Racial Justice, Then and Now: Paul Robeson’s Antifascist Legacy

Robeson in the 1940’s. Photo by Gordon Parks. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, LC-USF34-013362-C.

Paul Robeson’s anti-fascist activism sought full freedom for oppressed people around the world. The singer consistently spoke against segregation and racial violence in the U.S. as well as colonialism in Africa. Anti-fascism impugns white supremacy, then and now.

As police violence against Black Americans has sparked protests around the country, the term anti-fascism has returned to the headlines. But rather than confronting the reality of institutionalized white supremacy, some on the political right prefer to fuel fear for a loose coalition called “antifa,” which Stanislav Vysotsky has described as a “decentralized collection of individual activists” who use “mostly nonviolent methods” and define fascism as “the violent enactment and enforcement of biological and social inequalities between people.”

Anti-fascism, which has long had an uneasy relationship with mainstream politics in the United States, has been historically important in the fight for racial justice in this country. The Black artist/activist Paul Robeson, for example, formed an independent anti-fascist viewpoint that was grounded in full freedom for oppressed people around the world. He consistently spoke against segregation and racial violence in the U.S. as well as colonialism in Africa. Anti-fascism, in Robeson’s view, impugns white supremacy, the system that helps secure most of the country’s power and wealth in the hands of the few.

Much as the political right today evokes anti-fascism as a supposed threat to take attention away from anti-racist protests, in the post-World War II years, anti-communist hysteria and fear of anti-fascists, served to distract attention from racial injustice. Portraying anti-fascists as part the communist “menace” obscured their role as supporters in the struggle against race discrimination.

In a 1950 speech, Robeson clarified where the root of the problem lay. What is the greatest “menace” in the lives of African Americans? he asked the audience. “Ask the weeping mother whose son is the latest victim of police brutality.” The menace, he said, are not anti-fascists or communists, but “white supremacy and all its vile works.”

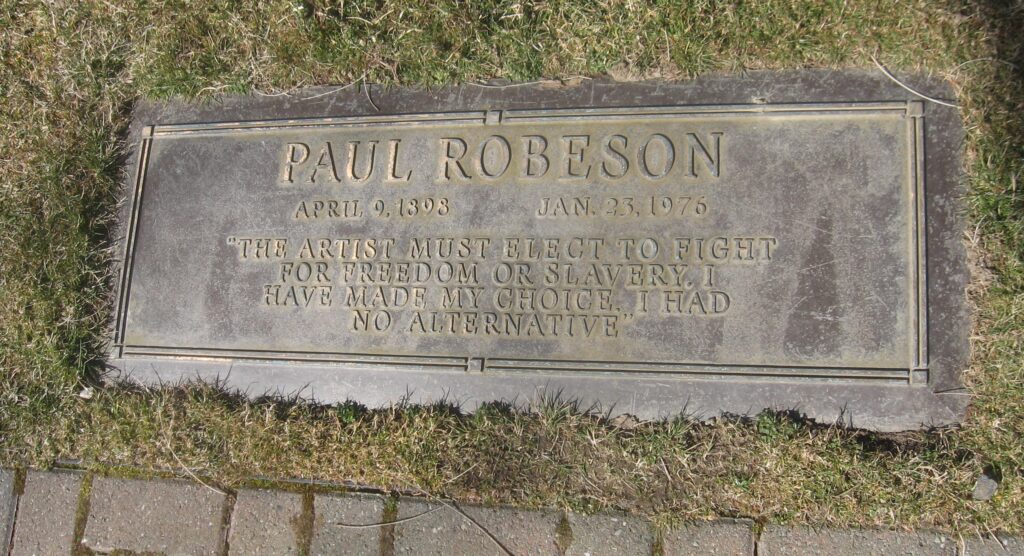

Robeson’s grave at Ferncliff cemetery in Hartsdale, NY is engraved with part of his 1937 speech. Photo by author.

Robeson’s anti-fascism had reached maturity by the 1950s, but it was the Spanish Civil War that helped solidify his perspective. A world-famous vocalist and actor by the 1930s, Robeson spent much of that decade performing and making films in the U.K., Europe, and Soviet Union. In 1934, he had an encounter with Nazi soldiers in a train station that confronted him with the climate of “hatred, fear and suspicion” that was fueled by fascism. By 1937, his anti-fascism coalesced around the war in Spain. At a rally for Spanish refugees in London, Robeson delivered what became one of the most iconic speeches of his career. He argued passionately against fascism and pointed out that “because fascism fights to destroy the culture which society has created” the artist “cannot hold himself aloof” from the conflict. “The artist must take sides” in the fight for freedom over slavery. “I have made my choice,” Robeson affirmed, “I had no alternative.” This speech signaled a turning point in Robeson’s career. Afterward, he publicly wedded his anti-fascist politics with his artistic career and used his celebrity as a platform for social justice advocacy.

The next year, Robeson traveled to Spain and sang for soldiers near the front lines. (This visit has been well documented in The Volunteer, June 2009.) He was moved by the commitment of the international volunteers in Spain, especially the African Americans he met. He also learned about the Black commander of the battalion, Oliver Law, whom he hoped to one day honor in film. In an interview, Robeson clarified that his support for the Spanish anti-fascist cause stemmed, in part, from his racial heritage. “I belong to an oppressed race,” he said, “discriminated against, one that could not live if fascism triumphed in the world.” Fascism was a threat not only as a destroyer of culture, but also as a spreader of the false idea of racial superiority. “My father was a slave,” he added, “and I do not want my children to become slaves.”

In 1939, as World War II commenced, Robeson returned to the United States. Once the nation officially joined the global war against fascism, following Pearl Harbor, anti-fascism became a widely embraced political position. Activists in the Black community advocated a broad interpretation of anti-fascism that was sometimes referred to as the “Double Victory”: not only over Axis powers but also over segregation at home. Robeson’s anti-fascism went a step further, adding the dismantling of Western colonialism—ending all forms of race discrimination.

Robeson worked tirelessly for the war effort in the early 1940s at war bond rallies and even performing in the first desegregated U.S.O. show for troops. In a 1943 speech, he stressed that African Americans must view their struggle for rights as part of the “global struggle against fascism.” In another speech that year, he connected African Americans with the colonized peoples in Africa, noting that “their freedom is our freedom.” He closed a speech on Black Americans by stressing that “we recognize the fact that our enemies are not only Germany, Italy and Japan; they are all the forces of oppression, intolerance, insecurity and injustice ….” His comprehensive understanding of anti-fascism was a reminder that Germany was not the only country with policies of racial supremacy.

Robeson maintained his anti-fascism even as U.S. politics began to portray communism, not fascism, as the greatest threat to democracy. Racial violence increased after WWII but was often ignored as anti-communist hysteria gripped the nation. Robeson, incensed that Black veterans were being lynched, led a delegation to speak with President Harry Truman in 1946. But the president replied that it was not politically expedient to act against lynching. When, at a press conference following the meeting, Robeson was asked about his political affiliation, he described himself as an anti-fascist, noting that he had “opposed Fascism in other countries and saw no reason why he should not oppose Fascism in the United States.” That same year, when he testified before a California committee on Un-American Activities, Robeson once again characterized his politics as “anti-Fascist and independent.”

In 1956, Robeson was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). By then he had lived through a decade of blacklisting and repression because of his political advocacy. The tone of that testimony was more charged then ten years before. When the committee asked why he did not simply move to Russia or another country, Robeson shot back: “Because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here and have a part of it just like you. And no Fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?” The committee tried to trap Robeson, but he turned the discussion back to racial justice and anti-fascism. Robeson, knowing that the HUAC had been formed by segregationist Democrats like John Rankin and had refused to investigate KKK violence, kept the issue of race at the heart of his testimony, not allowing it to be diluted by anti-communist probing.

The antifa hysteria today fuels fears of violence against white property. New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof noted in June 2020 that “antifa panics are where racism and hysteria intersect.” Much in the same way, in the 1950s hysteria was fueled by stoking fears of communist infiltration and casting civil rights activists as communist agitators. Rather than examining racism, people focused on an internal communist menace that never materialized. Today, the perceived threat of antifa prevent some from addressing problems of police brutality and systemic racism. Or worse, as Mark Bray warns, “the allegation that destruction is being wrought by antifa threatens to expand government and police repression to everyone out on the streets.” We should, like Robeson, remember the connection between anti-fascism and racial justice and not be deterred in the fight against the long-standing foe: white supremacy.

Lindsey Swindall teaches at Stevens Institute of Technology. She is the author of Paul Robeson: A Life of Activism and Art and The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World: Southern Civil Rights and Anticolonialism, 1937-1955.

This is a fascinating, inspiring piece on the roots of the modern Black Lives Matter and antiracist movements. Thanks!