William Loren Katz (1927-2019)

With the passing of William Loren Katz, the world has lost a great historian and educator. Katz helped reshape the way American history is taught, publishing over 40 books on African American, Native American, and progressive history and editing two major series totaling over 200 books on anti-slavery resistance and African American thought. His lifetime commitment to re-narrating an inclusive and truthful American history and combatting fascism and racism affirms the power of populist historiography and of publishing. His work influenced generations of young scholars and artists and an array of major figures including Alice Walker, Henry Louis Gates, LL Cool J, Danny Glover, and Herb Boyd. He was in conversation with key thinkers such as Langston Hughes, John Hope Franklin, and Robin D.G. Kelley. He narrated stories of solidarity between African American and Indigenous peoples, anti-fascist alliances, slave rebellions and anti-slavery movements, and heroic black women, when voicing these tales was dangerous and even unpatriotic.

His ethical commitment to historical writing begins from a deep family legacy of addressing the silences and correcting the power imbalances in the story of America. Katz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1927. His mother was an Olympic diver, who died when he was young. His father was an amateur historian, Jazz organizer, and labor activist, who was a founding member of the Committee for the Negro in the Arts in the 1940s. His younger brother Jonathan Ned Katz would become a significant historian shaping LGBTQ historiography. From a young age, Katz recognized the importance of solidarity from the perspective of a progressive Jewish background. He was in the first graduating class at the progressive Elizabeth Irwin High School in Greenwich Village. He was part of the progressive political and artistic scene that circulated through the school and the neighborhood and met figures like Paul Robeson, Harry Belafonte, Woody Guthrie, and Pete Seeger.

Katz was in the Navy, serving on a ship in the Pacific theater in World War II. He was appalled by how the Captain enforced segregation of black troops on board, and how some troops delighted in talking about lynchings back home and calling him a “dirty Jew.” Katz’s family was harassed by the FBI during the Communist scares of the 1950s. Katz recalled two agents coming to his father’s house, seeing African American history books and asking “Mr. Katz if you say you are not a Communist why do you have so many books about Negroes?” Katz recalled trying to attend Paul Robeson’s benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress in 1949— dubbed the Peekskill race riots—where Blacks and Jews were attacked as communists while police stood by and watched. He attended a vigil in Union Square for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg June 19, 1953, the night they were executed for espionage. For Katz, state-sponsored terror linking communism to Black life and Jewish existence pointed to the fascist global political climate shaping how American stories were told.

From the 1960s through the 1980s his work made him a major figure; in some ways his success in helping reshape how history is written and taught means that we forget the vision, endurance, and courage his work—along with that of many others—required. And he did this without institutional backing or ever holding a permanent academic position.

From the 1960s through the 1980s his work made him a major figure; in some ways his success in helping reshape how history is written and taught means that we forget the vision, endurance, and courage his work—along with that of many others—required. And he did this without institutional backing or ever holding a permanent academic position.

His book Eyewitness published in 1967 was, amazingly, inspired by his students at Woodlands High School. He describes his frustration and anger at the fact that American history was taught from a white supremacist perspective erasing the humanity of African and indigenous peoples. This elision inspired him to spend his life correcting this mistake. His theoretical brilliance lies in that his books are accessible to children of all ages; they can be read out loud to school children or taught in universities.

In the late 1960s, The New York Times hired Katz to edit two groundbreaking series for Arno Press: “The American Negro: His History and Literature” and “Anti-Slavery Crusade in America.” It turns out there were over 200 books published under Katz’s leadership that brought key books on African American history, narratives, and resistance to the public eye; some were contemporary scholarly works, others were key unseen or out of print texts from the 19th century onwards by African American authors.

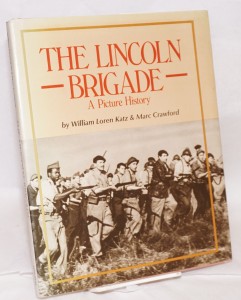

Much of his work tried to elevate stories of bravery and humanity that have been neglected by sanctioned accountings of American life. The Black West, originally published in 1973, tells the history of African American cowboys and why American history portrays the old west as white. In The Lincoln Brigade written with Marc Crawford, Katz examines the legacy of Americans who volunteered to fight fascism in Spain in the 1930s.

His book Black Indians, originally published in 1986 and recently reissued, was groundbreaking in showing links between African Americans and Native Americans not normally recognized; he continues to receive recognition for this work from Native American groups around the country. This text shows ways that the American story has criminalized black and indigenous peoples and has sought to keep them separate, despite overwhelming evidence of their alliances, to maintain a narrative of white supremacist dominance. In its introduction (p. 8) he writes of the daunting task of re-narrating history, “I have been humbled by the awesome task of rejecting bias. … I have never sought bland neutrality and have consoled myself that unbiased history has yet to be written.”

His struggle to change the national narrative also entailed revealing how extremisms are normalized. InThe Invisible Empire: The Ku Klux Klan Impact on History Katz examines how racial violence was normalized and justified. Indeed, even in attempting to publish this work in the 1980s he faced opposition from publishers who felt he did not properly contextualize KKK violence.

The elegance of his research is that he studied what was in plain sight, reexamining the public record and amplifying the voices of people ignored as peripheral to ideas of historical progress. Katz’s brilliance was in the minimalist simplicity of his projects’ research design and his enduring belief that the way we tell stories about the past affects how that particularly young people imagine possibilities for their future. He pioneered visual and multi-media storytelling, using photographs and images as evidence and juxtaposing them with first-hand accounts and archival materials.

These books were revolutionary. Indeed, there has been a recent resurgence of interest in this work with the rise of writers and filmmakers portrayals of black heroes. Young artists and scholars would continue to write to Katz to say that his work was what originally opened their eyes to alternative narratives and taught them to seek their own ways of telling stories. Katz’s work was crucial for so many to discover that freedom was not given over by the powerful, but rather was fought for. He insisted on the agency of oppressed peoples and on the importance of both large-scale active resistance and on mundane acts that make life livable.

Jesse Weaver Shipley is an artist, ethnographer, and teacher whose work focuses on the aesthetics of power. He is a Professor of African and African American Studies and Oratory at Dartmouth College.

La libertat como bien sabemos los pueblos que a traves de su historia en algun momento no te la regalan, SE CONQUISTA Y SI ES NECESARIO CON UNA REVOLUCIÓN.

Un abrazo compañeros.

Josep

Faltaba esto. Disculpen.

……. historia, hemos sido oprimidos en algun momento no te la regalan. SE CONQUISTA……..