Loyalist Voices Crying Out across the Ocean: the EAQ Radio Broadcast during the Spanish Civil War

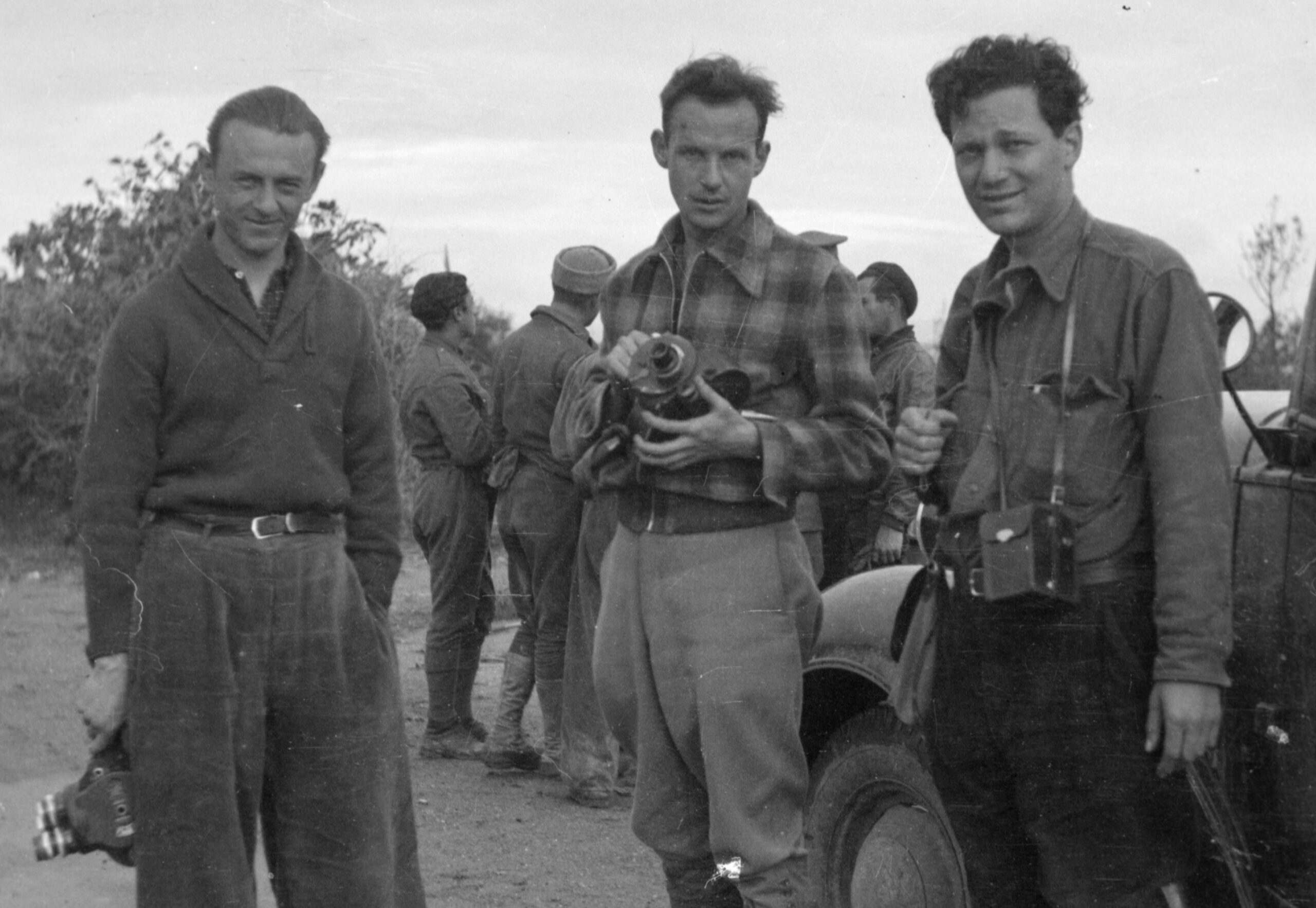

Jacques Lemare, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Herbert Kline. (Tamiment Library, NYU, 15th IB Photo Collection, Photo #11_0818)

In the spring of 1937, a group of English-speaking journalists and filmmakers launched a shortwave radio broadcast from Madrid to tell the world what was happening in Spain firsthand. It found an eager audience all across the United States and Canada.

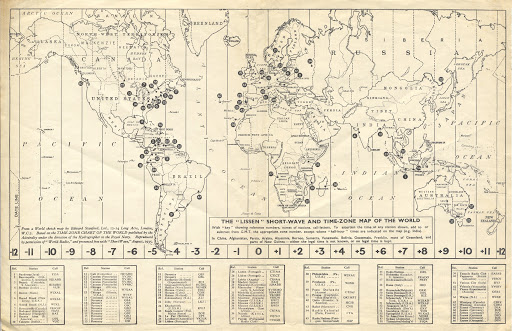

In the age of the internet, it’s easy to forget the power once held by shortwave radio. Thanks to skywave or “skip” propagation, through which radio signals refract off the upper atmosphere, shortwave has an exceptional broadcast range. In the intense political climate of the 1930s, it became part of a global political battlefield. Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy took advantage of shortwave technology to disseminate their messages around the world. But they were not the only ones to use its power to reach distant audiences.

On March 28, 1937, a note from The New York Times read:

Today from Spain the Loyalist voices cry out across the ocean in words such as these that surge through the peaceful Spring air of the American evening:

“Hello, hello, English-speaking friends and listeners; take a walk with us along the deserted streets of Madrid. Hear the dreadful hum of an approaching enemy plane and you rush to cover, there to find terror-stricken women, children, old men and women huddled in fear. There is a terrible detonation, a breaking of glass and a storm of dust; a bomb has struck nearby.”

Orrin E. Dunlap Jr., radio editor at the Times, chronicled the first English-speaking independent broadcast for American listeners eager to know more about the unfolding of the Spanish war and, more specifically, about events taking place on the Republican side. The “Loyalist voice”—the man behind this experimental broadcast and the ones to follow—was Herbert Kline, future director of documentary films such as Heart of Spain (Kline and Geza Karpathi, 1937) and Return to Life (Herbert Kline and Henri Cartier, 1938).

Orrin E. Dunlap Jr., radio editor at the Times, chronicled the first English-speaking independent broadcast for American listeners eager to know more about the unfolding of the Spanish war and, more specifically, about events taking place on the Republican side. The “Loyalist voice”—the man behind this experimental broadcast and the ones to follow—was Herbert Kline, future director of documentary films such as Heart of Spain (Kline and Geza Karpathi, 1937) and Return to Life (Herbert Kline and Henri Cartier, 1938).

Kline had quit his well-paid job in New York as director of the Left Front magazine New Theatre and Film, and turned down several jobs from the publishing world and film industry, to go to Spain. After raiding his own savings and those of his friends and relatives to pay for his trip, he traveled to Madrid, offering his services as a journalist, producer, and writer to the Medical Bureau of the American Friends of the Spanish Democracy (later known as the American Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy). In Spain, Kline organized a network of “Cultural Front” writers, journalists, and filmmakers who worked cooperatively in an Anglo-American news service that sought to provide the liberal and conservative press with news from the Loyalist Spain. None of these writers would be paid for their work.

Their shortwave radio station, EAQ nº 2, reached states such as New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Idaho, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Texas, Ottawa, and Ontario. But, important as the collaboration of the leftist intellectual workers was, the cooperation of the American audience proved critical for helping the initiative get off the ground. Between March 22 and 24, 1937, more than 20 letters from citizens across the US and Canada reached the headquarters of the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy (NACASD) at 381 4th Avenue, New York, and the desk of Edwin Rolfe, a poet and a journalist at the Daily Worker who would join the Lincoln Brigade later that year. All of them contained the same message: their authors confirmed that they’d been able to tune into the experimental EAQ nº 2 broadcast from Madrid on the evening of March 22.

The EAQ shortwave station, which broadcast on 31.565 meters, 9.4 megacycles, was described as an official government station because its infrastructure was provided by the Spanish Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT, the labor union associated with the Socialist Party), whose general secretary at the time was Francisco Largo Caballero. But in practice the EAQ nº 2 always operated independently from the Spanish Government. During the experimental transmission on March 22, Herbert Kline had asked the radio audience for feedback about the quality of the broadcast and sent a special message to the NACASD.

Many of these first listeners were passionate radio hams, and they provided thorough reports concerning the outlets they were using, the weather at the time and place they were listening to the program, references to fading, interferences, and whether they were using a stenographer, shorthand writing, or just taking notes to convey the message. Also, following the request made by Kline, the listeners urged the executive board of the NACASD and Edwin Rolfe to listen to the broadcast with news from Spain to be aired on Friday, March 27. One of them signed his letter as “a sympathizer of the Spanish Loyalists”; another wrote in red ink and capital letters “NO PASARAN” and “MADRID shall be THE TOMB OF THE FASCIST!” One well-informed listener advised: “The program comes in perfect, here QSA5 R9 (no fading, no interference now) but Mussolini will soon have a station right over yours as he did over ETB in Abyssinia (Ethiopia), so you better shoot while the line is clear.” All reports agreed that the broadcast came almost as clear and powerful as a local station—something that was confirmed the following days by the note published in the New York Times: “the EAQ nº 2 is louder than London, louder than Berlin, and these two cities have been the most powerful voices across the sea. Apparently Madrid is pumping tremendous power into its ethereal arteries and has erected a directional aerial that megaphones the broadcasts to the United States and Canada.”

Up to that moment, the American radio audiences only had a chance to follow the news in Spain through major radio broadcasts such as The March of Time, sponsored by Times Inc. Produced and written by Louis and Richard de Rochemont, this very popular newscast staged the news using actors and special effects in order to achieve a dramatic atmosphere that could engage the audience emotionally. For instance, the broadcast of December 31, 1936, dramatized the bombing of a church in Madrid on Christmas Eve. Listeners could hear the priest, the worshippers, and the music in the church—all of them created in a radio studio—while the narrator commented on the event. At some point, he was interrupted by the buzzing of a plane, explosions, and cries of victims (in Latin-American Spanish). Undoubtedly, this immersive way to tell the news was emotionally powerful; but it lacked authenticity. The EAQ nº 2, by contrast (even if marginal compared to big news corporations) provided Canadian and North American radio audiences with the possibility of getting fresh news from the Loyalist side, reported by professional correspondents who were witnessing the events they conveyed to the audience. They did not use special effects: their voices were the most powerful weapon to convey emotion, because they were the voices of committed reporters who had experienced the events they were describing. On April 2, 1937, Kline addressed the audience in first person to say:

No pasaran! still stands. What is not known that should be of the greatest concern to all American listeners is the human cost behind this good news.

For the past few weeks I have spent most of my time with the Hispano-Canadian blood Transfusion Service. It has been my job to work with them writing a scenario and co-directing a film. In this film work I have witnessed the human cost behind the welcome news which the outside world has heard against the fascist offensive …

After describing the dreadful effects of the bombings on the Spanish population, he finished his long speech with a thorough report on the medical needs of Madrid and those of the Canadian and North American professionals working for the Medical Bureau, led by Dr. Norman Bethune and Dr. Edward K. Barsky.

Kline’s reports show that the EAQ was more than a radio broadcast. It also served as a channel of communication for people volunteering in Spain (Kline, Barsky, Bethune, and their collaborators) and the people of the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy in the US, who used the broadcasts to raise awareness about the situation in the Loyalist Spain, to ask for aid and supplies, and to inform the relatives of their correspondents.

Following the note at the Times, in fact, Francis A. Henson, the director of the National Campaign at the Medical Bureau wrote to Varian Fry (from the NACASD) suggesting that he advertise the broadcasts and arrange for cable for the broadcasters to make more specific appeals for clothes, food and medical supplies, even mentioning the NACASD. This method of getting supplies had been successfully used in the Ohio River Great Flood earlier in January that year, when 385 people died, and one million people were left homeless. Accordingly, the Medical Bureau devised a strategy to reach the American public, publicize the Bureau’s work, and raise support among the citizenry.

In a letter sent from the Medical Bureau to the NACASD on April 7, 1937, the Bureau included the schedules of the EAQ special program and information broadcast for USA and Canada from Madrid, in English (which at that time was aired every Tuesday and Friday, from about 7.30 to 9.30pm). The letter also said that they acknowledged cables received from US and Canada at 9 pm. Following this information, the Medical Bureau suggested making sure that once a week, either a member of their hospital, or a communique, could be sent over for five minutes in order to officially convey the requests of the hospital, including specific supplies and specialized personnel. At the suggestion of the Medical Bureau, Edward Barsky, the head of the American medical services in the Loyalist Spain, approached the radio station on a weekly basis in order to pass on official requests for supplies and personnel. The solidarity of the American public with the Spanish Republic was thus sustained, among other channels, by the committed, informative, and moving speeches by Barsky and Kline broadcast through shortwave radio.

Sonia García López teaches at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. She is the autor of Spain is US. La guerra civil española y el cine del Popular Front: 1936-1939.