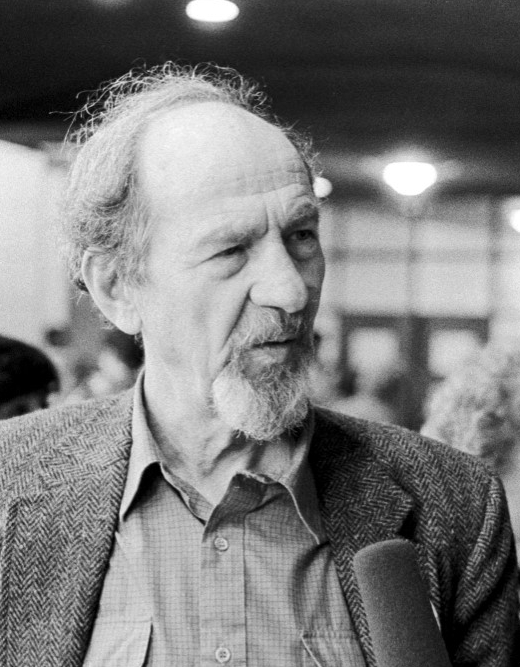

Sydney Harris, UK-born Lincoln Vet

Born in Leeds, England, Syd Harris ended up in a Chicago orphanage when he was five. Fifteen years later, he volunteered for the Lincoln Battalion. After the war, as a well-known labor photographer and journalist, he was targeted by the FBI. A former boxer, he also acted as Paul Robeson’s personal bodyguard when the singer performed in Chicago.

My father, Sydney Harris, was born in Leeds in 1916 to working-class Jewish parents. His father had been a medic with the British army in World War I and suffered lung damage from mustard gas, and his mother died in the influenza plague in 1919. Traveling to America, his father put Syd in a Jewish orphanage in Chicago at the age of five, where he stayed until he graduated high school.

Leaving the orphanage in the middle of the Great Depression wasn’t easy. Syd began to box at the Golden Glove level, and when his stockyard foreman called him a “kike” Syd knocked him to the floor and got fired. Syd had begun to hear about fascism, its anti-Semitism and its threat to democracy. So, in 1937 he joined the Young Communist League and decided to volunteer for the Lincoln Battalion.

When Syd got on the bus for the trip to New York, Eddie Balchowsky came walking up, his arms around two girls and a bottle of Champagne in hand. Eddie was from a well-off Jewish family and had been studying to be a concert pianist at the University of Illinois. But Eddie was on his way to Spain too, and so the working-class, orphan kid and the radical, privileged student were to become life-long friends. On their way to Communist Party headquarters in New York, Eddie heard someone playing Mozart from a second story window. Eyes bright with passion he turned to Syd, pointed to the window and said, “That’s why I’m going to Spain!”

Syd and Eddie got to Spain in late November 1937. Eddie was assigned to scout for the Canadian Internationals and Syd stayed with the Lincolns. Syd grew up reading Rudyard Kipling and said at the training camp in Figueras it broke his heart to learn that Kipling was a big imperialist. But years later he still liked to quote the ending of Gunga Din. “You’re a better man than I,” said the British officer to the water boy Gunga Din. That’s the lesson he took from the book.

Syd became a sergeant and fought at Teruel in the winter of 1937-38. But in the spring during The Retreats he was shot and captured in April, 1938. For a month the Lincolns had battled and retreated, first from Belchite, to Albalate, Caspe, and Maella. Finally, they tried to break through the fascist lines to reach the Republican held city of Gandesa. Failing to win, the Lincolns retreated to a hill overlooking a small valley.

Syd was ordered to take three men across the central valley road, up the facing hill to look over the heights and report back on enemy activity. But while separate from the battalion a company of fascist cavalry came riding through the valley. The Lincolns opened fire forcing the fascists up the opposite hill riding straight towards Syd and his comrades. Firing from behind a tree he heard a rustling from behind. Quickly turning he saw a soldier on horseback aiming his rifle straight at his head. But Syd’s quick movement spooked the horse into rearing, and when the shot went off it hit his ankle. Knocked off his feet he went tumbling down the hill smashing into a boulder with the cavalryman in quick pursuit. But to get a shot the fascist would have to expose himself to fire from the Lincolns and instead retreated up the hill. The battle was soon over and both fascists and Lincolns abandoned the area.

Syd found himself alone, with two grenades, a gaping wound and unable to move. As the sun was going down, he spied two women clothed in Spanish black walking down the road. One was an older woman and the other, Suzanne, just 17 years old. They were Republican supporters.

They promised to come back and as night set Suzanne reappeared with an orange and egg. By this time Syd was going into shock and shaking from the cold. Suzanne held him throughout the night, keeping him warm in her comforting arms. It was the first time Syd had spent the night in the arms of a women. In the morning she went to seek help, but before she returned, Italian fascists appeared picking up the dead.

Spying Syd, they rushed up shouting, “You red bastard we’ll kill you right here, you fucking Russian Bolshevik!” Syd cried out, “No, no I’m American from Chicago, Chicago!” Suddenly the shouting stopped. The Italian lieutenant cocked his head, “Chicago?” Syd replied, “Yes, for Christ’s sake Chicago!” Suddenly a broad smile broke out on the lieutenant’s face. He fired off his machine gun into the air, looked at Syd, and said, “Chicago, home of Al Caponé! Take him alive!”

Dragged into town Syd was thrown into a barn and fell into an exhausted sleep. A little while later he woke to shouts and kicks with German soldiers standing over him yelling, “You red bastard we’re going to kill you right here, fucking Russian Bolshevik!” The Italians rushed in and an argument raged over who owned the prisoner. Lucky for Syd, in Italy’s first victory over Germany since the Roman Empire they managed to expel the German troops.

Syd was sent to a prison hospital in Bilbao where he spent four months. While there the Spanish authorities were letting a German doctor experiment on the patients. In a letter Syd wrote, the “fascist hospital reminded me of the slaughter and butcher houses back home…Injections were given only to the Internationals to ‘make your blood better’.” After two died and a third went out of his mind the prisoners rioted and tore up the ward, and the hospital administration finally removed the German doctor.

Syd was sent to the prisoner camp for Internationals at San Pedro de Cardeña. As the 700 prisoners lined-up for review a colonel led them through salutes to fascist Spain. The last was a straight-arm salute to Franco. But instead of shouting Franco the men let out the cry, “Fuck You!” The colonel looked sternly at the men, and then smiled. “Otra vez!” “Fuck You!” “Uno más!” “Fuck You!”

Syd turned to the guy next to him, “What the hell is going on?”

“The colonel doesn’t speak English, and to him fuck you sounds like Franco with an English accent.”

But life at the prisoner of war camp was anything but easy. Syd recounted his experience writing:

“Cold cement floor full of holes, broken stairs, thousands of mice, rats and vermin of all kinds… As we drove in we received our first view of what was later was to be a daily occurrence: a sergeant with a long leather reinforced twisted cane-whip, lashing out among a group of men. We all had our share of beatings from shell shocked sergeants who didn’t even try to give any reasons in explanation of their actions. Too many of us bear scars from sticks, rifle butts, fists or boots, they used them all. They got a genuine pleasure and joy in making and seeing us as miserable as possible.

“Always hungry, unable to concentrate, to exercise, lying on louse- and flea-ridden mattresses all day waiting for a ladle full of beans and two rotten sardines. Clothed only in pants, shirts, and slippers in a cell with damp and windy climate; no wonder ten of our comrades died and most of the others were sick all the time. Three water taps for seven hundred men to wash themselves, their clothes, and plate in…planning for the day when once again we could be MEN. Freedom. Liberty, how we appreciate those words now.

“But in the midst of that feeling comes the thought of our comrades, especially those from the countries dominated by fascist, who are still in national Spain. Always picked upon to receive the worst treatment by the guards they have the courage, self discipline, and intestinal fortitude that belongs to men convinced of the righteousness of their actions and a deep and everlasting love of liberty and democracy. May the day be soon that they also can once again breath the fresh air of liberty and freedom for which they sacrificed so much to defend, until then Salud comrades.”

When he went to Spain Syd was still not an American citizen, and so was released with the Canadian Internationals. He returned to the US by way of Toronto, married Rose Fine, and became a well-known labor photographer and journalist. He served as head of the Lincoln’s Veteran’s Lodge and often organized security for Paul Robeson when he sang in Chicago, acting as his personal bodyguard. During the McCarthy period the FBI threatened to deport him back to the UK, but Syd held strong, remained politically committed and active, and became a US citizen in 1957. He named his first son Paul after Robeson, his middle name Aaron, after Aaron Lopoff. Lopoff was Syd’s commander in Spain who he described as the “bravest man he ever knew.” After five sons, his last child was a girl. He named her Suzanne.

Historian Jerry Harris has co-edited Chronicles of Humanity: The Photography of Sydney Harris. His latest book is Global Capitalism and The Crisis of Democracy. This story was first published in No Pasarán (2-2021, Issue 57) the magazine published by the International Brigade Memorial Trust (United Kingdom).

Jerry!!! What an amazing journey of courage your father was on since the age of five! The details of your article fill out the vague memories I had of your dad’s life! I was so incredibly blessed to have met him…in Chicago…and for him to have taken photos of me at 16, visiting my brother Jeffry …who was staying with Syd. Damn!! I had several friends whose parents were in the Lincoln Brigade. Jack and Janet Shapiro’s father died in Spain.

Thank you so much for this tribute to your father! Much love…Jo

Thanks for writing this account of your Dad’s life, Jerry. I met Syd as a labor photographer while I was an editor of two union publications for the AFT and the UAW. He was a talented and sensitive photographer, and we used his photos to help tell some of the stories we published. I had no knowledge of his courageous service as a volunteer in Spain, but I certainly knew of his work with Paul Robeson, as he gave me a large print of a photo of Paul.

I’m so happy that I ran across you story in The Volunteer.