Hubs of Antifascism: The Spanish Anarchist Press in the United States

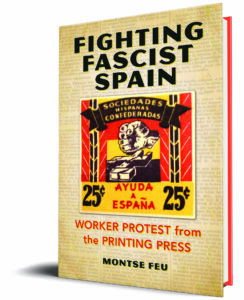

Stamps to raise funds for the Spanish Republic from the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas. Courtesy of Montse Feu/Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Project.

Among the thousands of Spanish workers who arrived in the United States around the turn of the twentieth century were many with radical traditions rooted in their homeland, which at the time boasted one of the world’s most vibrant anarchist movements. They created scores of cultural and mutual aid societies in cities and rural and mining areas across the United States, fueling anti-authoritarian and emancipatory practices that foregrounded the creation of culture from below. During and after the Spanish Civil War, they also built support networks for refugees and published periodicals that reported on the war and denounced Francoist repression.

Print culture was central to the anarchist movement. From 1880 to 1940, about 235 anarchist periodicals circulated in the United States, and about 850 in Spain. Some of these periodicals were ephemeral, while others lasted decades and published thousands of issues. Despite the irregularity inherent to the alternative press, workers’ periodicals constituted a reliable source of news, opinion, ideas and practices. They also operated as connecting hubs for anarchist networks in the United States, as their editors and staff became organic leaders of the anarchist movement. For many decades, anarchist newspapers and magazines functioned as effective resources to contest elitism and repression while fostering grassroots solidarity and mutual aid in the heterogeneous and decentered cultures of the US anarchist movement.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out, anarchist groups and their newspapers supported antifascist efforts from the United States. The largest Spanish-language periodical, Cultura Proletaria, along with the CNT-FAI, a confederation of anarcho-syndicalist unions and affinity groups, founded the United Libertarian Organizations (ULO). The ULO’s main activity was the publication of the periodical Spanish Revolution (1936-1938). It underscored the achievements of the workers’ revolution in Spain—until, that is, the CNT-FAI decided to join the Spanish Republican government during the war. As in Spain, the episode was a sore point of controversy among anarchists in the USA, some of whom garrisoned orthodox purity while others conceived state cooperation as the lesser evil, acceptable in light of the urgency of the struggle against fascism.

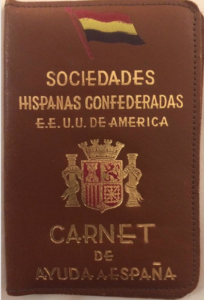

José Nieto’s membership card of the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas. Courtesy of Montse Feu/Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Project.

Other U.S.-based anarchists also joined to support the Spanish Republic. Historian Kenyon Zimmer has counted approximately 100 anarchists who joined the International Brigades and fought in battle. Meanwhile, contributors to communist and anarchist periodicals in the Americas travelled to Spain to report on the war. Among them were the Cuban Pablo de la Torriente Brau and Luis Zugadi Garmendia, who was of Basque origin. Both died in battle in Spain.

Another significant US-based effort to support the Spanish workers started only eight days after the uprising of Francisco Franco, when about 200 U.S. Hispanic cultural and mutual aid societies came together in what became known as the Sociedades Hispanas Confederadas (SHC, Confederation of Hispanic Societies). Although the SHC grew to 65,000 members at its height, it maintained close ties with anarchist and socialist networks, which often shared their membership. These links would later be vital for the relocation of refugees from Spain. This was the case of José Nieto Ruiz, who escaped Spain after being subjected to torture for his syndicalist activities in 1960. Anarchists helped him flee Spain and eventually reach Canada. Canadian anarchists contacted comrades in Cuba, who arranged for a visa for him to travel to the island. From Cuba, he reached Miami in 1962. There, Cuban anarchists in the city paid his travel to New York to join the SHC.

Through the publication of Frente Popular (1936-1939) and later España Libre (1939-1977), the SHC remained devoted to its antifascist cause throughout the Franco years. Lasting four decades, España Libre was the longest sustained antifascist bilingual periodical in the United States. It testifies to the grassroots and cooperative efforts of its anarchist editors. Although membership in the SHC was open to anyone advocating freedom in Spain, España Libre followed the principles of two specific unions: the Spanish anarchist union—Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT)—and the Spanish socialist union—Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT). These principles were expressed through journalism, political essays, satirical chronicles, cartoons, literature, and theater. España Libre denounced Franco’s uprising and reported on the political repression under his regime—news also reached Spain by clandestine channels—at a time when the international press showed scant interest in the execution of Franco’s political prisoners. España Libre also raised funds to provide financial and legal assistance to refugees, as well as funds for political prisoners and the underground resistance in fascist Spain. Finally, the periodical helped workers feel part of a broader antifascist and exile community, which energized their culture and politics.

United by a print culture of worker solidarity and political protest, the SHC received the support of various groups. In his role as editor of España Libre, Jesús González Malo contacted the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), IWW, the UAW and the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), gaining their support with small donations to sponsor España Libre’s printing costs. Spanish migrants who worked in the maritime industry and were members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) collaborated with the SHC, and some joined the confederation. This was the case of one of España Libre’s editors, José Castilla Morales, who organized maritime workers in Cuba before migrating to New York where he edited the IWW’s Solidaridad (1918–1930). Sailors and members of these organizations helped González Malo establish a clandestine correspondence. A postwar tactic that strengthened transnational dialogues on the development of anarcho-syndicalism within Spanish exile circles and the underground resistance in Spain. Aware that fascism in Spain was undermining the political role of workers, González Malo was determined to contest fascist, elitist, and orthodox approaches that limited workers’ access to the political forefront.

Personal experiences and interests connected local and international networks in which ethnic, radical, labor, progressive, and personal interests overlapped. The Modern Schools, which were meeting grounds where anarchists interacted with progressive thinkers and artists, were part of the confluent circuits of kinship that aided the SHC. Anarchist intellectual Rudolf Rocker arrived in the United States in 1933 from Nazi Germany; soon after his arrival, Rocker gave speeches in antifascist meetings sponsored by various organizations. In 1938, he participated in welcoming Félix Martí Ibáñez in his pro-Spanish Republic tour of the United States. Almost 20 years later, on March 25, 1952, a friend of Rocker, Roger Nash Baldwin, one of the founders of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), was invited to speak to an audience of three hundred antifascists at the Freedom House in New York. Organized by the SHC, the meeting denounced the execution of five syndicalist workers in Spain. By organizing rallies and fundraisers and protesting in the streets, SHC furthered the cause of antifascism.

Sergio Aragonés cartoon in España Libre. Courtesy of Montse Feu/Recovering the US Hispanic Literary Project.

Women members in the SHC led street protests and fundraisers in support of political dissenters and prisoners in Spain. Refugees often escaped Spain as stowaways in ships or enrolled as sailors and would desert on arrival in the USA. The SHC provided legal support to prevent deportations back to Spain, and the SHC paid for their passages to travel to visa-granting countries. The SHC secretary, Carmen Cordellat, assisted refugees with legal paperwork and funds. Women also made possible the SHC antifascist theatre that never ceased to raise funds to support refugees and prisoners while galvanizing the exile community with popular dramaturgic genres.

In most cases, the effort to help refugees was a collaboration that involved several organizations. For example, the SHC cooperated with the Spanish Refugee Aid (SRA), which helped refugees in France. Both organizations shared their membership lists, and the executive committee members attended the other organization’s meetings. Nancy Macdonald, was the leading figure of the SRA since its founding in 1953 until her retirement in 1983, held an honorary membership in SHC.

The Spanish Civil War exile print culture cannot be understood on political terms alone but rather in the transformative role that culture had—in the forms of cartoons, satirical chronicles, literature, and theater—for members in their fight against fascism. España Libre’s editors, contributors, and readers adapted in exile and created a postwar identity through a diverse body of cultural work. Creative expression was one of the most revolutionary means of fighting fascism because it enlarged members’ comprehension of their reality and the significance of resistance.

When the anarchist movement was decimated in Spain during decades of fascist terror, the greater Spanish anarchist movement did not disappear; instead, it remained operational in the transnational print and epistolary networks of exile. In addition to focusing on solidarity, España Libre safeguarded anarchist thought and practice. In her search for an affirmative political project that went beyond the pain of antifascist exile, SHC member Carmen Aldecoa researched and wrote on the broad political legacies of anarchist transnational journalism extending back to the nineteenth century. In Del sentir y pensar (Of feeling and thinking, 1957), Aldecoa sought to preserve the history of labor print culture that was being erased by Franco’s censors. Recovering labor print culture and literature, she demonstrated the impact of anarchism on the education of workers and society at large, showing that the anarchist press was a significant medium for circulation of ideas among workers in pre–civil war Spain.

When the anarchist movement was decimated in Spain during decades of fascist terror, the greater Spanish anarchist movement did not disappear; instead, it remained operational in the transnational print and epistolary networks of exile. In addition to focusing on solidarity, España Libre safeguarded anarchist thought and practice. In her search for an affirmative political project that went beyond the pain of antifascist exile, SHC member Carmen Aldecoa researched and wrote on the broad political legacies of anarchist transnational journalism extending back to the nineteenth century. In Del sentir y pensar (Of feeling and thinking, 1957), Aldecoa sought to preserve the history of labor print culture that was being erased by Franco’s censors. Recovering labor print culture and literature, she demonstrated the impact of anarchism on the education of workers and society at large, showing that the anarchist press was a significant medium for circulation of ideas among workers in pre–civil war Spain.

Another example of this effort was the work of Miguel Giménez Igualada, who wrote several books in the 1960s against the vilification suffered by the anarchist movement during the Cold War. Giménez Igualada sought to undo stereotyped perceptions of anarchism as terrorism and to reaffirm its values of cooperation, egalitarianism, and peace. Inspired by his exilic experiences in the Southwest, the novelist Ramón J. Sender, who contributed to España Libre, elaborated on the meaning of borders and freedom in Relatos fronterizos (1970), a collection of short stories that fictionalized border-crossers and their re-conceptualization of freedom as cooperation and mutual aid, key to the anarchist understanding of liberty. His protagonists represented the later twentieth-century freedom fighters, concerned with fascist subjugation still relevant today.

These later trajectories of SHC members show that the development of anarchist ideas was linked not only to legacies from the Spanish Revolution but also to their evolution in the United States. For example, Félix Martí Ibáñez transferred his anarchist utopian thinking to the magical short stories he wrote for the highly regarded medical magazine he founded, MD, providing mainstream readers with opportunities to consider everyday revolutionary possibilities. Moving toward a postmodern approach, revolution was exercised by political inclusion rather than through a violent contest of political power. Likewise, España Libre’s editorial cartoonist Sergio Aragonés transferred his tongue-in-cheek critical take on the fascist myths of power, perfection, and regenerative death to the representation of American life in Mad magazine by demythologizing totalitarian tendencies in democratic societies. Antifascist culture left a lasting impression on him, and his pantomimes continue to foreground joy and inquisitive thinking, practices exercised by the anarchist exile community that welcomed him to New York. Malleable and persistent, the anarchists of the SHC were a political and cultural backbone of antifascism in the United States.

Montse Feu, an associate professor at Sam Houston State University, is the author of Fighting Fascist Spain. Worker Protest from the Printing Press (U of Illinois P, (2020) and Correspondencia personal y política de un anarcosindicalista exiliado: Jesús González Malo (1943-1965) (Universidad de Cantabria, 2016); she has co-edited Writing Revolution: Hispanic Anarchism in the United States (U of Illinois P, 2019).

Thank you for this wonderful piece! Would you happen to have a pdf of Aldecoa’s Del sentir y pensar? Thank you again.

Thank you for your question. You can get hold of the book via interlibrary loan at your local library.

https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007973644