A Chance Find at the Archive: The Life of Vicente García Riestra

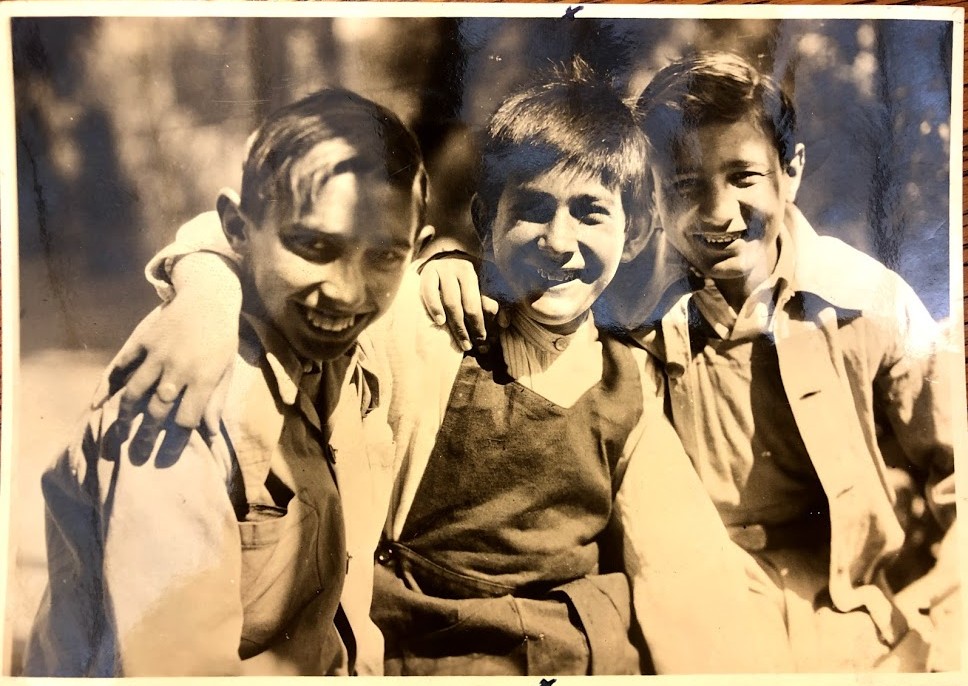

A 13-year-old García Riestra with two friends at the colonia of Torrent-Bo. American Friends of Spanish Democracy records. Manuscripts and Archives Division. The New York Public Library. Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

An old snapshot of three smiling teenagers leads a researcher to one of the Spanish survivors of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

While browsing through the archival collection of the American Friends for Spanish Democracy (AFSD) at the New York Public Library (NYPL), one picture stood out among the numerous priceless documents: three smiling children posing naturally for the photographer. Their carefree expression was not suggestive of the daunting conditions they endured at that moment. These children lived in a colony established during the Spanish Civil War in Torrent-Bo, an area located 20 miles northwest of Barcelona. It was the summer of 1938, and Vicente García Riestra, the 13-year-old boy in the middle, had become a foster child to the AFSD. The archival documents uncovered Vicente’s current life: his father, a butcher by trade, was now fighting on the Asturias front, in northern Spain. Along with his mother and four siblings, Vicente had left his hometown in Asturias and reached the children’s colony in Torrent-Bo, where the picture was taken. Under the “Personal Traits” category, Vicente’s description read: “small for his age, round face with a very puzzled expression; dark brown eyes and light brown hair. Very active and would like to study much more than play. Wants to become a chauffeur.” In the letter exchanges with his “padrinos” of the American Friends for Spanish Democracy organization, Vicente expressed the same wishes as any other child his age.

As a researcher of the Spanish Civil War, and a Spaniard who grew up amid deafening silence on this subject at home and school in the 1970s and 80s, I treasure these stories. Children’s voices are particularly stirring: in novels with young characters such as The Ravine by Nivaria Tejera, or First Memory by Ana Maria Matute, I imagine that these fictional characters shared my parents’ experiences during the war; their narratives filled a personal void of untold memories. Sitting at a century-old table in the Brook Russell Astor Reading Room for Rare Books and Manuscripts at the NYPL, I carefully examined every document in the folder, in an attempt to complete Vicente García Riestra’s unfinished story, to no avail. With low expectations to find information beyond the archive, and curious to know more about this child, I searched for him using a twenty-first century tool: I googled him. The search for answers proved much more fruitful than I could have imagined. Vicente was still alive—and he had lived an exceptional life since the Spanish Civil War.

An hours-old Facebook post published by the political party Izquierda Xunida de Siero, in Asturias, described the celebration that took place the same day, December 14, 2018. The pictures described a “tribute to Asturian Vicente García Riestra, survivor of Buchenwald concentration camp. Antifascist fighter and example of dignity.” The 93-year-old man holding his Nazi prisoner uniform in that Facebook post was indeed the 13-year-old smiling boy embracing his friends in 1938, unaware of his remarkable future.

I attached all the archival documents to the comments section of the Izquierda Xunida Facebook post, and asked if someone could send them to Vicente, as he probably would not have a copy of these records. Not long after, Edgar Cosío, the Izquierda Xunida Siero representative, contacted me, and put me in touch with Xuan Santori, the author of a recent book on Vicente García Riestra in the Asturian language. Santori sent me the copy of his book 42.553. After Buchenwald, a startling biography about the last Spanish survivor of the Buchenwald concentration camp, and one of the last Spanish survivors of the Holocaust. This book reveals the incredible life story of Vicente García Riestra. In masterly detail, it depicts the sequence of events that completed the story found in the archives.

Born in 1925 in Pola de Siero, Asturias, Vicente managed to arrive at the children’s colony near Barcelona with his mother and siblings. Franco’s forces executed his father, and one of Vicente’s brothers also died in the war. Vicente and his family were able to escape when the war was lost, walking across the border to France in 1939. During World War II, he joined the French resistance at 17-years old, and became a Gestapo spy. Captured and tortured, he was sent to die in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Against all odds, he survived 15 months of horror until the camp was liberated.

Today, Vicente is 93, and lives in Trélissac, France, where he is considered a hero. With much effort, he talks to students in elementary and secondary schools about his harrowing experience, so that “it never happens again,” said Xuan Santori. Yet he is unknown in Spain. Even today, due to a decree imposed during Franco’s dictatorship, he cannot regain his Spanish nationality.

We often think of archival research as a process to uncover former lives and completed historical facts. In my search for antifascist women activists during the Spanish Civil War, I found an accidental gift: the story of a man who changed history. Vicente García Riestra is alive today and he was able to look at his childhood picture from the Catalan colony with his son and granddaughters.

Increasingly, the Humanities face pressure to break down their walls and become more relevant to the general public. This story is a fitting example of the way an ordinary scholarly endeavor in a public archive can have a direct effect on the life of an extraordinary person. The unintended consequence of working in the archive, aided by the power of social media, provided a unique occurrence. Thanks to the role of organizations such as the American Friends for Spanish Democracy, the archives contain information about thousands of lives that need to be rescued from obscurity.

Xuan Santori will soon publish his book on Vicente García Riestra in Spanish, and he will include the NYPL documents. His text should be required reading for all Spaniards, because, in a country still divided, as Santori wrote, “to tell the story of one of those children is to tell the story of them all.”

María Hernández-Ojeda is Associate Professor of Spanish at Hunter College.