Dreaming Wide Awake in the Archives

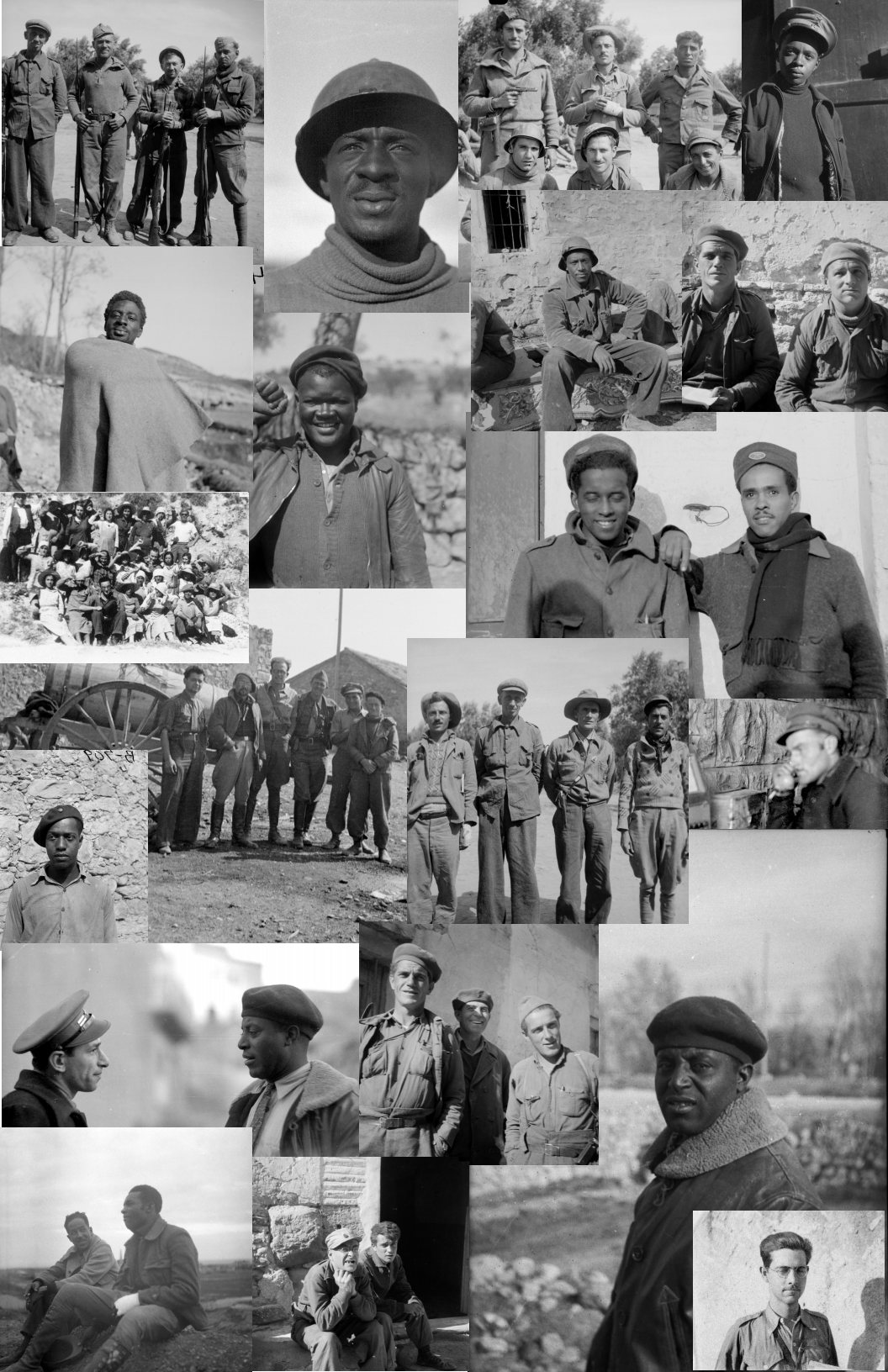

The ALBA collection at NYU’s Tamiment Library is an extraordinary trove of documents, images, and artifacts chronicling the lives of the almost 3,000 American men and women who joined the Spanish Civil War. It collection represents about ten percent of these volunteers—a respectable sampling. But is it representative?

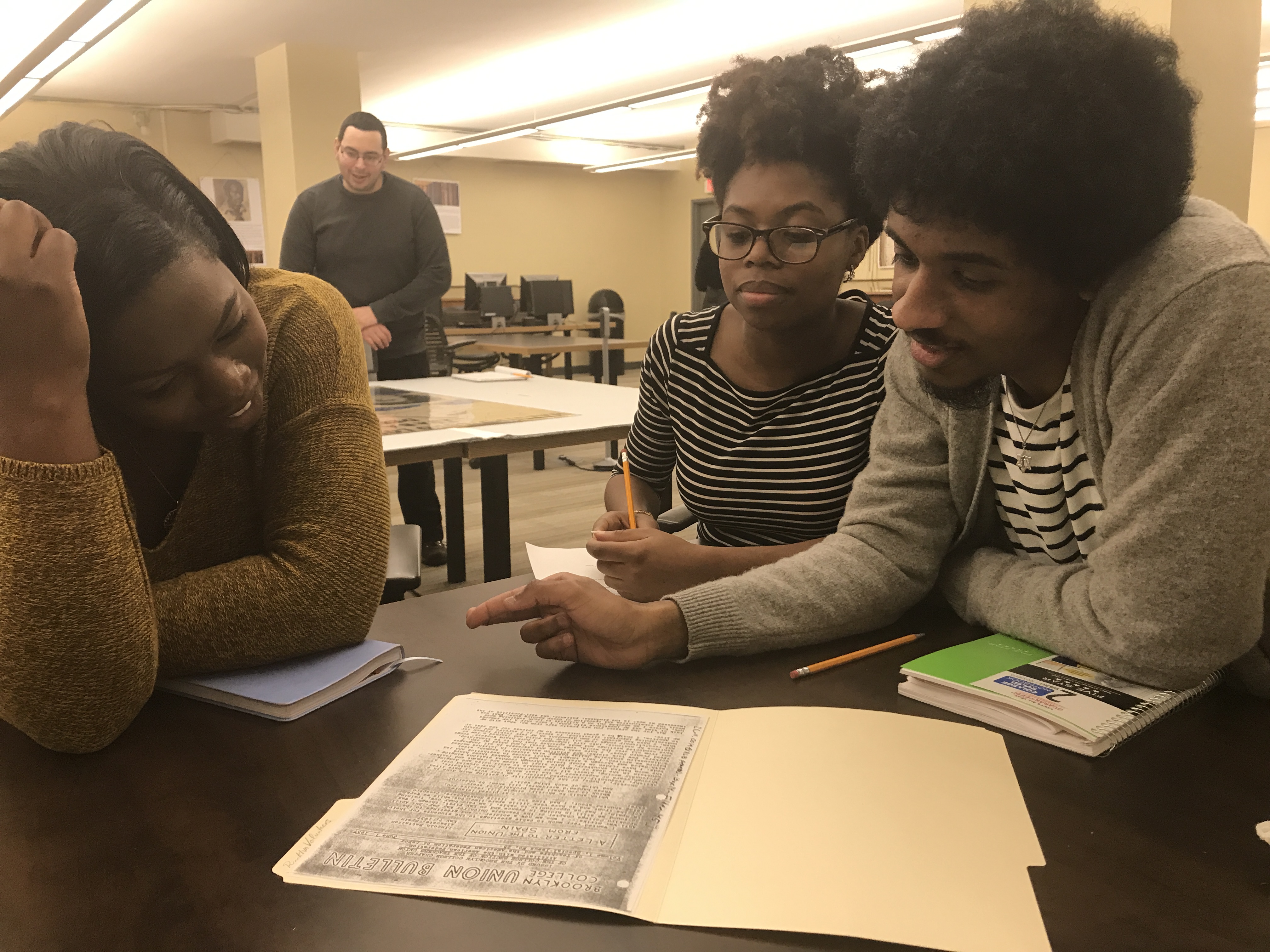

Hunter College students research the ALBA Collection at the Tamiment Library (NYU), April 2018. Photo María Hernández Ojeda.

Making private memoranda of our thoughts from time to time, so far from necessarily proving a help to the accuracy of the memory may, if especial care be not taken to guard against the danger, tend even to mislead the memory; because it may occasion our forgetting more completely whatever we do not enter in the book…Hence, there is the danger of our remembrance becoming not like a book partially defaced and torn, in which we perceive what deficiencies are to be accounted for, but more like a transcript from a decayed MS, which the ancient copyists, by trade used to make: writing straight on all they could make out and omitting the rest without any marks of omission, for fear of spoiling the look of their copy.

—Richard Whately (1866)

“The Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives—ALBA—housed at NYU’s Tamiment Library, is the most important collection of documents, images and artifacts in the world chronicling the lives of the almost 3,000 American men and women who, between 1936 and 1939, volunteered to join the fight against fascism in Spain.” Over the last twenty years, I’ve probably repeated that sentence dozens of times, in articles, blog posts, talks, grant applications, classrooms, workshops and even in a documentary short.

This extraordinary collection of primary sources about an extraordinary group of people has occupied a prominent place in my research, teaching and everyday life since I arrived at NYU. The archives came to Washington Square from Brandeis University in 2000. A handful of veterans had deposited their personal files there in the late 1970s, as they approached retirement age and found themselves with the time and the inclination to fret about the final resting place of their long and precarious paper trail, to worry about the fate of their legacy. They had good reason to be concerned.

It was in December of 1936—a full five years before Pearl Harbor—that the first contingent of American anti-fascist fighters boarded a ship in New York’s Hudson docks, bound for Spain. They were breaking US law by volunteering to help the Spanish Second Republic defend itself from the military coup that had been spearheaded by a group of right-wing generals, backed by Hitler and Mussolini. In the US at the time, non-intervention and appeasement underwrote the law of the land; passports were being stamped: “Not valid for travel to Spain.” The Communist Party took charge of the recruitment and travel logistics of the volunteers, and the Soviet Union was one of the only countries that intervened in the Spanish Civil War on behalf of the Republic. Some 40,000 volunteers from more than 50 countries would end up serving in the International Brigades before the Spanish war ended in the Spring of 1939, with the defeat of the Republic and a pro-Axis dictatorship firmly in place.

The fact that the volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade had bravely taken up the fight against Franco, Hitler and Mussolini as early as 1936 would bolster their image for many people in the years leading up to, and immediately following, US involvement in WWII. Robert Jordan, the rugged and sympathetic hero of Hemingway’s 1940 novel, From Whom the Bell Tolls, was a fictionalized version of an American anti-fascist volunteer. As was Bogart’s gruff and beloved character in the legendary Casablanca (1942); in a key scene of the film, Renault reminds the “I-stick-my-neck-out-for-nobody” Rick Blaine of his commitment to antifascism by recalling his altruistic service on the Loyalist side in Spain.

The fact that the volunteers had been recruited and organized by the communist party, and had fought in Spain alongside forces supported by the USSR, would tarnish their image for many people, especially as the anti-fascist imperatives of the Hot War gave way to the anti-communist fervor of the Cold War. To further complicate evolving popular perceptions of the Lincolns: after the defeat of the Axis, a fox-like Franco forswore his friendship with Adolf and Benito, retooled himself as an upstanding and indispensable ally in the struggle against communism, and—voila—soon welcomed Eisenhower—and American military bases—to Spain. Just a few more decades of Cold War revisionism would have to pass before another American president, Ronald Reagan, could blithely declare—as he defended his covert support of anti-sandinista “contras” in Nicaragua—that the Lincolns had actually fought on the wrong side in the Spanish Civil War.

“Setting the record straight” is often the driving force behind the creation of archives. Being suspected of having been on the wrong side of history would have been a major impetus for the constitution of ALBA in the late 1970s and early 80s. That’s when that original handful of veterans decided to bring together their personal papers into a collective archive, which would document their early lives, their reasons for going to Spain, their experiences while there, their post-war activities, and, in many cases, the harassment, persecution and misunderstanding they had to endure after returning from Spain. Many of the volunteers represented in the archive were remarkably self-conscious chroniclers of their own lives and times; almost as if they were aware of controversies to come, they often kept detailed diaries, wrote thousands of letters, and collected, while in Spain, all manner of printed matter, photographs and ephemera, including not only Republican propaganda posters and handbills, but also things like cigarette packs, bar napkins, and even, in one case, the business card and photograph of a certain Madame Albita from Barcelona’s red light district. The immense and diverse collection has expanded exponentially over the years; its core is now made up of the personal archives of almost 300 veterans—roughly 10% of the total number of volunteers—and is supplemented by a still growing amount of related materials: books and pamphlets, photographs, postcards, FBI files, research notes for publications and films about the Lincolns, as well as the administrative records of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, founded in 1937, when the first American wounded began returning from Spain.

Students who immerse themselves in the ALBA collection invariably come away with valuable lessons that have quietly been written out of the dominant, shared narratives about our past:

How there were many people in the US who long before 1941 clearly understood the menace that fascism posed for the entire world, and were willing to do something drastic about it; or how the anti-fascist credentials of the United States and its “Greatest Generation” need to be put into perspective; or how a working class identity—which cuts across race, creed, ethnicity, gender and nationality—was a powerful motivating force for many in the United States just 80 years ago. The ALBA collections, in this regard, constitute an invaluable counter-archive, made up precisely of what often gets left out of the unspoiled copy of the book of US self-righteousness and exceptionalism.

At the same time, however, this archive—like all archives—poses significant challenges and risks. The apparent exhaustiveness of these compelling collections, together with our parching thirst, in this age of fake news, for the Real, can lead us to let our guard down, to take the part for the whole, to forget that every set of documents, no matter how vast, has its own history, its own agenda, its own unmarked omissions and silences. The 10% of volunteers most fully represented in the collection is a respectable—but not representative—sampling. Probably twice as many volunteers died in Spain—and except for the tributes, they were often rendered by those who returned, we can learn little in Tamiment about them and their thoughts about the war. Another 10% of the volunteers had Spanish last names, but, for a complex set of reasons yet to be sorted out, not a single collection of theirs survives in the ALBA collections. Hundreds of volunteers returned from Spain and chose to sideline or in some cases even hide their experience in Spain; most of their stories are, for now, lost to us. And those who were disillusioned or bitter about their time in Spain were, it stands to reason, disinclined to contribute their personal archives to the ALBA collections.

Students who hope to find in the archives the rock-solid ground of “what really happened” are almost always disappointed. As well they should be. And not only because there are “missing” documents, missing voices. “He told his mother he was going to Spain for one reason, and he told his girlfriend he was going for a different reason.” “In 1937 she says that she went to Spain for one reason, and in 1947, she says she went for another.” The documents, more often than not, offer interpretations and interventions, that themselves need to be interpreted, intervened. Not exhaustive, but exhausting; there’s no rest for the weary in the archive. More than access to a self-present and unmediated past, the archive allows us to glimpse a repertoire of some of the unrealized or aborted futures that haunted someone else’s present. And more than providing a repository of firm answers about the past, an archive like the ALBA collection, when engaged critically, while wide awake, allows us to dream up new questions about our own futures.

James D. Fernández is Professor of Spanish at NYU and a longtime contributor to The Volunteer. This essay originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of ESFERAS, the undergraduate student journal of NYU’s Department of Spanish and Portuguese.