The Antifascist Tower of Babel: Language Barriers in Civil-War Spain

The International Brigades were a hybrid bunch: multi-ethnic, multi-national—and multi-lingual: not everybody spoke everybody’s language. This posed serious organizational challenges for the Republican war effort.

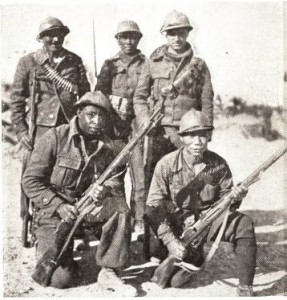

Irish volunteers in Spain: Eddie Flaherty, Company Commander, extreme left, standing. From the Book of the XV Brigade.

Many of the 40,000 foreign volunteers who traveled to Spain to fight fascism as soldiers, advisors, or medical workers were migrants and political exiles. Between 32,000 and 35,000 joined the International Brigades (IBs) created by the Communist international. The hybrid culture they embodied was the antithesis of fascism. In fact, their experience in Spain helped shape a new antifascist transnational identity. Yet the multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, and multi-lingual nature of the Brigades also posed serious organizational challenges for the Republican war effort.

In addition to around 30 European languages, the linguistic symphony of the IBs included more exotic tongues such as Turkish, Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese. Both in the internal reports of the IBs and in the memoirs of the volunteers we find recurrent references to the Tower of Babel, the biblical story in which God punishes humanity’s hubris by cursing it with linguistic division.

On the one hand, the military leadership highlighted that the Brigades’ linguistic melting pot represented the new world that antifascism was trying to build beyond ethnic or linguistic barriers. On the other, they recognized that it presented enormous problems in practical terms, turning into a cacophony that provoked high levels of confusion and misunderstanding.

To be sure, most of the main leaders of the International Brigades were polyglots, speaking to each other in French, Spanish, and Russian. In fact, Russian became a sign of distinction among the IB elites, as many had gained military experience in the Soviet Union. Yet given that the largest contingent of volunteers came from France—whether they were French or had lived there in exile—the first official language of the IBs was French. The problem was that many of the volunteers who arrived in Spain did not understand French.

The IBs rushed to organize in mid-October 1936 and had their baptism of fire only two weeks later, in early November, in an attempt to prevent the fascist occupation of Madrid. While the participation of the IBs was key in defending the capital of the Republic, it also showed the difficulties of managing multi-lingual units. Sometimes orders had to be translated orally into up to three languages, inevitably causing misunderstandings in this chain of translations.

Driven by a utopian and idealistic vision, André Marty wanted to maintain the multilingualism of the battalions.

After November 1936, some high commanders of the IBs pointed out that it was necessary to create linguistically homogeneous battalions to reinforce the military efficiency of the units on the battlefield. Yet the IB’s top leader, André Marty, was against this measure. Driven by a utopian and idealistic vision, he defended that it was necessary to maintain the multilingualism of the battalions in order not to break the international unity of the IBs.

This policy was maintained from November 1936 until March 1937. But the language problems generated on the battlefield in the Battle of Jarama convinced the high commanders of the International Brigades that it was necessary to establish a new policy. In April 1937 the high command of the IBs began to reorganize the soldiers, moving battalions between brigades, trying to gather groups based on the prevailing languages. Thus the 11th Brigade (German), the 12th Brigade (Italian), and the 14th Brigade (French) were established, at the same time that a new multilingual Brigade was created composed of volunteers from Eastern Europe, who spoke many languages given the multiethnic nature of the ancient Austro-Hungarian empire.

Still, the high command of the IBs was soon faced with a new linguistic challenge. Starting in February 1937 the IB units were accepting Spanish soldiers due to the lack of international volunteers to supply the battalions. By May, some battalions had more Spanish soldiers than foreigners. The Spaniards did not know the official languages of each of the military units.

Faced with this situation, the high command of the IBs decided to “Hispanicize” the battalions. The objective was to move from the existing linguistic policy towards bilingualism. Thus, the new brigades had to combine two official languages: Spanish-German (11th Brigade), Spanish-Italian (12th Brigade), Spanish-Slavic languages (13th Brigade), Spanish-French (14th Brigade) and Spanish-English (15th Brigade).

This new policy helped to improve the military effectiveness of the IBs, although communication difficulties continued throughout the rest of the war. To this end, the IBs were assisted by translators and interpreters who tried to build bridges of communication. Spanish courses were also offered to volunteers, although they were only compulsory in the 13th Brigade, where the predominant multilingualism was conducive to language learning.

In addition to Spanish, Yiddish became an important language of communication among volunteers of different nationalities, many of whom were Yiddish speakers who had fled the fascist and authoritarian regimes of Eastern and Central Europe, along with others from Western countries, especially the USA. In fact, for many of these volunteers their experience in Spain meant recovering the lost Yiddish of their childhood.

The multilingualism of the IBs generated enormous communication difficulties in practical terms, but also offered an opportunity to build and strengthen a new slang and antifascist culture. Many brigadistas ended up speaking a hybrid language that contained words and grammatical structures of different languages. Numerous Spanish loanwords made it into their everyday vocabulary. Two of the most common words used by the Spanish brigadistas were “Salud” and “Camarada,” which were immediately incorporated into the international antifascist vocabulary.

During the Second World War, many international volunteers, together with their Spanish comrades, brought this new anti-fascist language and identity to the concentration camps and resistance movements in their respective countries. On the lips of these “Spanci”—a nickname for former IBs volunteers derived from various Eastern European languages—the new hybrid language forged on Spanish soil resounded across the mountains, forests, and deserts of occupied Europe and North Africa.

Jorge Marco teaches Spanish Politics, History & Society at the University of Bath (UK). This article draws on “‘Mucho malo for fascisti’: Languages and Transnational Soldiers in the Spanish Civil War,” co-authored with Maria Thomas and published in War & Society (vol. 38, no. 2). English version by Sebastiaan Faber.

[…] The original version of this article was published in English at The Volunteer. […]

Thanks for the article – fascinating. And especially for the evocative and heroic photographs. ¡viva el internacionalismo!