Faces of ALBA: Dean Burrier Sanchis

Dean Burrier Sanchis is a Spanish teacher and soccer coach in Elk Grove, Illinois. He also has a deep personal connection to the Spanish Civil War. Dean has spent several years uncovering and documenting the life story of his grandfather and Lincoln veteran Vicente Sanchis Amades. His blog can be found here.

Your grandfather Vicente Sanchis Amades was born in Spain and immigrated to the US in 1923 at the age of 16. Do you know why he decided to return to fight in the Lincoln Brigade in 1938?

He believed in democracy and fighting for it at all costs. He had served in the US Army and Navy and had even been part of the US intervention in Nicaragua overseeing its elections. Despite having suffered injuries in combat there, he was not afraid to put his life on the line again for democracy. I recovered a letter from the State Department written by his friends to President Franklin Roosevelt when my grandfather was a POW at San Pedro de la Cardeña that stated that he was stirred to “go back and fight for democracy in his own country.” Another letter attested to his anti-fascist motives: “He started off to fight Fascists. He believed…this was not merely a war to save his homeland, but a war to save the world from Fascism and Anarchy.” Sources aside, it is clear to me that Vicente had become very integrated into the values of American society and believed deeply in the need to protect liberty around the world. I also think that being an illegal alien and recently unemployed from the Great Depression forced him to make this difficult decision.

We only know about your grandfather through your research. How did you get interested in learning more about your family and how did you track down the clues to recreate his story?

It was fate. I was raised to believe my mother’s stepfather was my grandfather. In their defense, I think it was the easy thing to do at the time and my grandmother wanted to move on with her life and new husband. I learned the truth from my mother when I was 16 after I studied abroad in Spain and fell in love with a country that I did not believe I was at all connected to. I could not help but dedicate myself to researching and discovering a man and family roots that I never knew existed. I was fascinated with the thought that my love for Spain really had a deeper explanation inside my DNA. For better or worse, it became an obsession and, in many ways, an impossible quest. I set off with a handful of mostly inconsequential memories from my mother’s childhood, a social security death certificate and the recollection that he was from Valencia. It was a long journey but in less than seven years I was able to obtain his Spanish birth certificate, become a citizen of Spain through the law of historical memory, reconstruct a very complete biography of his life, and even recover my grandfather’s remains that were held by a niece from a subsequent marriage. Having his existence hidden from me actually motivated me to pursue historical memory and recovery.

Are there any updates to your story since your last blog entry?

Too many, and there is precious little time to document them, given the demands of my career as a teacher and soccer coach, and now being a husband and father. For example, I had not shared the letters that I mentioned above until now. I also recently uncovered a WWII-era news article in which my grandfather is quoted about his experiences fighting Italian fascists in the Spanish Civil War. There is a great deal of material still left for me to pursue and share. However, these days my focus has turned toward learning about the many other Spanish-American Volunteers who left US shores for Spain. I was inspired by James Fernández to unite my story with a greater community of Spanish immigrant descendants, try to research further, and understand this exceptional group of “invisible immigrants.” In this project, titled “Reterrar,” I am creating biographical chronologies for Spanish-American volunteers—not unlike the work of another mentor, Chris Brooks, who has been a tremendous aide to me in all of my research—and trying to get a greater understanding of the motivations, contributions, and historical legacy of Spanish-American volunteers.

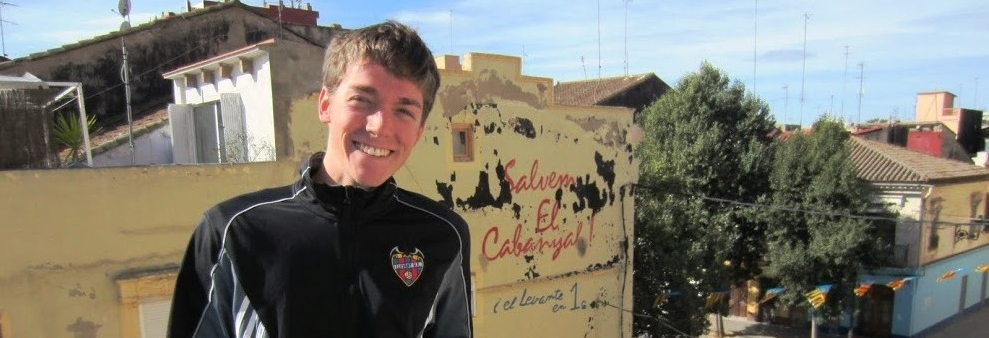

Many of us are soccer fans of particular teams (Go Clapton CFC!), but your support of Levante U.D. has a unique story. Can you tell us about it?

When I discovered that my grandfather was not just from Valencia, but from the fisherman’s neighborhood of Cabanyal, I wanted to grow closer to the emblematic beach-side community. Levante was founded mere blocks from where my grandfather once lived. Rooting for Levante started as a way to embody my love for my roots and feel connected to this place so essential to my family’s history, particularly on the side of my great-grandmother. I was also at a point in my research where I could not seem to break through. I had been trying for years to obtain a birth certificate through the Spanish consulate, but nothing could be located. Ironically, I had mostly given up when I penned a blog about how Levante was really the ultimate gift and the end point for my journey. Luckily, two long-standing granotas (as Levante fans are called) Joan Bosch and Rosa María Alcaina read the blog and reached out to me. They had been creating a genealogical database for Cabanyal and gave me census data that pointed to a birthplace other than Cabanyal. The couple grew from complete strangers to being like parents to me. Not only did they aid me in obtaining a seemingly endless amount of information about my family history, but they became trusted advisors and an indispensable support system. I called them my padrinos, or godparents, because the connection felt almost spiritual. They eventually did become my godparents when, in 2013, I was baptized in in Estivella, Spain in the same baptismal font where my grandfather was some 100 plus years before. Levante will forever be a family to me and the embodiment of my Spanish roots. Levante also has the unique legacy of being the winner of the only “Copa de la España Libre,” in the Free Spain of the Spanish Republic in 1937, champions of an as-yet unrecognized edition of the national cup, that today we know as the Copa del Rey.

You attended an ALBA teaching institute. Do you teach the Spanish Civil War or your personal story in the classroom?

Yes, I have had my students read the POW letter that my grandfather penned and that Peter Carroll helped me transcribe. I have a great deal of freedom in my curriculum planning and this has fostered opportunities to experiment with engaging new units for my students. I have had AP Spanish students study the international dimension of the war under the AP theme of “Public and Personal Identities.” I have also made connections to the refugee crisis stemming from the Spanish Civil War to current events under the “World Challenges” theme. I have made a point to include Mexico’s reception of Spanish refugees in units on Immigration. As I teach Spanish to Spanish speakers in a predominantly Mexican-American community, learning of Mexico’s rich tradition of welcoming immigrants allows for an interesting backdrop for comparisons with US current immigration policies. In the near future, I want to incorporate the study of African-American volunteers during Black History Month. I hope that when the College Board retools its national curriculum for AP Spanish Literature, more consideration will be given to including works from the Spanish Civil War period. There are virtually no opportunities to incorporate the war into the current curriculum of this course (other than through biographical information on Lorca, Unamuno or Machado, that don’t directly connect to the works selected by AP).

Aaron Retish teaches at Wayne State University.