Gota de Leche: Quakers in the Spanish Civil War

In the summer of 1937, Esther Farquhar, an Ohio Quaker recruited by American Friends Service Committee, arrived in Murcia to organize the feeding of the starving refugees. A photo diary discovered in the archives inspired the author to join humanitarian relief efforts happening today. “If they were able to do so much with so few resources, might I not be able to help refugees as well?”

The summer of 2017 was a period of rest and reflection for me, and I chose to take a month’s sabbatical at Pendle Hill, the Quaker retreat center in Wallingford, Pennsylvania. Unlike most people who stay at Pendle Hill for an extended period to work on a project, I arrived without one. I slipped into the daily routine of morning meeting for worship, meals, and loafing, allowing for Spirit to lead me in a new direction.

The library was my favorite spot. It is situated on the ground floor of Pendle Hill’s newest dormitory, and its tall windows look out on the lawn and the center’s vegetable garden. I recalled times spent in libraries as a child, when I would walk to the local library to escape the summer heat and boredom, spending hours reading anything that attracted my curiosity.

The library was my favorite spot. It is situated on the ground floor of Pendle Hill’s newest dormitory, and its tall windows look out on the lawn and the center’s vegetable garden. I recalled times spent in libraries as a child, when I would walk to the local library to escape the summer heat and boredom, spending hours reading anything that attracted my curiosity.

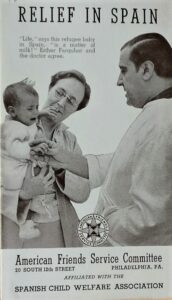

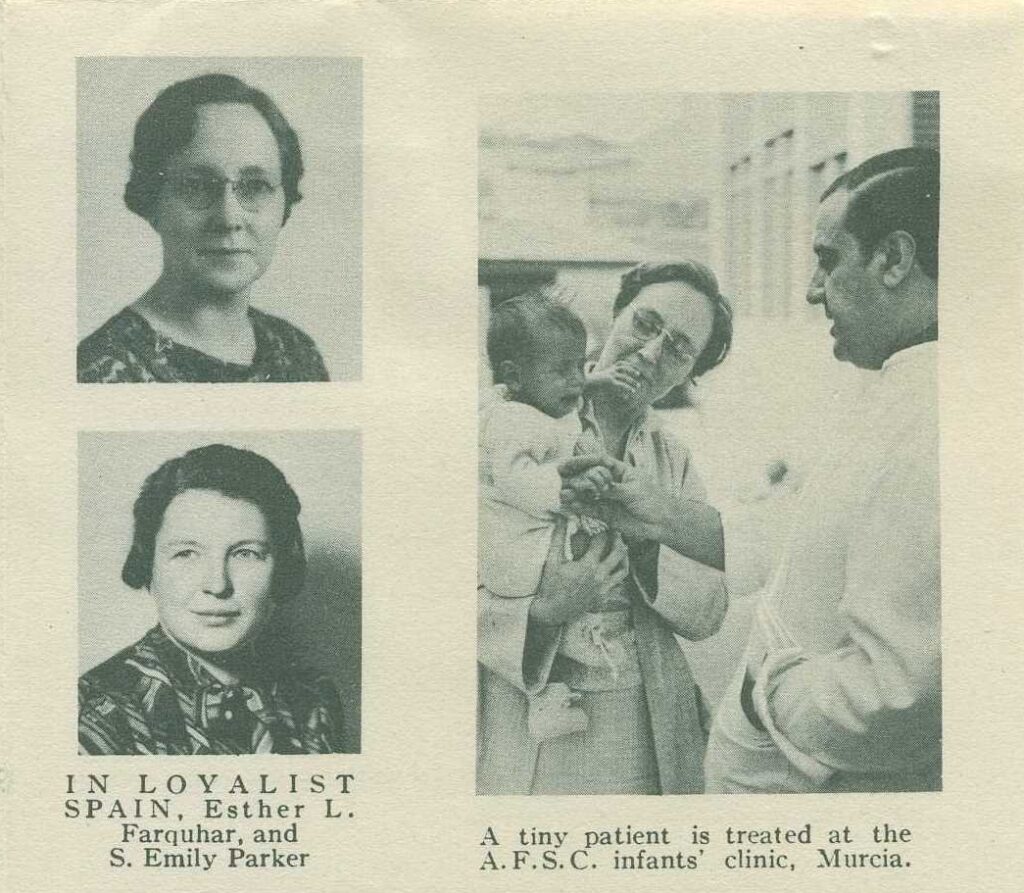

One day a shelf of books bound in green with gold embossed lettering caught my eye. Organized by year, they contained the leaflets and booklets published by American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). In the volume of literature pertaining to the Spanish Civil War, a picture of a middle‐aged woman holding a crying child next to a man dressed in white caught my eye. The caption read: “‘Life,’ says this refugee baby in Spain, ‘is a matter of milk!’ Esther Farquhar and the doctor agree.”

The woman was dressed in a linen suit in the style of the late ’30s. She wore her hair in a plain side part and had large rimless spectacles. She looked more like a schoolmarm than a nurse, yet her concern for the child was unmistakable. Intrigued, I flipped through the pages of the 1937 section of the journal for clues to her identity.

Another pamphlet titled Relief in Spain featured the same photo on the cover. Inside was a picture of a malnourished infant lying on its back in a crib. The caption said the picture was taken in the Friends Hospital in Murcia, Spain.

In early 1937, the combined Fascist forces of Franco and Mussolini mounted an offensive on Malaga, in the south of Spain, then the main location of the anti‐Fascist Republican army. The attack left thousands of pro‐democracy Republicans dead. The Republican women, children, and elderly fled north and east along the coastal road toward Almeria, and then further to Murcia.

Franco’s army chased the fleeing people by air, shelling the column of refugees like an angry child stepping on a line of ants. This bloody exodus is known in Spanish history as the Caravan of Death. Half‐ starving, the refugees who survived the slaughter arrived in Almeria and Murcia, 250 miles from Malaga, with nothing but the clothing on their backs.

Murcia, a small city in a region of eastern Spain, lay in the area defended by the Spanish Republicans. Most of the refugees took up long‐term residence in abandoned buildings in squalid conditions in the region, relying on rations from relief centers or hospitals for their food.

A joint relief effort of American and British Friends and Mennonites undertaken during the escalating Spanish Civil War was centered in Murcia. The area of relief, known as the “American Quaker Sector,” covered about 200 miles of coast from Alicante to Murcia and extended about 45 miles inland, according to Gabriel Pretus in Humanitarian Relief in the Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939.

It was in Murcia that Esther Farquhar, an Ohio Friend recruited by AFSC, arrived in June 1937, shortly after the joint relief effort was begun, to organize the feeding of the starving refugees. Farquhar had taught Spanish at Wilmington College in Ohio, after working for a time in a Friends school in Cuba. She had also worked in Cleveland, Ohio, as a social worker. Her professional background made her a good candidate for the work, but it was her even‐handed approach with the refugees, multi‐national relief workers, and the Spanish officials that gained respect for the relief work of the Friends and Mennonites and made it so effective.

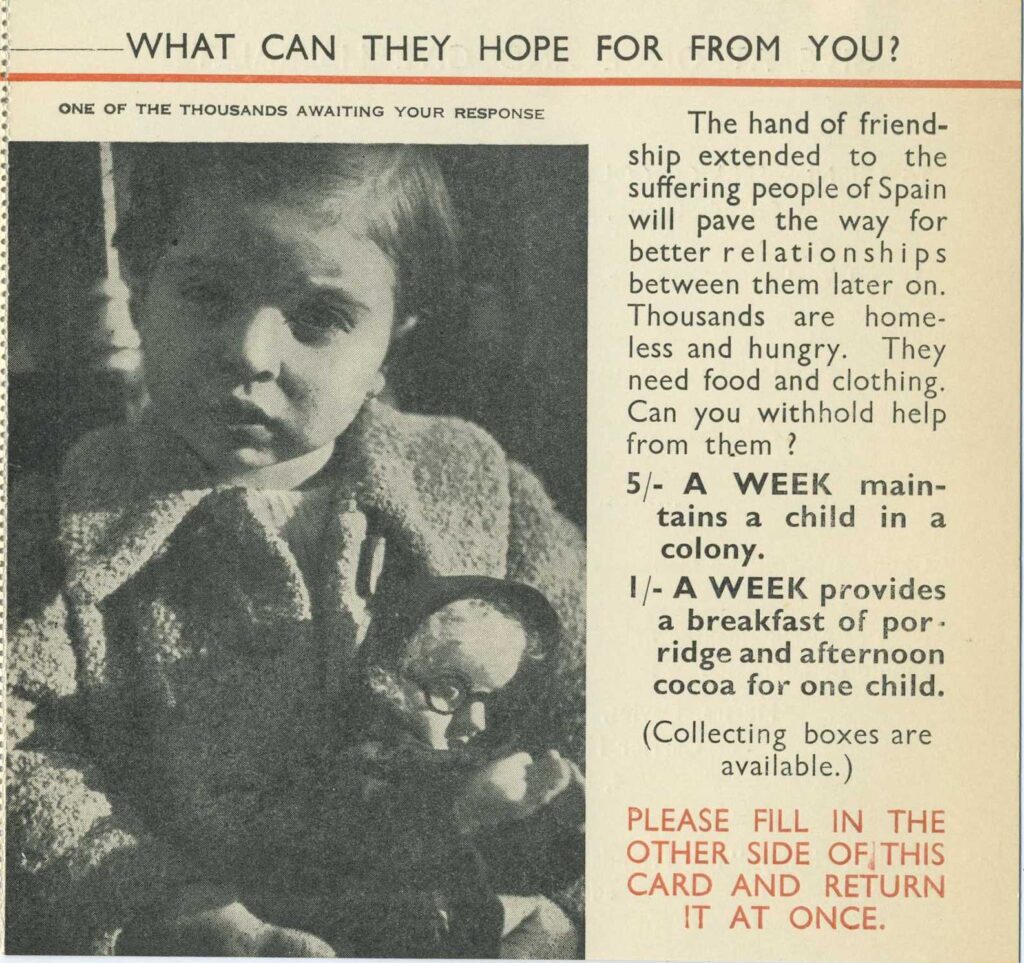

Once in Murcia, Farquhar saw an immediate need for extra nourishment for the youngest refugee children. The standard ration up to that time was a small amount of bread per day, hardly enough for a baby to grow on. The youngest children showed signs of malnutrition.

Gota de Leche (Drop of Milk), as the milk centers for infants and small children were named, was Farquhar’s passion. She imagined the milk centers as places where mothers could get enough milk each day to supplement either breastfeeding or solid food. This might prevent malnutrition, rickets, and death.

Fortunately, the head of the Friends Committee on Spain, John Reich, was supportive of her plan. Farquhar sent a cable to the Swiss organization Save the Children asking for 200 cases of either fresh or condensed milk to be shipped to her as quickly as possible. They responded immediately with the shipment of milk to Murcia. The first Gota de Leche was on its way. Others were added in cities where the Friends had refugee feeding stations.

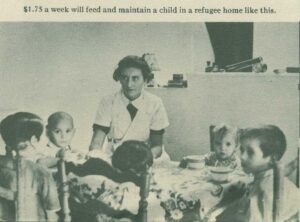

If diplomacy was Farquhar’s strength, paperwork was her weakness, so it is difficult to tally exactly how many children received nourishment through Gota de Leche. An excerpt from a cable dated December 27, 1938 in the AFSC Archives in Philadelphia, notes that 50,000 children were receiving bread daily, “plus 10,000 in milk canteens under direct Quaker administration.”

The selective and at times ad hoc nature of the relief feeding efforts was dictated by the small staff and intermittent flow of supplies into the region from Europe and the United States. The nonpartisan stance of AFSC, and the success of relief efforts in Germany and Austria after WWI, made it possible to serve Spanish civilians in both the Republican and Fascist regions of the country from 1937 to 1939.

Esther Farquhar worked in Murcia only one year until her health failed her and she was forced to return home. Her work, continued by others, was deemed a critical necessity for the survival of thousands of refugee children in Republican Spain.

An AFSC report on the work says:

After a year of single‐handed responsibility for the hospitals, feeding centers and other refugee aids in Southern Spain, Esther Farquhar returned home in June 1938. Her rare tact and sympathy won the lasting affection of the Spanish people and laid a firm foundation of the continued work of Clyde E. Roberts; Emily Parker; Alfred H. and Ruth B. Cope; Florence Conard; and representing the Church of the Brethren, Martha Rupel.

My fascination with Farquhar and AFSC relief work led me to the AFSC Archives at Friends Center in Philadelphia one afternoon before the end of my Pendle Hill retreat. There I found the photo diary of Emily Parker, a young AFSC worker who assisted Farquhar in Murcia. Bent and aging sepia snapshots in an old, deerskin‐covered album showed a woman dressed in white with schoolmarm hair and glasses holding an infant in her lap.

Written in ink next to it were the words, “Baby born on Malaga Road during flight from that city. In picture is 18‐month‐old and weighed slightly under 10 pounds.” Just below it, another snapshot without description showed the same woman cradling the child and feeding it a bottle of milk.

I was profoundly impressed by what I learned of the relief effort mounted by this small group of dedicated American and British faith workers. If they were able to do so much with so few resources, might I not be able to help refugees as well?

My research on refugee relief through the Internet and social media led me to a small, informal non‐governmental organization (NGO) in Turkey that posted a request for volunteers online. Ironically, the group is also led by a middle‐aged woman who, through a passion for service, founded Team International Assistance for Integration (TIAFI). Run by volunteers, the group has created a community center where vulnerable Syrian refugee women and children receive daily meals, language instruction, and job training in order to begin new lives in Turkey.

Through email and Skype, I was able to make contact with TIAFI’s volunteer coordinator. We agreed that if I came to work at their community center, my skills would be put to use. With Turkish tourist visa in hand, I left for Europe in October, planning to travel from the United States to Rome to Izmir, Turkey, for several weeks of volunteering. But once I arrived in Italy, I learned that the Turkish government revoked all tourist visas for American citizens as a result of an escalating dispute between the two governments.

Instead, I sent TIAFI a donation of what amounted to my round‐trip plane fare from Rome to Turkey. With my donation they purchased a heating stove for their center just as the weather turned cold. I am now working remotely with their volunteer coordinator to support their social media and marketing efforts.

Backpacks and purses that the Syrian women have been trained to make in TIAFI’s workshop are available for a donation to the group. The Turkish government forbids them to be sold as TIAFI isn’t recognized as a legal entity. This helps the Syrian women to cover some of their living expenses. Hopefully the refugee families will be able to return to Syria once it is safe.

Inspired by the story of Esther Farquhar’s Gota de Leche, I found a sense of agency I’d lacked. I’m now confident in my ability to effect a small change or give relief, where before I felt baffled about how to begin.

The United States and the European Union have almost completely stopped accepting refugees from Syria and Africa because of political backlash. The refugee crisis has grown to epic scale. Many families wait in squalid conditions in Turkey and Greece, unable to officially relocate to a new home and unable to return home. Not since World War II have so many been displaced. The work of Friends in Spain points the way to our power to relieve the suffering of others.

The United States and the European Union have almost completely stopped accepting refugees from Syria and Africa because of political backlash. The refugee crisis has grown to epic scale. Many families wait in squalid conditions in Turkey and Greece, unable to officially relocate to a new home and unable to return home. Not since World War II have so many been displaced. The work of Friends in Spain points the way to our power to relieve the suffering of others.

There are ways each of us can give comfort to refugees. The easiest is by financially supporting the many NGOs working in the region. Some of the larger ones are listed at USAID Center for International Disaster Information’s website: cidi.org/syria-ngos. I found TIAFI through a social media search. Facebook has a number of pages that are a clearinghouse for refugee volunteer activities. Many of the smaller groups welcome students and adult volunteers for short work stays in the refugee camps in Greece, where it’s easy to travel. It is always advisable to thoroughly research an organization before committing time and money.

Camilla Meek lives and works in Durham, North Carolina. She remembers seeing machine gun-armed Franco regime soldiers stationed in front of public buildings while visiting Madrid in the early 1970s. Her early literary influences were Pilar in For Whom the Bell Tolls and Gertrude Stein. For Camilla, writing is a way to bring extraordinary human qualities to light. Special thanks to Don Davis of the AFSC Archives.

What a wonderful story…makes each of us proud, to be a Quaker!

Peace Profound, Jules

Moving and instructive and informative.