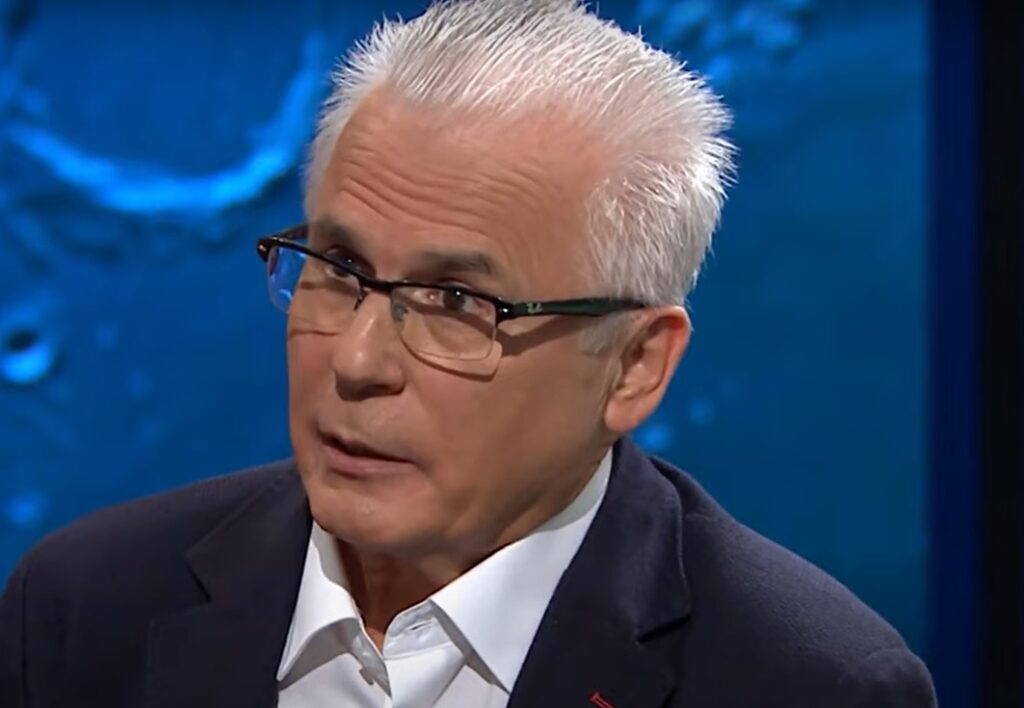

Baltasar Garzón: “There’s Nothing More Dangerous Than Friendly Fire.”

Judge Garzón, the crusading Spanish magistrate and first recipient of the ALBA/Puffin Award, looks back on his turbulent career. “The truth is that my ideas have not changed much.”

No Spanish judge has had as many admirers around the world as Baltasar Garzón—the Spanish judge who helped bring about a world in which political leaders are held accountable for human-rights abuses committed under their rule—and none has had as many detractors, including in his own country. (See below for a brief biography.) I spoke with Garzón in December and January 2021. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Over the past 40 years, you have been a judge, a politician and a public intellectual. How have those different experiences in Spanish public life shaped your ideas about the problems facing your country?

Although both my role and the context have changed a lot, the truth is that my ideas have not changed much. I began working as a magistrate in the late 1980s, when the judiciary was still weighed down by the legacies of Francoism. I remember the impatience I felt at the Audiencia Nacional with the magistrates’ lack of empathy with the real world. The judicial investigators would take police reports at face value without bothering to look at the facts on the ground. I have never operated that way. Rather, I have always insisted on doing my own investigations and showing up at the crime scene. That is how I earned my first antipathies, I think.

Your colleagues didn’t appreciate your way of working?

I now understand that I was probably embarrassing them. I had a hard time understanding why issues of such importance as drugs and organized crime were not addressed comprehensively or why there was a fear of the drug lords. I can understand that in areas such as Galicia or Andalusia it was more difficult to deal with them—but that is why we were the judges of the Audiencia Nacional: to attend to the victims when they reported crimes and asked for help. We organized operations like “Nécora” or “Pitón” to deal a blow to organized crime in Galicia and Andalusia, respectively, and to contribute, above all, to the fight against youth drug addiction. During my stint as junior minister in charge of the National Plan on Drugs, I had the opportunity to contribute in a more direct way to public health focusing on prevention, suppression, and recovery programs for addicts.

In addition to your fight against drug trafficking, you first became known for your fearless prosecution of both ETA and the State’s dirty war against it.

One of my life-long principles has been the defense of victims. I strongly believe a judge should be independent, prosecute crime, and apply justice based on law. But, above all, he or she should attend to the victims by penalizing the victimizers. That has always been my guide, whether I worked to dismantle the terrorist organization ETA, which has brought so much suffering to our country, or the GAL, which committed execrable crimes and were a form of State terrorism. I have worked in the same way as a magistrate in each and every one of the cases I have had to deal with, without paying heed to pressure or tolerating any attack on my professional integrity. This is what a judge must do—and this is how I have always worked.

As a politician, I applied the same criteria, making decisions based on equity, justice, and protection of the vulnerable. My short time in politics allowed me to understand the country’s problems from another perspective—that of those who are obliged to govern and compromise in order to move forward with budgets or laws. But I also learned how much theater there is in politics, and how little citizens get to find out about what goes on behind the scenes. My experience in politics, I think, accentuated a certain skeptical vein that I continue to use as a shield to defend myself from politicians.

Scroll down or click here to continue reading the interview.

Garzón: A Life in the Spotlight

Born in 1955 in a small peasant town in the southern province of Jaén, where his parents and grandparents were farmers, Garzón spent his teen years at a seminary preparing for priesthood but then chose to pursue a legal career instead. After earning a law degree from the University of Sevilla, he briefly held positions in the Basque Country and his native Andalusia until in 1988, at age 32, he was appointed as investigative magistrate to the prestigious Audiencia Nacional in Madrid.

An unusual court, the Audiencia Nacional has jurisdiction over the entire national territory and specializes in “major crimes,” including terrorism, financial crimes, drug trafficking, and international crimes. In the years following Spain’s transition to democracy, it was the Audiencia Nacional that took on the prosecution of ETA, the armed wing of the Basque independence movement, in part because the courts in Basque country itself were thought to be subject to undue pressure.

At the Audiencia, the young and photogenic magistrate assumed a central role in the prosecution of ETA and the illegal drug trade. In 1993, Garzón’s quickly rising fame as a judge earned him a brief stint as a junior minister in the cabinet of the Socialist prime minister Felipe González. Soon after, back at his judicial post, he indicted officials in the González administration who were involved in an illegal paramilitary operation, known as GAL, that targeted presumed members of the Basque organization. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the judge helped revolutionize international law when he invoked universal jurisdiction to prosecute former heads of state in Latin America and elsewhere—including, famously, former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet in 1998—for human rights violations committed under their rule, helping accelerate what Kathryn Sikkink has called the “justice cascade.” After 9/11, he indicted Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden. In 2008, he responded to requests from victims of the Franco dictatorship by initiating Spain’s first-ever judicial investigation into crimes against humanity committed during Franco’s almost four-decade rule. The next year, he investigated a major corruption ring that centrally involved Spain’s conservative Partido Popular (PP) and became known as the Gürtel case.

In all these high-profile cases, Garzón made powerful friends and enemies. While he is admired by many for his judicial doggedness, tireless drive (he reportedly gets by on three hours’ sleep), and political courage, others look askance at what they see as his inappropriate taste for notoriety. (Garzón, whose 2016 memoir is titled “In the Spotlight,” says he’s never sought out publicity for its own sake.) Some critics also maintain that his prosecution of ETA and the pro-independence Basque Left glossed over systemic acts of police brutality and infringed on civil liberties, including freedom of speech and association—accusations that Garzón has always denied. The Basque politician Arnaldo Otegi, who was sentenced to prison after an investigation initiated by Garzón, recently suggested that Garzón adopted a hard line on his case in an effort to placate the right-wing powers that, by then, had set their sights on the judge himself as well.

Indeed, as time went on, Garzón faced increasing pressure from the Spanish Right, including his conservative colleagues in the judiciary, until in 2009 and 2010 he found himself as a defendant before Spain’s Supreme Court. He was charged in three separate cases, one of which was related to the PP corruption ring and one to his attempt to investigate Francoist crimes. Although he was absolved in the latter case, in 2012 he was found guilty of illegal wiretapping in the corruption investigation and disbarred for eleven years. The sentence, widely seen as a settling of political accounts, set off an international firestorm. So did the Court’s opinion in the case of the Francoist crimes, which in effect closed off any possibilities for the victims to pursue their quest for truth and reparation through Spain’s criminal justice system.

Since then, Garzón, who turned 65 last year, has not moved far from the spotlight. He has taught at the Center for Human Rights of the University of Washington, Seattle; consulted on the peace process in Colombia; and worked as a lawyer in private practice. Together with the late Michael Ratner, he served on the legal team of Julian Assange as the creator of WikiLeaks fought extradition. In 2017 Garzón helped found, with limited success, the progressive political party Actúa. Recently, Garzón’s name has popped up in the wide-ranging judicial investigation of José Manuel Villarejo, a powerful former police chief and all-round sleuth used by several governments to target political enemies with defamation campaigns. (Although Garzón was one of Villarejo’s victims in the early 1990s, the two later became friendly.) Garzón has three adult children. For the past several years, he’s been in a relationship with Dolores Delgado, a former prosecutor and minister of Justice who currently serves as Spain’s attorney general.

In the course of his career, Garzón has published half a dozen books, including, most recently, La encrucijada: Ideas y valores frente a la indiferencia (The Crossroads: Ideas and Values in the Face of Indifference). In 2011, Garzón was the first recipient of the ALBA/Puffin Award for Human Rights Activism. Today he combines his job as a lawyer with the presidency of the International Baltasar Garzón Foundation, which works to strengthen democracy and human rights worldwide through education, research, and consulting.

You left politics quickly and, if I remember correctly, quite disenchanted.

My disappointment with politics had to do with the impossibility of the task to which I had committed myself and the President of the Government had committed himself, which included the fight against corruption and the coordination of police operations in the fight against organized crime. When I saw that there was no political will to resolve those urgent tasks, I resigned. I have never been interested in public office, no matter how much I have been called a star judge with ambitions. Whoever claims such a thing does not know me or seeks to discredit me. I have always followed my conscience as a public servant.

Or, more recently, as a public intellectual.

I prefer to see myself as a human rights activist, albeit one who works from a privileged position because of my relationship with historic figures such as Pepe Mujica, Lula da Silva, Rigoberta Menchú, José Saramago, the Grandmothers and Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, Ernesto Sábato, and so many other great politicians, thinkers and dedicated men and women whom I am honored to call good friends.

To get back to my initial question, do you see the problems of Spanish society differently now than when you started out?

My views have evolved with the times. In the 1980s, Francoism was still in force in different social strata as the country began its sudden and difficult path towards democracy. Today, we find ourselves in a more modern society, for which democracy is by now a given, but in which, once again, neoliberalism and fascism rear their ugly heads and give us reason to fear a regressive return to the past.

The problems of unemployment, social inequality, gender violence, and threats to rights such as freedom of expression are a consequence of the fact Spain has had too many years of right-wing rule. They are also the result of a weakness of the Left, which has been fragmented, as it has been so often, and not very determined to work together. This has given wings to the most conservative fringe of the Popular Party and has provoked a rise of the far Right that would have been unthinkable only a few years ago. Of course, Spain is no exception in this regard. Just consider the situation in Hungary, Poland, or Brazil—not to mention Donald Trump who, through acolytes like Steve Bannon has inspired minority parties in Europe that have achieved unsuspected electoral victories.

Yet in your most recent book, En la encrucijada, you are hopeful about the future. You point to the mobilization of citizens around the world that we saw before the pandemic.

That’s right. I am thinking, for example, of the mass mobilizations of women or other social movements in Latin America. I sincerely hope that, after the pandemic, we’ll see a return of those healthy civic exercises in which citizens remind the politicians that the politicians are at their service and not the other way around.

What lessons do you draw from the public health crisis of the past year?

If the pandemic has shown us anything, it’s that those countries least affected by neoliberalism have been able to respond better to protect their citizenry. I think that this experience should generate a new commitment that goes beyond the concepts of Right and Left, which I think have been superseded. The task today is to join progressive forces with the moderate center against the rise of the far Right. In the coming years, coalition governments will be key in this effort. In Spain, many still balk at that idea or think it will never work. But that view is rooted in ignorance. Remember that, of the 28 countries in the European Union, 20 are governed by coalitions, some of which join parties with very divergent views. And yet they make it work. In many countries, this has long been the norm. In Spain, we have a lot to learn—and I am including politicians in that statement.

Your relationship with the State, including the courts, has been rather mixed. You have been an agent or representative of the State—for example, as a member of the judiciary—but also the object of its persecution, from the smear campaigns in the 1990s to your trials in the Supreme Court in 2009-12. Have those experiences changed your view, in hindsight, of your own work as a judge?

The persecution you mention is part of a fundamental aspect of the role of the judge: independence. I have seen myself attacked, as you say, by a leftist government when I investigated the dirty war against ETA, and by a right-wing government when I investigated the Gürtel case—the most important case of political corruption in the history of Spanish democracy—or when I initiated the investigation of the crimes of Francoism. All these attacks, in the end, only served to reaffirm the integrity with which I have always approached my work, whomever it may please or displease. I have been the target of dirty campaigns since my first years at the Audiencia Nacional. The reason is simple: discrediting or questioning the judge is common tactic for those who seek to annul a procedure or sow doubt. In the Gürtel case—affecting the Popular Party, which by then was in government—the attempts to discredit me were constant from the very beginning. And once I was off the case, they targeted the other judges who continued the investigation or were in charge of the sentencing.

Look, you must understand that we are talking about people who have no scruples about committing crimes, who fear a conviction and seek to slander the judge in an attempt to save their own skins. I continue to believe that my role as examining magistrate is correct as I have exercised it. What has changed, however, is my view of some colleagues who, for reasons that only they can know, have not conformed to the law when resolving cases like mine. Beyond my own conviction or acquittal, what still baffles me is the trial I was subjected to for declaring myself competent to investigate Franco’s crimes. While the sentence of the judges of the Supreme Court’s Criminal Chamber acquitted me—the international outcry, after all, was strong—in effect it condemned the victims, because the judges decided that these crimes could never be investigated through the criminal justice system.

Their verdict amounted to a full-stop law.

Exactly. But a full stop is impossible when it comes to crimes against humanity—which is what the crimes of the Franco dictatorship were—because those are cases in which statutes of limitations don’t apply. That Supreme Court decision definitely changed the way I saw my colleagues on the bench.

These days you frequently write for the media and you have a regular column in the online daily InfoLibre. How do you assess the evolution of the Spanish media over the last ten years, when we’ve seen the long-dominant conglomerates and their printed newspapers lose much of their influence?

The media have certainly become more fragmented as Spain has changed. And of course, there’s been the emergence of social media, through which true or false information travels at lightning speed. Financially, the print media have seen a drop in advertising revenue as advertisers have discovered that social media or phenomena like online gaming are a cheaper and more effective ways of reaching the consumer. On the other hand, newspaper companies are no longer, as they were in the past, the sole property of a family or a veteran businessman in the sector. Now, the shareholders include other companies and investment funds that are less committed to the truthfulness of the information than to supporting specific policies or entities.

I remember that a journalist friend of mine told me that, in the past, when newspapers reported on traffic accidents, they would never mention the speed of the vehicles as a cause of the crash. The reason was simple: The automobile industry was one of the main sources of media publicity and was interested in maintaining the idea the cars they sold were both very fast and very safe. In that instance, the media clearly bowed down to financial pressure. Today, similar things occur. We see vulture funds or real estate moguls serving on the board of directors of media outlets that demand that the government apply a hard hand to squatters. Or we see businessmen with major shares in media companies that support a certain political candidate from another country—for example, Venezuela. That explains why in Spain we so often read more about what is happening in that country than about the problems we are experiencing here. On the other hand, there are honest and progressive online media that try to survive against the odds, such as InfoLibre, ElDiario.es, CTXT, Público, or Nueva Tribuna.

The large media outlets, in other words, still wield significant power, in part through their shareholders. And that power is not limited to print media. It also extends to television, where politics often becomes a show, or the radio networks whose bias depends on the company that owns them or the political orientation of the national or regional government that supports them. In the end, journalistic independence is increasingly curtailed by economic and political powers.

How do you see the balance between the constitutional right to freedom of speech and a democracy’s need to protect itself? As a magistrate at the Audiencia Nacional in 1998, you took the controversial decision to close a Basque newspaper and radio station associated with ETA. The newly proposed Law of Democratic Memory would make an organization like the Francisco Franco Foundation illegal. On the other hand, Spain has seen recent cases where rap artists and Twitter users found themselves indicted for making jokes or singing about the King.

Spain’s courts and the Constitution guarantee freedom of speech. But this does not include hate speech motivated by xenophobia, racism, and the like, especially when it incites acts of violence. We see this happening today in social media, for example in reaction to the pandemic. The new forms of communication pose a challenge for the State, to which in Spain has responded, for example, by creating a commission to detect the spread of this kind of speech through social media and bots. My own decisions in 1998 were based on clear indications of criminal activity, later ratified by the Supreme Court and the European Court for Human Rights.

The State has the right and the obligation to intervene when there is a crime or the appearance of a crime. That said, any official body charged with regulating speech should be fully transparent and fully independent of the other powers. With regard to the rap artists and other cases you mentioned, perhaps the courts have been overzealous in their interpretation of the penal code. In the same way that, in the case against the Catalan independence movement, I believe its leaders should never have been charged with rebellion. But then again, if these decisions were erroneous, they have been —or will be— corrected by Spain’s Constitutional Court or, if need be, the European Court for Human Rights.

Freedom of speech and of the press has also been at the heart of the case against Julian Assange, in whose defense you have joined.

The United States government considered that Assange, who is both an activist and a journalist, posed a threat because he exposed illegal actions of that government that threatened the security and rights of other countries. The persecution that Assange is being submitted to has become unbearable. It has nothing to do with justice. Yet it’s done with the acquiescence of other governments, including the United Kingdom. Attacks on freedom of expression like these are, unfortunately, another sign of the times.

What’s the best way to counter them?

International consortiums of investigative journalists, and actions such as those of the US media, which did not hesitate to call out Donald Trump for his lies. In Spain, too, there are still worthy and truthful media outlets, and I know plenty of journalists who refuse to compromise on their professional ethics. But they always have the threat of losing their jobs dangling over their heads like the sword of Damocles. The job insecurity and precarity in the news media today directly undermines the citizens’ right to information.

A final question. Spanish political culture, perhaps more than some other European countries, is weighed down by clientelism and nepotism. There tends to be very little distance between the world of politics, the State (whether national, regional, or local), the business world, and the media. Your own investigations of political corruption in the PP and other parties make this very clear. So does the collusion among these powers in defamation campaigns of the kind we’ve seen revealed in the Villarejo case. This is a world in which you’ve been operating for close to 40 years. How hard has it been to keep your ethical mettle? Or, to put it differently, is it possible for anyone to be effective in such a system without compromising their moral standards?

Of course, it is possible—and it is paramount. But you do so in the knowledge that, in the process, you are risking your own and your family’s emotional and personal tranquility and stability, and that you will be subject to defamation and insult or even physical harm. Working like this is not easy, especially when it affects the people you love, who suffer because you refuse to compromise your moral standards. And yes, one can be effective despite all that.

That said, sometimes the forces that seek to stop you from doing your work are quite powerful and spare no time or money in their efforts to neutralize you. Now, when those forces are joined by those who should be supporting you—and who, instead of doing that, turn against you and ignore their sacred obligation—then they may succeed in their goal. There’s nothing more dangerous than friendly fire. But look, I am still here, and I haven’t changed my convictions.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College.

[…] Full text at The Volunteer. […]

[…] Baltasar Garzón: “There’s Nothing More Dangerous Than Friendly Fire.” […]

No doubt, Mr Garzón has an unbeatable opinion about himself. And a high reputation in certain international stages. But he has been responsible of questionable resolutions, specially those concerning torture or the closure of the Basque newspaper “Egin”(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egin_(newspaper)

There is no better alibi for human rights abuses than receiving an award for one’s services to human rights from a prestigious international body. When is Anglo-American Hispanism going to address Garzón record on torture (in Cataluña and the Basque Country), his corrupt relations with Villarejo and Florentino Pérez, his failings as a judge? It certainly can’t claim ignorance of the litancy of crimes that Garzón committed as an agent of the very State he claims to be fighting against.