Martha Graham’s Dances for Spain

In June, the Martha Graham Dance Company performed Immediate Tragedy, a long-lost solo piece that Graham performed in 1937 in support of the Spanish Republic. Its reconstruction was only possible thanks to a cache of recently recovered photographs of Graham’s original show. Together with Deep Song, inspired by Lorca, the piece marks a crucial phase in Graham’s development of a new language of dance.

“The battle of Spain is the immediate tragedy of our lives, far more so than the Great War.” This statement from 1937 by Lincoln Kirstein, co-founder of the New York City Ballet, reflects the overwhelming support among the US dance world for the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War. In fact, in 1937 and 1938 the American Dance Association (ADA)—founded in 1937 to secure dancer’s rights, promote world peace, and fight fascism—sponsored two fundraising events called “Dances for Spain.”

Kirstein’s words return in the title of one of the two solos that Martha Graham (1894-1991), one of the most influential choreographers in the United States, devoted to the conflict. Immediate Tragedy: A Dance of Dedication, premiered on July 30, 1937, in Bennington, Vermont. The second solo, Deep Song, inspired by García Lorca’s Poemas del Cante Jondo, was performed at the ADA’s second “Dances for Spain” event, held in January 1938 at the Hippodrome Theatre.

Sadly, there are no filmed records of either of those dances. Worse, both were initially left out of the Martha Graham repertory. Seemingly forgotten, they lay dormant for many years while their musical scores, by Henry Cowell, were thought lost. And yet both dances are crucial for understanding Graham’s trajectory—specifically, her development of a new language of dance with a deep awareness of historical necessity.

In 1988, Terese Capucilli, a principal dancer with the Martha Graham company who’d become its artistic director from 2002 to 2005, worked with Graham to reproduce Deep Song, relying, among other materials, on a series of about 100 photographs from the Barbara Morgan archives. Because the original music had not been found yet (it was later discovered behind a desk on the floor at the Graham Center and placed in the proper archive), they decided to use another piece by Cowell, “Sinister Resonance,” as a score. This is the music used to this day when the piece is performed.

It’s hard to exaggerate the significance of Deep Song. In Terese Capucilli’s words, it “was Martha doing in dance what Picasso did in art.” It had always been Martha Graham’s intent to produce a narrative that could approach the tragedy of the Spanish Civil War while depicting a universal condition—showing, in the words of Robert Burns, how “Man’s inhumanity to man makes countless thousands mourn.” In Deep Song, the dancer’s movement initiates the plucking of piano strings and the music ends while the dancer continues her plaintive movement in silence beyond the blackout. The bench where the soloist moves into the first contraction—and to which she returns time and again after swirling, crawling, reaching, taking in, contracting and falling—becomes the catalyst for the entire piece. The bench is a center of energy that, beginning as a home, or a womb, transforms itself into the trenches where men are fighting, the weight that the woman must carry, the grave that she inhabits for a moment, and the final resting place against which she mourns. In Capucilli’s words, the bench is both a source and a confining element that drives the dancer back.

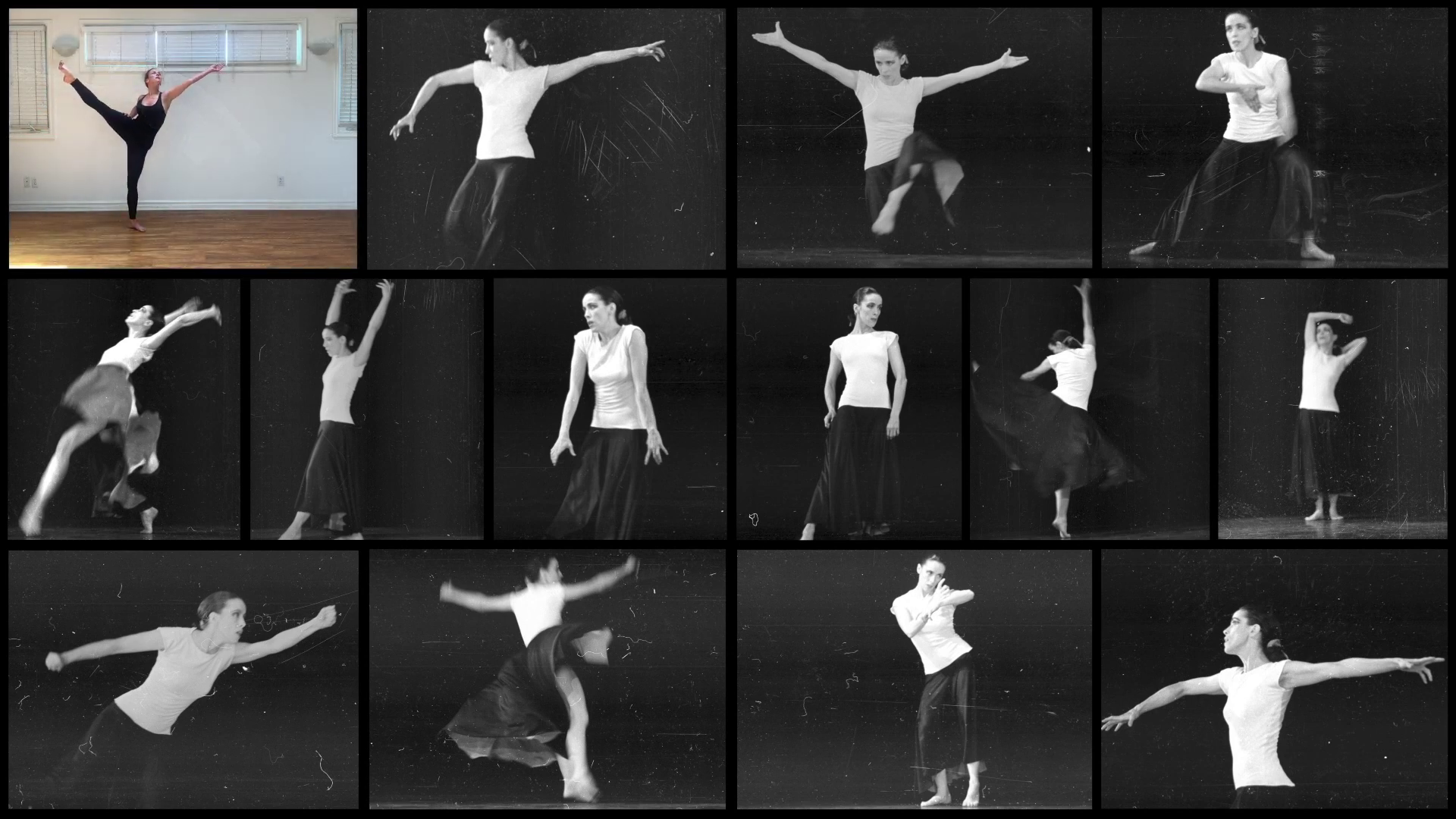

Immediate Tragedy followed a more sinuous path. As Capucilli tells us in a 2014 interview with Leah Clay, in 1988 there was not much information to reconstruct the piece. Unlike Deep Song, there was no substantial archive of photographs for reference, and the possibility of recreating the piece became even more distant after Graham’s death in 1991. All that changed recently, and unexpectedly, when Douglas Fraser contacted the company to explain how his father, Robert Fraser, a photographer, had happened to be sitting in the front row when Martha Graham performed the piece in Bennington in 1937. On June 19, 2020, amidst the height of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, the Martha Graham Dance Company, together with the musicians from Wild Up—under the direction of composer Christopher Rountree—offered a virtual performance of Immediate Tragedy that is available in full on YouTube. (The piece was commissioned by the Younes and Soraya Nazarian Center for the Performing Arts in LA.)

Included in the YouTube video is an illuminating pre-performance dialogue among the show’s creators. The cultural historian and critic Neil Baldwin reads a letter from Graham to Cowell in which Graham speaks about the success of the piece: “I felt in that dance, Immediate Tragedy, that I was dedicating myself anew to space and that in spite of violation, I was upright and that I was going to stay upright at all costs.” Janet Eilber, the company’s artistic director, describes the dance as a dedication to the Spanish women of the era.

As Anna Kisselgoff wrote in 1988 when reflecting on the reconstruction of Deep Song, “A tragedy experienced is not the same as tragedy remembered. Distance has its effect.” The dancer’s embodied knowledge cannot be that of the historic experience. But it was never meant to be. From the very beginning, as the program notes for Deep Song attest, these two pieces were not meant to depict the image of a Spanish woman. They were meant to make visible the embodied experience of history witnessed and brought near—to make history immediate by bringing immediacy to the reality and suffering of the Spanish Civil War. This immediacy was heightened by the circumstances under which the piece was performed in June: the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd.

The reconstructed piece begins by showing a series of boxes, each with a photograph of Martha Graham’s original performance. As the music begins, individual photographs start to dissolve and each dancer, alone, appears inside a frame, unable to meet the other, but with knowledge of the other beyond their frame. Each performs dance phrases inspired by the photographs. Coupled with a score that worked with the impossibility of virtual unison production, and using a system of call and response, the piece unravels before one’s eyes in a series of frames and movements within frames that keep changing in size and duration, while the dancers use Graham’s signature language of contraction and release, extension and fall, spiral, tilts and pitch turns to go through the movements depicted in the photographs.

The frames then move upward, downward, sideways and mark the impossibility of transgressing the limits of space even as space is in continuous transformation through the movement. The dancers’ movements coincide for an ephemeral instant of immediate togetherness. Halfway through the piece, the entire upper rectangle of the screen turns black while, below, rectangular frames of dancers move across in their own frames and disappear to the left. The blackness contains the possible and the impossible, the darkness from where movement and dance are born, where history begins and ends. The dancers appear and disappear as we, as viewers, try to capture movement in its ephemerality. The music accelerates producing a saturation of movement and sound as the frames, now small, move rapidly upward and disappear. Finally, the music slows down, and the dancers all repeat the same standing movement while swaying back and forth, until only the image of Graham, standing, remains. The emotion of the individual performer has become in this performance the passion of a collective identity.

Toward the end of the pre-performance dialogue, Christopher Rountree from WildUp asked Janet Eilber what she thought the piece’s subtitle, “Dance of Dedication,” meant. It referred, she replied, to a moment “when you are committed to a cause—whether it is dance or whether it’s a revolution.” Graham, she added, “was creating a revolution.” Eilber’s reflection invites a new reading of both Deep Song and Immediate Tragedy, in which the aesthetic meets the political—where the demands of history, to which Graham willingly responded, coincide with the development of a new language of dance. I, for one, will never think of a contraction quite the same way again.

Lourdes Dávila, the managing editor of NYU’s Esferas, is a Clinical Professor of Latin American Literature and Culture in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at NYU. She worked for many years as a professional dancer for the companies of Joyce Trisler, Lucinda Childs and David Gordon.