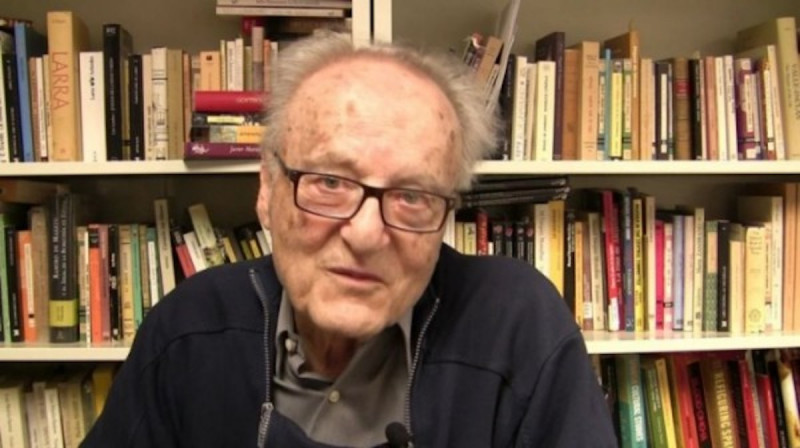

Gabriel Jackson (1921-2019)

“Se nos ha ido Gabriel Jackson”—“Gabriel Jackson Has Left Us.” The 2010 headline in La Vanguardia, Catalonia’s newspaper of record, almost looked like an obituary. It wasn’t: the author, Francesc de Carreras, lamented that Jackson, one of the world’s most prominent historians of twentieth-century Spain, had decided to move back to the United States. After spending 26 years in Barcelona, Jackson wanted to be closer to his family in Oregon. “It’s impossible,” the article said, “to imagine someone more down-to-earth—someone kinder, more educated, discreet, tolerant, austere, always ready to lend a hand to the weak, incapable of flattering those in power.”

It was in Oregon that Gabe Jackson, who served for many years on ALBA’s Board and Honorary Board of Governors, passed away this November 3, at the age of 98. His last published book, which came out in Spanish in 2008 and in English two years later, was a biography of Juan Negrín, the much-maligned Prime Minister of the Spanish Republic during the last years of the Civil War. Jackson strongly defended Negrín’s controversial decision to not surrender to the rebels led by Francisco Franco. “Negrín’s policy of resistance and constant diplomatic effort was the right one,” Jackson said in an interview with The Volunteer in 2010, adding: “I am also convinced that if England and France had supported the Republic and stood up to Hitler, history would have taken a different course. … If the democratic countries had aided the Republic so that Franco would not have had the complete victory that he did, we need not have had a Second World War, or it would not have occurred in the terribly disastrous fashion that it did.”

Jackson was born into a Jewish family in Mount Vernon, New York, on March 10, 1921. At an early age he was drawn to music, which would become a lifelong passion. A semiprofessional flautist, he also wrote a novelized biography of Mozart. His interest in Spain was sparked by the Civil War, which broke out when Jackson was 15 years old. “I was an avid newspaper reader and quite politically conscious already,” he said in the same interview. “I clearly remember the heated dinner table discussions on Spain between my father, who was a Socialist, and my Communist older brother.”

In the summer of 1942, after graduating from Harvard College, Jackson spent two months in Mexico on a fellowship. “Now of course Mexico City in 1942 was full of Spanish Republican exiles,” he recalled. “It was meeting and speaking with them that further opened my eyes to the history of Spain and Latin America.” Together with two Princeton students, Jackson stayed at the home of an exiled Republican physician. In the apartment upstairs lived the widow of President Manuel Azaña, who had died in France in 1939. “She often came down to have coffee and cigarettes; we played dominos after lunch.”

After spending World War II as a cartographer in the Pacific, Jackson earned a Master’s degree at Stanford with a thesis on the educational program of the Second Spanish Republic. In 1950, he and his wife began their doctoral studies at the University of Toulouse in Southern France, resulting in a dissertation on the work of Joaquín Costa. Jackson also met many of the thousands of Spanish Republican refugees living in that city.

The fall of 1952 found the Jacksons reluctantly back in the States, where Jackson initially had trouble finding steady academic work. His refusal to supply information about his classmates to the FBI had landed him on Roy Cohn’s list. After three years at Goddard College, five at Wellesley—where he became close friends with the exiled Spanish poet Jorge Guillén—and three at Knox College in Illinois, Jackson finally landed a tenure-track job at the University of California at San Diego, in 1965. Princeton had just published his The Spanish Republic and the Civil War.

Jackson’s book helped put twentieth-century Spanish history back on the academic map, earning him the 1966 Herbert Baxter Adams Prize of the American Historical Association. Its appearance did not go unnoticed in Spain, either. “I’ve been told it made a considerable scandal among regime circles—especially the appendix, which gave estimated numbers of victims of Nationalist repression,” he said. “Together with Herbert Southworth’s La cruzada de Francisco Franco and Hugh Thomas’s The Spanish Civil War which had come out in 1961, it motivated the Spanish government to initiate a whole new line of research to defend the Francoist record in the war.” Among his later books are The Spanish Civil War (1967), The Making of Medieval Spain (1972), and Civilization & Barbarity in 20th Century Europe (1999), and Juan Negrin: Physiologist, Socialist, and Spanish Republican War Leader (2010).

As an historian, Jackson believed in intellectual rigor but rejected narrow notions of objectivity. In a subject like the Spanish Civil War, he said, “it’s impossible—and in fact not desirable—to try to conceal one’s emotions or political views. My idea of objectivity is that you don’t hide your emotions or pretend not to have them, but that you are honest and open about them from the outset. As an historian you have not only have to account for your sources, but also explain why you have the sympathies you have. The rest is up to the reader.”

Jackson began befriending veterans of the Lincoln Brigade in the 1940s. “They were a feisty bunch,” he said of the vets. “Although I never had an actual fight with Bill Susman, I was very much of aware of his disappointment in a novel that I wrote, in which the hero is a Spanish Anarchist, an illegal immigrant from Mexico to the United States. My evident sympathy for a certain kind of truly idealistic Anarchist was not something that Susman appreciated.” Jackson was among the first to be invited to give the annual lecture created in Bill Susman’s honor.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College. This obituary draws on a 2010 interview with Jackson published in The Volunteer.