Teaching Art and Politics of the Spanish Civil War

Time, by José María Sert, ceiling of Main Lobby in 30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York. Photo Khjara (CC BY-SA 3.0)

High school history teachers who struggle to find room in their curriculum to teach the Spanish Civil War. One way to create space is to introduce the topic as part of broader thematic units—for example, on twentieth-century art and politics. Why did some artists of the avant-garde end up on Franco’s side, while others sided with the Republic?

The Spanish Civil War is of great personal interest to me. Yet even though my course on European history gives me some flexibility, like many teachers I often find myself in a struggle against the clock to fit in the topic, usually in the spring. In the past, I have focused on the causes and effects of the war in a unit that included an analysis of Picasso’s painting Guernica. Still, I am always left wishing I could do more. This year, I decided to dedicate more time to the topic through a thematic approach to art and politics that includes examples from the 1930s.

My inspiration was the result of two visits I made to two cities about a month apart. The first was the Joan Miró exhibit on display at the Grand Palais in Paris. The second was to 30 Rockefeller Center in New York. This building contains murals by a number of artists; but the most impressive by far are those painted by Josep Maria Sert on the ceiling above the building’s main entrance. His mural Time (see illustration) conveys a stunning sense of movement and energy. Why, I wondered, had I never heard of Sert? The gap in my knowledge was all the more enigmatic because I had long been familiar with the work of his contemporaries, including Joan Miró. The answer, it turned out, lay in the Spanish Civil War.

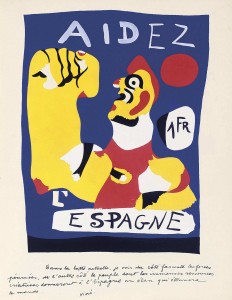

Both Miró and Sert were Catalans by birth. Born about twenty years apart, in 1874 and 1893 respectively, both eventually made their way to Paris in the early decades of the twentieth century and became fixtures of the avant-garde. Sert painted sets for the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghilev. Miró pioneered the Surrealist movement. Both received important commissions. In 1932, Sert was hired by the Rockefeller family to paint a mural for their building after they famously dismissed Diego Rivera for painting one they deemed too overtly political. Five years later, Miró was asked by those organizing the Republic’s exhibition at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair to create a design promoting the Spanish Pavilion. At the current exhibit in Paris, one part is dedicated to Miró’s work during the 1930s, including the ’37 Fair. (Curiously, the Spanish Pavilion was designed by Sert’s nephew, the architect Josep Lluís Sert.)

Along with Picasso and the American sculptor Alexander Calder, Miró was one of a number of artists whose creative contributions during the years of the Civil War were more than art—they were expressions of solidarity with a government under siege. Sert, who was only just completing his series of murals for the League of Nations headquarters in Geneva when the war in Spain broke out, threw his support to the franquistas, lending both his talents and his prestige to the fascist side. While Franco emerged victorious inside Spain, the Axis was defeated six years later; fascism in Europe and elsewhere was discredited and unfashionable. So, it would seem, was Sert.

The cases of Sert and Miró bring up several questions that I’m curious to explore with my European history students. To what degree is art political? Should it be? How do an artist’s political views color our understanding of, and appreciation for, their work? After all, Adolf Hitler was a watercolorist in Vienna before World War I. On the other hand, the painter Edgar Degas was an anti-Dreyfusard with publicly known anti-Semitic views. Should we reject his work, too?

Because the Spanish Civil War overtly enlisted painters, writers, poets, and photographers as propagandists, it is an excellent lens through which to view these questions. A unit that includes exposure to a larger body of work from both Miró and Sert, and an examination of their lives and careers as a whole both before and after the war, can place these questions in context and spark an informed discussion. Should artists take sides in a political conflict? Do they in fact have a choice? A field trip to 30 Rockefeller Center and to MoMA to see Miró’s painting The Hunter (1923-24) could enhance the discussion further. Art, after all, can connect students to history in a different, more accessible way. And many of the questions sparked by the Spanish Civil War are just as relevant today as they were eighty years ago.

David Hanna teaches history at Stuyvesant High School in New York. He is a recipient of the New York Times Teachers Make a Difference Award.

Dear Mr. Hanna –

I enjoyed your discussion of Spanish artists and the war. But you left out one important artist. Luis Quintanilla, who painted the murals for the Spanish Pavillion of the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. http://www.lqart.org/muralfold/fresco.html#Peace

He also did a series of 140 drawings of the war which were shown in 1938 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art with a catalog by Hemingway. http://www.lqart.org/civwarfold/wardraws.html

Pretty much forgotten today, though he is enjoying a revival in Spain, he was once considered an important Spanish artist. “The artist of the Spanish people,” “a great man and great artist,” as Hemingway put it.

I admit I might be prejudiced since I am the artist’s son. But I just thought I would point point out his existence to you, and accompany it with some documentation which supports my claim.

Best wishes, Paul Quintanilla

Mr. Quintanilla,

Thank you for reaching out. I wasn’t aware of you father’s work. Thank you for sharing this with me. I would like to have you speak to my students about the panels for the ’39 Fair. Please let me know if this would interest you.

Regards,

D. Hanna