Book Review: Leonora Carrington, Down Below

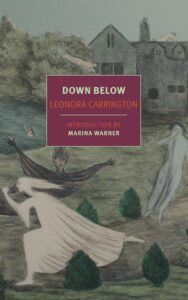

Down Below, by Leonora Carrington. Translated by Victor Llona, with an introduction by Marina Warner. New York: NYRB, 2017. 112 pp.

Down Below, by Leonora Carrington. Translated by Victor Llona, with an introduction by Marina Warner. New York: NYRB, 2017. 112 pp.

Written in 1943 about events that took place between 1940 and 1941, Leonora Carrington’s Down Below offers the compelling testimony of a young woman institutionalized for madness while the world itself seemed to go mad around her. In an account that strives to be “truthful but incomplete,” as she puts it, Carrington (1917-2011) describes her experiences following the internment of her lover, the surrealist painter Max Ernst, in a concentration camp in France shortly before World War II. She details her subsequent escape to Franco’s Spain, her increasing delusions and paranoia, and her 1940 institutionalization in a mental hospital in Santander. While her account clearly shows her brilliance as a writer and artist, it also demonstrates a subtly subversive, feminist interpretation of events by a young woman who has lost control over her environment, her bodily freedom, and even her own perceptions. Eighty years later, it remains a transfixing story of an individual struggle for wellness and reason in the face of overwhelming world events and traumatic personal experiences.

In the late 1930s, as the Spanish Republic was losing the war against Franco and France faced the threat of German aggression, Carrington and Ernst were living in Saint Martin d’Ardèche, near Montélimar in the south of France. The 23-year-old Carrington had already made a name for herself among the surrealists. She’d begun to publish her writing, beginning with The House of Fear (1938), and to find her style as a painter with her Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) (1938) and The Horses of Lord Candlestick (1938), which was purchased by Peggy Guggenheim. This productive period came to an abrupt halt in September 1939, when Ernst was arrested and interned as an “undesirable foreigner.” After Carrington and friends initially succeeded in earning his release from the L’Argentière concentration camp, Ernst’s confinement at Les Milles in May 1940 and the encroaching German invasion were soon followed by Carrington’s break from reason.

Carrington begins her recollections in Down Below following the traumatic moment of Ernst’s second detention. The account traces in chronological order what followed, including her journey with friends to Franco’s Spain, her increasing delusions, the peak of her madness resulting in her institutionalization, and her experiences at the hospital in 1940. Restrained and injected with the convulsion-inducing drug Cardiazol, she experiences not just her physical discomfort but a violation of her bodily autonomy.

Carrington’s delusions are fueled as much by the political and historical context as her anxiety about domination and powerlessness. When Ernst is taken away, the world spins out of control, and her own autonomy is compromised as she loses control over her circumstances and her mind. Her paranoia is rooted in the rise of fascism, the alliance between Franco’s Spain and Nazi Germany, and the patriarchal power structures of the period. Soon after the onset of her psychiatric symptoms, she begins imagining a sinister global network. She is convinced that the Nazis are exerting their influence on Spain and Franco through psychological manipulation. She specifically fixates on a man named Van Ghent, who she knows to be “somehow” associated with the Nazi government. After meeting with the British Consul to tell him that “the World War was being waged hypnotically by a group of people—Hitler and Co.—who were represented in Spain by Van Ghent; that to vanquish him it would suffice to understand his hypnotic power,” Carrington is confined. Her paranoia struggles to make sense of real-world events and power structures that are no less unsettling than her delusions. After all, Spain itself has just emerged from its civil war; just after her arrival, Carrington recalls imagining “that the red earth was the dried blood of the Civil War. I was choked by the dead, by their thick presence in that lacerated countryside.”

Rooted in the social and historical circumstances of its author’s life, Down Below is a disturbingly beautiful exploration of sanity and insanity in a chaotic historical moment. For contemporary readers, it provides a vivid depiction of an individual experience of inner turmoil fueled by a troubled, unpredictable, and dangerous world. What could be a more suitable book for our time?

Camille Meder is a Ph.D. student in the Department of English at Claremont Graduate University who focuses on modernist literature.