From Fundraisers to the Blacklist: Hollywood and the Republican Cause

After the outbreak of the Civil War in July 1936, not a week went by in Hollywood without a fundraiser for the Republican cause. The film colony was passionately on the side of the Loyalists—a position for which many paid a price in the years of McCarthyism. A look back on a remarkable chapter in movie history.

After the outbreak of the Civil War in July 1936, not a week went by in Hollywood without a fundraiser for the Republican cause. The film colony was passionately on the side of the Loyalists—a position for which many paid a price in the years of McCarthyism. A look back on a remarkable chapter in movie history.

When the actor-director José Ferrer was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1951, he was repeatedly questioned about his support for the Republican cause in Spain. Did he give a speech at a fund-raising event for the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee in 1944? Did he appear on behalf of the Spanish Refugee Appeal in 1945? Was he a sponsor of the American Committee for Spanish Freedom in 1946? And, pressed the counsel, Frank Tavenner, “Weren’t you aware of the Communist Party infiltration into these organizations?”

Ferrer claimed naïveté, saying “However negligent I may have been, my actions have never been other than anti-Communist and pro-American…At this point, I have publicly repudiated all Communist links and sympathies.” Nora Sayre in her book about the Hollywood blacklist, Running Time, described the ordeal Ferrer and others experienced as “a ritual of public humiliation.” Ferrer continued to work in Hollywood in the 1950s, memorably starring in Moulin Rouge and The Caine Mutiny. But other actors and writers who unapologetically supported the Spanish anti-fascists faced the likelihood of a blacklist.

Ferrer’s self-abasement speaks volumes about the fear that gripped the nation, and Hollywood in particular, during the Red Scare era, when investigators demanded an accounting for past political involvement. Individuals and groups that continued to support Spanish Civil War veterans and exiles after the end of the war in 1939 became a target for anti-Communist investigators.

If we were watching a Hollywood film, now would be the time for a gauzy screen to indicate a flashback. Just a decade earlier, Hollywood had been a very different place. After the outbreak of the Civil War in July 1936, observers noted that not a week went by in the film colony without a fundraiser for the Republican cause. Screenwriter Salka Viertel, whose Santa Monica home became a leading gathering place for European emigrés, described the scene: “With the exception of a few calcified reactionaries, Hollywood was passionately on the side of the Loyalists.”

As Larry Ceplair and Ken Englund write in their history The Inquisition in Hollywood, “the Depression, the New Deal, labor strife, the influx of European refugees, and the growth of homegrown fascism “formed a combustible mass, and when struck by international events, blazed forth with Hollywood anti-fascist rhetoric and action.”

Liberals and Communists in Hollywood were united in a display of “Popular Front” solidarity. Groups like Dr. Edward Barsky’s North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, which provided medical aid, found eager supporters. Screenwriter Bernard Vorhaus and his wife Hetty Davies produced a nightly current events radio show on KFPW, highlighting the war in Spain. Screenwriter Mary McCall (herself a liberal anti-Communist) complained jokingly in 1937 that “nobody goes to anybody’s house any more to sit and talk and have fun. There’s a master of ceremonies and a collection basket, because there are no gatherings any more except in a good cause.”

With military aid prohibited by the Neutrality Act of 1936, fundraising in Hollywood centered on ambulances, medical supplies, food, and clothing. One memorable event was a fundraising tour by the French author and aviator André Malraux. At Salka Viertel’s house, “Malraux urgently and passionately asked for help for the heroic struggle of the Loyalists and told about the great support Franco was getting from Hitler and Mussolini … His speech made such an impression that my guests contributed around five thousand dollars”—an amount that comes to roughly $90,000 today.

Hemingway with Joris Ivens and Ludwig Renn in Spain, 1936. Bundesarchiv Bild 183-84600-0001, CC BY-SA 3.0.

An even bigger event was a stop by Ernest Hemingway, traveling with the Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens, whose film The Spanish Earth was narrated by Hemingway. Hemingway headed a group, which included writers Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker, Archibald MacLeish and John Dos Passos, called “Contemporary Historians, Inc.” that financed the film. Hemingway promised that each thousand dollars the film raised would go towards buying ambulances for the Republican forces. On July 12, 1937, three thousand Angelenos, many in the film industry, saw the film and heard Hemingway speak, raising several thousand dollars. However, none of Hemingway’s well-connected friends in the film industry could persuade the studio heads, fearful of controversy, to make The Spanish Earth available for general audiences.

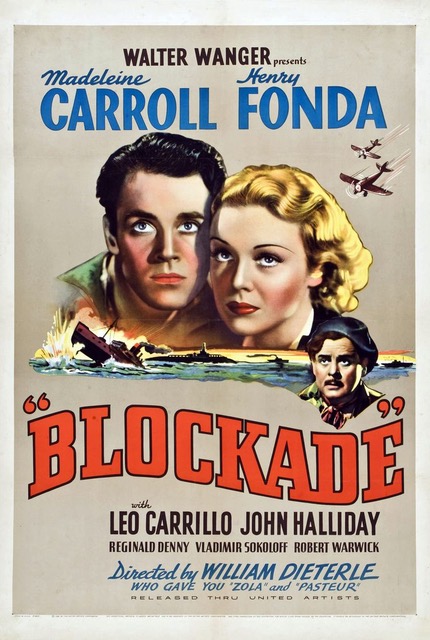

A breakthrough of sorts came in 1938, when a script by John Howard Lawson was turned into the film Blockade. Henry Fonda had the role of a Spanish peasant whose town is threatened by indiscriminate bombing. While in production, the film was attacked by the pro-Franco Catholic Church and the final product was inevitably watered down by Hollywood to the point where the sides in the conflict were not identified by name. Otis Ferguson, the film reviewer of The New Republic, gave an accurate summation of the film’s problem: “Although it is always possible that the right company could make a good fiction-picture out of current affairs in Spain, the odds against are too infinite to monkey with. … If they make a film on anything like Spain, they have to make it mostly hokum or just in fun.” Lawson, in later years, reluctantly agreed with Ferguson’s assessment.

“The possibility that things might go bad for the Loyalists was unthinkable, unbearable,” the actress Karen Morley said, looking back in a 1995 interview. But Franco’s forces were victorious in March 1939, and some in the film community continued to support groups like Dr. Edward Barsky’s new organization, the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC), which was dedicated to “the rescue and relief of thousands of anti-fascist fighters trapped in Vichy, France, and North Africa.” Dorothy Parker became the group’s most active fundraiser in Hollywood. Although Parker is known today mainly for her witty epigrams at New York City’s “Algonquin Round Table” and her humorous poems, she had been a well-paid screenwriter in Hollywood during the 1930’s, writing the script for the original version of A Star is Born.

With the onset of post-World War II anti-communist frenzy, groups like the JAFRC and the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB) were targeted for being, in the phrase of the time, “premature antifascists.” Phillip Deery, in his book Red Apple: Communism and Anti-Communism in Cold War New York, theorizes that Lincoln Brigade fighters who had returned to the United States were singled out by government agencies because, unlike many Communist Party members, the veterans had actual battlefield experience.

Then, in October 1947, the Hollywood blacklist began after the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in Washington D.C. investigated alleged Communist influence in the film industry. All the members of what became known as the “Hollywood Ten” or the “Unfriendly Ten” had been supporters of the Republicans. Two of the Ten were writers with a direct link to Spain: Ring Lardner Jr., whose brother James was killed in 1938 at the Ebro Offensive, and Lincoln Brigade veteran Alvah Bessie, whose book Men in Battle is still considered one of the finest eyewitness accounts of the war. Bessie had gone to Hollywood upon returning from Spain; his original story for Objective Burma, starring Errol Flynn, had earned him a 1945 Oscar nomination.

At the HUAC hearings, none of the “Ten” were allowed to read their opening statements, setting the stage for hostile exchanges between the Committee and the witnesses; only Bessie was able to get as far as his second paragraph before he was shut down. His full written statement put his Spanish experience in context: “In calling me from my home, this body hopes to rake over the smoldering embers of the war that was fought in Spain from 1936 to 1939. … I want it on the record at this point that I not only supported the Spanish Republic, but that it was my high privilege and the greatest honor I have ever enjoyed, to have been a volunteer soldier in the ranks of the International Brigades throughout 1938.”

Once the Hollywood Ten had exhausted their appeals and went to prison for contempt of Congress, the blacklist reached into all corners of the film industry. An informal—and highly profitable—“clearance” industry emerged in 1950, when three former F.B.I. agents began publishing Counterattack: The Newsletter of Facts to Combat Communism. Their handbook, Red Channels, was required reading for executives in film, radio, and television, who were fearful of hiring a performer whose participation would be the subject of protests or boycotts. A suspect actor or actress could gain re-employment, but only for a certain fee, a public disavowal of previous political stands, and a willingness to “name names” before an investigating committee.

A glance through Red Channels reveals that participation in events for VALB or JAFRC was a certain indicator of the threat of blacklisting—as it was for José Ferrer. Dorothy Parker’s entry, for example, goes back to 1938, when she was a sponsor of American Relief Ships for Spain, the Coordinating Committee to Lift the Embargo, and the Medical Bureau and Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy. She was also listed for being a sponsor of the ALBA Fund Drive for Disabled Vets, and a speaker at a 1948 rally for the Spanish Refugee Appeal. Other performers cited in Red Channels for appearing at VALB or JAFRC events were Morris Carnovsky, John Garfield, Howard da Silva, Karen Morley, Sam Jaffe, and Zero Mostel.

Dr. Edward Barsky, whose various organizations had so much support in Hollywood years earlier, ultimately served six months in prison for refusing to share JAFRC’s membership rolls with Congressional investigators. Howard Fast, a celebrated author and JAFRC board member, was also sentenced to three months in prison, where he began writing what was to be his most well-known book, Spartacus. In a piece of delicious irony, Kirk Douglas’ production of the film version of Spartacus (with the blacklisted Dalton Trumbo receiving a screenwriting credit) became a key event in breaking the blacklist a decade later.

Alvah Bessie served a year in prison for refusing to answer questions at the HUAC hearings, and, save for one script written under a pseudonym, never wrote for Hollywood films again. Just eleven years separated the outbreak of the Civil War from Bessie’s appearance before HUAC. As Popular Front enthusiasm gave way to post-war fear, hundreds in the film industry who had passionately supported the Republican cause found themselves unemployable. Veterans of the political struggles connected to the Spanish Civil War can attest that this political chill—and not just in Hollywood—lasted well beyond the Red Scare.

Rick Winston is a film historian living in Adamant, Vermont. He is the author of Red Scare in the Green Mountains: Vermont in the McCarthy Era 1946-1960.

Thank you for this informative article. With each generation the torch is passed to remain vigilant against forces of hatred and politics of fear. Here’s my testimonial for the times we are living now. White Sheets In The White House: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oTKhq6Z9ABE Thanks for all you do

[…] Running guns in Ethiopia would have violated America’s Neutrality Act, passed in 1935, which forbade the “export of arms, ammunition, and implements of war to belligerent nations.” Violators faced fines of up to $10,000 and/or five years in jail. As for Rick’s time in Spain, it is most likely that he worked for a volunteer group like the Lincoln Battalion, who fought against General Franco’s Nazi-backed forces. This would have also violated the neutrality law, although in practice the U.S. government chose not to prosecute volunteers because the public were against it. Either way, life was made difficult for American veterans of the Spanish Civil War, some of whom were later blacklisted by the House of Un-American Activities Committee and generally persecuted as communists (via ALBA). […]

[…] Running guns in Ethiopia would have violated America’s Neutrality Act, passed in 1935, which forbade the “export of arms, ammunition, and implements of war to belligerent nations.” Violators faced fines of up to $10,000 and/or five years in jail. As for Rick’s time in Spain, it is most likely that he worked for a volunteer group like the Lincoln Battalion, who fought against General Franco’s Nazi-backed forces. This would have also violated the neutrality law, although in practice the U.S. government chose not to prosecute volunteers because the public were against it. Either way, life was made difficult for American veterans of the Spanish Civil War, some of whom were later blacklisted by the House of Un-American Activities Committee and generally persecuted as communists (via ALBA). […]