Sara Brenneis: “The Memory of Spaniards in Concentration Camps Has Essentially Been Shut Out”

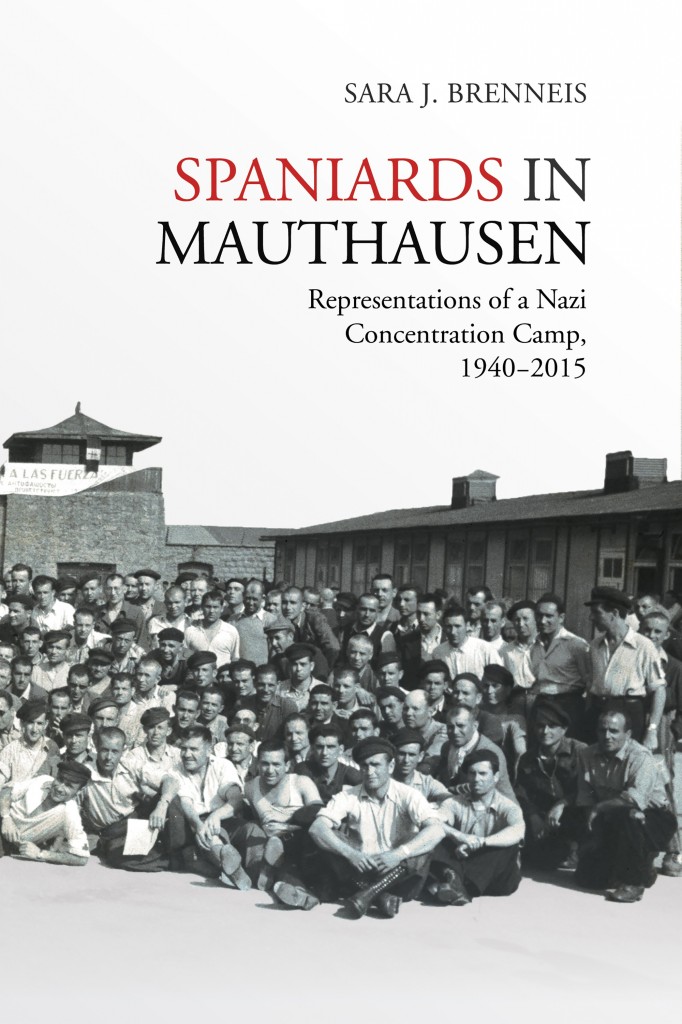

Few people know that the infamous Nazi concentration camp at Mauthausen was built by Spanish Republicans who were also its first inmates. This past May, Sara J. Brenneis, an associate professor of Spanish at Amherst College, published Spaniards in Mauthausen (Toronto), which discusses how the Spaniards’ camp experience has been narrated since 1940. This fall also saw the publication of the English translation of The Impostor, in which bestselling Spanish novelist Javier Cercas investigates the life of Enric Marco, a Catalan activist who for years falsely claimed to have passed through a Nazi concentration camp. An essay by Brenneis on Cercas’s controversial book was published this fall in the Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies. A good moment for an interview.

You show that the story of the Spaniards in Mauthausen was long hidden from public view. Would you say your own book is part, or symptom, of the changed way we—and Spaniards—look at the relationship between the Spanish Civil War and World War II?

SJB: Absolutely. In the book I look into how 10,000 Spaniards who fought for the Republic during the Spanish Civil War—or supported the Republic, because some of the deportees weren’t on the front lines—would only a few years later end up in Nazi concentration camps. After their experiences during the Civil War, they were committed anti-fascists in exile in France. As World War II escalated, they were captured by the Germans, who asked Franco what to do with them. The deportees’ political involvement and Franco’s disinterest in protecting them in any way doomed them to the camps. I think seeing the Spanish Civil War and World War II as one continuous international conflict is a perspective that still isn’t particularly understood, but these Spanish deportees to the camps are the embodiment of that continuity.

Why have previous narratives of the Spanish experience in Nazi camps been marginalized or forgotten when the evidence has long been available?

SJB: I was surprised as I researched this book at how many articles, books and films about this chapter of Spanish history are available—but you have to know where to look for them. There’s more out there about the Spaniards in Nazi camps now than in any other time in Spain’s history. But that doesn’t mean it’s gotten any easier to look back at the past and say: yes, Spain was active in World War II; Franco and Hitler collaborated; Spaniards were killed in Nazi concentration camps—and what more can we learn about what happened and the victims? Plus, the Spanish government hasn’t gotten involved in any meaningful way in recognizing or acknowledging its role, which really sidelines the whole matter both inside and outside of the country.

Your work straddles Spanish Civil War Studies and Holocaust studies. Are there major differences between those two fields—in academia or more broadly—in how they approach historical memory?

SJB: The central questions are largely the same: what happened, and how have we as a society remembered not only the events but also the individuals who were involved? And once the generation of people who actually lived through it have died, how do successive generations remember—and how do we assure that the memory lives on to educate the next generation about our shared past? But what’s absolutely true is that so much more work has been done on Holocaust memory than on memories of the Spanish Civil War—there have been many efforts by individuals, governments, cultural institutions to document what happened in the Holocaust, and it’s still ongoing. The Spanish Civil War has been investigated to a much lesser extent, though that has changed in the last 15 years or so. But the memory of Spaniards in the concentration camps—and Spain’s involvement in World War II—has essentially been shut out of both of these fields, Spanish Civil War Studies and Holocaust studies, which is in part why those memories are virtually unknown.

Your book came out three months before the U.S. edition of Javier Cercas’s The Impostor: A True Story, about someone who falsely claimed to have been imprisoned in a German concentration camp. How does Cercas’s book compare to the many other accounts of the Spanish experience in the Holocaust you’ve studied?

SJB: Well, the main difference is that Cercas’s book isn’t true—that is, the central story in The Impostor is about Enric Marco, who wasn’t actually in a Nazi concentration camp. And in that sense Cercas sensationalizes what are already incredible, life-and-death accounts of men and women who were deported to the camps. The books and memoirs I look at for Spaniards in Mauthausen are such immediate, personal accounts. They’re detailed, often painful, always moving stories of people who lived through unspeakable violence, who saw and experienced things that just seem impossible. But the difference is that their stories actually happened.

In a recently published article about Cercas’s book, you state that it is a “misplaced glorification of a false survivor.” Why misplaced?

SJB: Because there are thousands of stories of Mauthausen survivors, Ravensbrück survivors, Buchenwald survivors that have never been told. It’s a shame—given the fact that Spain as a whole is largely ignorant of this history—that Cercas picked someone who invented his background to be the subject of this book. But my point in the article I wrote about The Impostor isn’t just that I wish Cercas had written about an actual Spanish victim of the Nazis, it’s also that Cercas paints Enric Marco as a hero, a modern-day Don Quijote. I find that characterization to be unfortunate, to say the least.

How do you think The Impostor will be read in the United States, where the collective memory of the Holocaust is markedly different than Spain’s?

SJB: I suspect that more critical readers—those who have actually studied the Holocaust—may see it for what it is: the story of a false survivor. But for most people, the Holocaust is constantly reinvented in books and movies—I’m thinking of Sarah’s Key or The Boy in the Striped Pajamas. These stories are fictionalized, there are many aspects of them that are simply made up, but they are how larger audiences actually learn about the Holocaust. I suspect that Cercas’s book will land among these more popular portrayals of World War II and the Holocaust in the United States, though if we’re lucky, it may pique readers’ interests to find an account of an actual Spanish concentration camp survivor or to learn more about the history behind Marco’s falsification.

In your essay, you also express skepticism about Cercas’s claim that Spain’s historical memory movement is “dead.” What would you say are its major signs of life?

SJB: I’ll tell you what brings home this feeling that the historical memory movement is very much alive in Spain: the busloads of Spanish high school students who travel from Barcelona to Austria to take part in the commemoration ceremonies at the Mauthausen Memorial every May. Survivor groups like the Amical de Mauthausen and Triangle Blau, among others, organize these educational pilgrimages so that students without any personal connection to the camp can see for themselves where their countrymen and women were imprisoned and died. They learn the history in such an immediate way. Cercas ignores these grassroots organizations and movements in Spain to preserve the memories of Spain’s traumatic past, which are the lynchpins to Spain’s historical memory movement, in my opinion.

“The historical memory movement is very much alive in Spain.”

Studies have shown, you write, “that Spain rates last among European nations in terms of its population’s knowledge of the Holocaust.” What factors help explain this, you think?

SJB: Well, despite the extracurricular activities of the Amical de Mauthausen and other groups, students in Spanish high schools are simply not taught about the role their country played in World War II and the Holocaust. They may read Anne Frank, but how incredible would it be if they read something more relevant to them, like Joaquim Amat-Piniella’s K.L. Reich, a novel about the author’s experiences in Mauthausen, or Montserrat Roig’s oral history of Catalans in Nazi camps? These are home-grown materials that focus on what the Holocaust was and how Spain was involved—but they’re not part of the curriculum in Spanish schools. And certainly the fact that the Spanish government has never weighed in is another factor. I’ll be interested to see if Spain’s understanding of the Holocaust shifts at all as the story of the Spaniards in Mauthausen becomes better known—a new big-budget film, El fotógrafo de Mauthausen, comes out in Spain in October. It tells the story of Francesc Boix, a Catalan prisoner in Mauthausen I talk about in the book. Boix, who worked in the camp photo lab and brought photographic evidence of Mauthausen to the Nuremburg Trials, is becoming something of a folk hero in Spain. But for now, only a very small percentage of the population has a clear picture of what the Holocaust was and the role the Spanish government and Spaniards played in World War II.

“Only a very small percentage of the population has a clear picture of the role the Spanish government and Spaniards played in World War II.”

As the author of an important nonfiction—academic—book about the way the experience of Spanish deportees to Mauthausen has been represented in Spanish culture over the past seven decades, what do you feel about Cercas’s playful blurring of the line between fiction and nonfiction? It’s become his signature move.

SJB: I’ll be honest. As a reader, I’ve enjoyed Cercas’s books—he knows how to build tension around these “real stories,” as he calls them. But as a scholar of the Spanish deportation to Mauthausen, I’m much more conflicted about the way Cercas plays with fiction and history in his novels. Whatever sense of responsibility he feels—and I know he feels some, because he has written more earnest pieces about the Spaniards in Nazi camps elsewhere—flies out the window in the interest of a thrilling story in The Impostor. But I also think the only way to counteract Cercas’s imprecision is to make sure we continue to tell the true history behind these important historical moments—the Spanish Civil War, the Spanish deportation, the transition to democracy—because we share that responsibility as scholars, writers and filmmakers. Fiction writers dance between fiction and nonfiction—it makes for a good read—but historians and cultural critics should feel more of an urgency to stick to the truth. Of course, a good story is a good story—whether it’s invented or real. Cercas knows that.

Cercas, in his book, extols the work of academic historians and criticizes the way the witnesses, activists, and the media have “killed” actual memory by sentimentalizing and commercializing it. (“[T]he memory industry proved lethal to memory,” he writes in a passage you cite.) As an academic, where do you stand on the relation between the authority of scholars’ accounts and the value of other accounts?

SJB: I really think all of these accounts have value. Ideally, scholars give us a clear sense of the history and the context of the events. But other, more personal accounts give us a sense of how the topics we’re interested in as scholars are perceived in the real world, for lack of a better term. This is why I included so many different kinds of texts in Spaniards in Mauthausen: because the way people remember the past is colored by fiction, nonfiction, films, memoirs, even social media. When we look at these different materials alongside one another, it’s important to sort the invention from what we can corroborate as truthful, but those more commercial accounts can lend nuance to what might otherwise be a dry reporting of the facts. So, when I look a popular novel or a Twitter account that deals with the Spaniards in Mauthausen alongside a more academic text about the topic, I’m getting two sides of the story that often complement each other. This is how history comes to life, how it grabs people’s attention, and we can’t simply discount these popular works because they might not be wholly accurate. I’d hope that once someone gets interested in a topic like the Spaniards in Mauthausen from one source, they’d seek out another book or film to learn more. Eventually, perhaps they’ll land on a more academic source, but not at the expense of reading these rich and fascinating survivor stories.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College.