Voices from the Spanish Earth

The Volunteer is proud to present these translated excerpts and images from Las voces de la tierra, a new book in which thirty-three writers pen brief texts about everyday objects recovered during the exhumations of the mass graves of Franco’s victims. The photographs are by the renowned photographer José Antonio Robés, who also curated the project. The book commemorates the twentieth anniversary of the birth of the Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, co-founded by Emilio Silva, the 2015 Recipient of the ALBA/Puffin Prize for Human Rights Activism.

The Volunteer is proud to present these translated excerpts and images from Las voces de la tierra, a new book in which thirty-three writers pen brief texts about everyday objects recovered during the exhumations of the mass graves of Franco’s victims. The photographs are by the renowned photographer José Antonio Robés, who also curated the project. The book commemorates the twentieth anniversary of the birth of the Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, co-founded by Emilio Silva, the 2015 Recipient of the ALBA/Puffin Prize for Human Rights Activism.

From the Prologue

By Emilio Silva

These objects are motionless stars of the anti-heavens, little suns that remain dead while they remain hidden […]

This book is an astronomical guide to those constellations buried in dirt, a collective reflection on the disappeared who now appear because what conceals them is also what preserves them, like islands united by what separates them, the sea.

The objects that have been photographed by José Antonio Robés were uncovered in exhumations of mass graves, in places pointed out by witnesses, in out-of-the-way ditches, by the side of little frequented roads, in unconsecrated corners of cemeteries where the nameless bodies of those who, before being murdered, had rejected the sacrament of confession. […]

Robés has decided to photograph the objects in black and white, as if they would appear more naked when stripped of color. The idea was to speak of the disappeared and exhumed people from a shard of their lives, from something that they carried, which they kept until the last moment.

The photographs were taken in archives and in family homes… Later, a selection of the images was sent to those who have written the texts, and the authors were offered the possibility of receiving information regarding where, when, and next to whom the objects had appeared.

An earring, a pair of boots, a die, a lighter, a piece of paper, several shoe soles, a scrap of paper, a box, a knot of wood, a bowl, a ring, a pair of cufflinks, a lead pencil, a comb, a rope lighter, unfired bullets, a pencil, a spent bullet, a razor, a belt, a medal, a watch, teddy bears, a pencil sharpener, a domino, a buckle, a coin, teeth, hairpins, glasses, a key, a toothbrush, buttons, a baby’s rattle, a badge, a pipe, a crucifix, and Maria’s glasses.

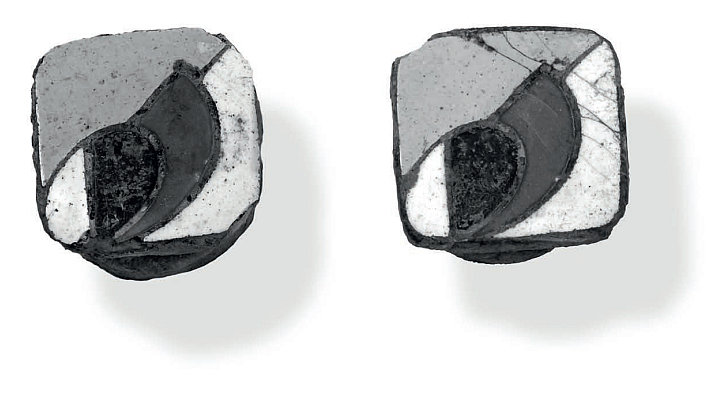

Two Cufflinks

By Olga Rodríguez

The two cufflinks are two eyes that stare at us, demanding that we look back at them. Demanding that we look back at all those things that this country has been unable to face for decades: our memory, our past, which will be our present until we spread the knowledge of who we once were, so that we can finally understand who we are. When we look at the cufflinks how can we not think about the eyes of the person who was wearing them when he was shot? Designed long before the crime, they have come to represent, in a sad metaphor, the sleeplessness of the forgotten, in this country which will never enjoy full and robust democracy until it abandons its collective amnesia.

For decades, these two cufflinks or eyes have remained open, never even blinking, waiting for someone to find them, waiting for a burial, for a farewell, for some words of kindness, truth, justice, reparation. There are silences that scream out, and the gaze of this inert object is one of them. It asks us: until when will we ignore the 114,266 people disappeared by Francoism? It reminds us that Spain continues covering up the crimes of the dictatorship, invisibilizing the disappeared, denying recognition and aid to the families of the victims, giving the assassins the benefit of the doubt, silencing the victims. It tells us in whispers that the democratic health of this country is at stake; because only with justice and the defense of human rights can we arrive at a necessary consensus: that committing crimes against humanity must have a price, so that they are not committed again.

The owner of these eyes was a tailor. His name was José Rodríguez Silvosa. He was shot and disappeared on August 10, 1938. His two jewels, used to button up shirt sleeves, found beside his remains, still look us square in the eyes. Until when?

A Comb

By Sukina Aali-Taleb

A ringing in the ears and with a gunshot his life slipped away. He thought this wasn’t about him. Death is never about you. Only others ever die. Nor did he think that being dragged out of his house was about him. He thought it had nothing to do with him because a good man cannot pose a danger to anybody. That night he dreamt again that he was descending the steps carved into the rock down to the river. Before waking up, he came to a green meadow where women were spreading white sheets in the sun. That morning he was awakened by the barking of dogs. And just before hearing the ruckus being made by the girls, he thought about how that night would be for dancing. They called out his name, but he did not hear from his far-off bedroom. He dressed quickly and hurried down the stairs. They took him out of his house at gunpoint.

He often dreamt of studying, of going to the capital. And of returning to the village knowing all about agriculture. He discussed plans with friends at the Casa del Pueblo one Friday. Between the house and the stables, where they would hit him on the back. From the makeshift prison to the back of a truck with other boys. Lying down on the grass, while the four cows grazed, he thought that if he studied, he could travel, see America. He could help change things. He could pay a doctor to give his grandfather new teeth. He could one day buy land in the high part of town where potato crops did best. He could have two jackets and some shoes that he would joyfully polish at dawn. Inside the truck, the young men kept quiet. They crossed the bridge over the river. The music did not sound far away. They got out of the truck. The women were laughing as they walked down to the verbena.

Shots rang out, the music in the town stopped. A gunshot to the chest. He thought of the fluttering of a white sheet that covered his eyes. He fell to a green meadow dimmed by the night, and the comb he kept in the inside pocket of his best jacket slipped out.

Colonel Benito

By Isabel Cadenas Cañón

Sometimes I play a game in class with my students. I show them Spanish Civil War posters, and they have to determine which side produced each poster. They have doubts about some, others they tend to get right, but there is one in particular that almost always trips them up: Against a red background, a soldier holds a basin of water while he washes his head with a sponge. The text: “Soldier! Be clean! Hygiene is the key to health.”

The poster was created by Bardasano in 1937. But neither the red background nor the red star that appears below the caption –not even the artist’s signature– lead my students to guess that this might be an image of Republican propaganda. Automatically, they associate hygiene and cleanliness with right-wing values. That is another battle that we have lost.

Then I think about a man who loses a war and goes into exile in the Soviet Union, where he fights against Nazis in another war that is really a continuation of the first one. I think of how he returns to Galicia to help organize the Communist Party’s guerrilla operations. Of how the operation falls apart, and how our man takes on the task of reorganizing it. Then the rumors start: he is too military; he is distancing the guerrilla movement from the people; he is a leader; he is an infiltrator. I imagine him hiding out in the mountains, with two compañeros, and then the ambush by Civil Guards.

I think about the day they killed him. How the man who wanted to militarize the guerrilleros was carrying a toothbrush in his pocket.

A toothbrush with which to rewrite history.

Las voces de la tierra. Madrid: Asociación para la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica/ Editorial Alikbla, 2020. To order the book, click here.

Curation of this selection: James D. Fernández; translations: Alejandro J. Fernández.