,” it begins: “You can tell my little sweetheart that I send her all my love. / You can tell her that I love her and in death I love her still. / You can tell her that my body lies where the Jarama river flows, / Where Spanish guns still flash and the Workers’ Army goes…”

Salaria was, at first, reluctant to consider O’Reilly’s advances given the potential long-term difficulties of a mixed-race marriage. She was in the end, however, won over by the sincerity of his pleading. “Would you let the reactionaries take away the only thing a poor man deserved and that thing is his right to marry the one he loved and believed loved him?” They were married on October 2 in the nearby village of Saelices.

Throughout that summer of courtship, the couple were more concerned with duty than with romance. The American Hospital received wounded and convalescent volunteers from battles at Brunete, Belchite and beyond as well as providing much-needed medical services for the local population. In addition, Salaria worked with AMB mobile units closer to the front. After the wedding, she served at the Teruel offensive and the counterthrust by the fascists. She became detached from her unit in the chaos of retreat and was briefly jailed by Republican political police grown paranoid with fears of desertions and fifth-columnists. In March 1938, the hospital at Villa Paz was evacuated and staff transferred to Vic, a large convalescent hospital 45 miles north of Barcelona.

Within weeks, a group of AMB volunteers including Salaria suffering from what would now be termed post-traumatic stress disorder, were sent back to the U.S. Six months were to pass before the couple were able to make contact again and, even then, only by correspondence. During this time, O’Reilly continued to work at the Vic hospital. Conditions there had deteriorated due to overcrowding and an unsafe water supply. In mid-September an outbreak of typhoid devastated the hospital population. In October 1938, he was repatriated to England. Such was his emaciated state on arrival at Victoria Station in London, he was hospitalized by health authorities for three weeks and then spent some time living in a small refugee camp in Surrey.

Soon began the long process of seeking a visa to the U.S. He was initially given little hope of success by the American Embassy in London. However, Salaria had been reinstated at Harlem Hospital which strengthened his case significantly. His visa was granted and he arrived in New York on board the SS Samaria on August 22,1940. His occupation was listed as leather-splitter which related to his tannery work. In New York, he found employment with the IRT subway which hired so many Irish workers, it was commonly referred to as the Irish Republican Transit.

In early 1943, at the age of 35, John O’Reily was drafted and assigned to the 82nd Engineer Combat Regiment. Training took place at Camp Swift, Texas. The regiment sailed for North Africa in November 1943 and on to Frome in Somerset where they were billeted until the D-Day invasion. The 82nd landed at Omaha Beach ten days after D-Day. The bodies of dead GIs still lay on the sands awaiting transport. Over a period of 11 months, the regiment supported the Allied advance southwards to within 12 miles of Paris and then eastwards across northern France, Belgium. At the Battle of the Bulge in mid-December 1944 they operated for a time as frontline infantry. Their ultimate destination in mid-April 1945 was the city of Magdeburg, 95 miles from the German capital. On May 6, 1945, operations ceased and they began the long journey home.

The Second War Powers Act of 1942 had provided for the expedited naturalization of non-citizens serving honorably in the Armed Forces. Applicants were exempted from many of the routine requirements. In all, 13,587 such overseas naturalizations took place among which was that of John O’Reilly. He received his Certificate of Naturalization in Paris on May 28, 1945 almost five years after his original application.

For Salaria and John, the post-war years began with tragedy. Their only child born in 1946, died after three days. Complications during the birth left her unable to conceive again. In addition, the couple experienced, as many International Brigade veterans did in the McCarthy witch-hunt era, harassment from the FBI. Salaria had long since distanced herself from the Communist Party and, over time, became deeply invested in her religious faith. She remained, however, committed to the ideal of racial equality. Having studied for a B.A and M.A in nursing, she worked as a nursing tutor and played an important role in the desegregation of the nursing profession at several New York hospitals. Meanwhile, O’Reilly moved on from his manual work at the IRT to become a Transport Police officer.

The couple’s greatest struggle, however, lay in the stark realities of a mixed-race marriage in America. In 1945, attitudes were such that a Columbia University Professor of Psychiatry, Nathan Ackerman, could write that marrying inter-racially “is very often evidence of a sick revolt against society.” Until the mid-1950s the couple lived in a “neutral,” mainly Jewish area. Later they moved to a house on Grace Avenue, the Bronx, which in time they would be pressured to leave because of racial attacks and intimidation.

In 1973, the couple moved to Akron, Ohio, where Salaria had grown up and where her married brothers and their families lived. Here, they experienced the positive impact of a close and caring family network but also a number of unseemly incidents including receipt of an anonymous threat purportedly from the KKK after having attended Sunday Mass together. During these years, Salaria suffered increasing mental health issues and was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

John O’Reilly took care of his wife through these difficult years for as long as he was able to. When he died on the December 31, 1986, Salaria had already forgotten who he was. She died on the May 18, 1990. They had met at Villa Paz—the House of Peace— and now they lay in peace side by side in Glendale Cemetery, Akron.

George Nathan, cited above, was and remains the prime suspect in the assassination of IRA commander and Limerick Lord Mayor George Clancy in March 1921, during Ireland’s War of Independence. See https://theauxiliaries.com/INCIDENTS/limerick-mayor-shot/limerick-mayor-shot.html

Hi Mark,

thanks for the great article. I am Irish and researching this very topic and would really like to speak with you. Would you care to PM me please? It is in relation to Salaria and her husband.

Kindest regards,

Hi Mark,

I am trying to leave a comment but it keeps “timing out”. I would like to contact you in relation to this subject. Tnx

Mark, I’m curious about your comment about Salaria mistakenly being taken by Republican police. That actually makes a lot of sense, but I was wondering where you got that information because it’s quite a bit different than anything I’ve seen. I would love to know more!

Cathal, I’m doing research as well, perhaps we could share our notes? feel free to email me at cliffnhansen42@gmail.com.