Book Review: Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War

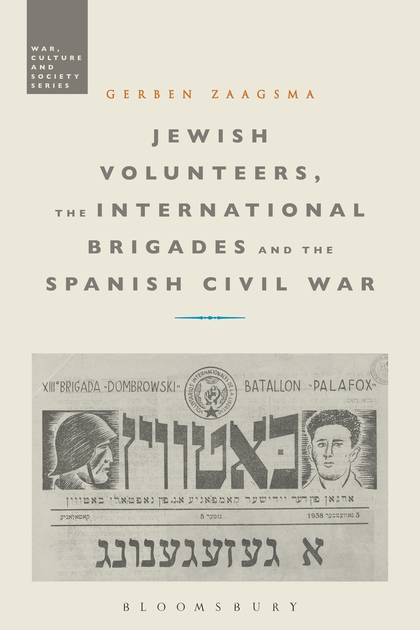

Gerben Zaagsma, Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Bloomsbury: London 2017; 250pp.

Among the 35,000 volunteers from over 50 countries who joined the International Brigades to defend the Second Republic, Jews were exceptionally plentiful: according to most estimates, they numbered between 4,000 and 8,000. Like their non-Jewish comrades, these volunteers left behind a wide range of materials—memoirs, personal correspondence, and interviews—that offer a complex view of their personal and national backgrounds, the events that led them to enlist, their experiences in Spain, and how the Spanish Civil War affected their lives thereafter.

The main objective of Gerben Zaagsma’s book is to explore how “a particular set of Jewish military experiences, both actual and remembered, became an expression of a process of emancipation and validation that were … integral to the project of Jewish modernity.” Zaagsma does this by “analyzing the participation of Jewish volunteers in the International Brigades and understanding its symbolic meaning both during and after the conflict.” The book itself, however, is less concerned with the experiences of Jewish volunteers and more focused on the symbolic and ideological meaning attached to Jewish participation in the Spanish Civil War among Jews and the other groups that went to Spain to fight.

By putting all volunteers of Jewish descent under the heading “Jewish volunteers,” Zaagsma acknowledges that not all volunteers viewed their ethnic and religious affiliation as the central motivation of their decision to join the International Brigades. He rightly notes that for many Jewish volunteers, class affiliation played an important role—a fact reflected in the generally high number of Jewish activists within left-wing movements during the interwar period. For most members of the Brigades, to volunteer was to express class solidarity and Jewish resistance against fascism (especially Nazism). But these two motivations occasionally came into conflict. As countless personal testimonies show, Jewish volunteers often struggled to reconcile religious, ethnic, and class identities. Yet the voice of the volunteers is not sufficiently expressed in the book, nor is this internal struggle, which outside sources (both Jewish and communist ones, for example) tended to downplay.

For the Paris Yiddish press, the Jewish participation in Spain became a myth of engagement and heroism—and a model to be emulated.

The first part of the book focuses on the formation of the International Brigades and the challenges faced by the group of Parisian Jewish communists (mostly recent immigrants from Poland) who lobbied for the formation of the Naftali Botwin Company. When the company was finally formed within the Polish Dombrowsky Brigade in late 1937, the majority of Jewish volunteers did not join. However, as Zaagsma shows, the Botwin Company not only became a key symbol of Jewish participation in the Spanish Civil War, but also emerged as a useful propaganda tool for the Comintern to present the Brigades as “a strong international brotherhood of men fighting fascism in Spain.”

The book’s second part is devoted to the representations of the Jewish volunteers in the Yiddish press of Paris, especially the Communist Naye Prese, as Zaagsma explores the changing profile of the Jewish community in Paris during the interwar years and the challenges it faced. He analyzes the ways in which different forces within the community viewed the events taking place in Spain and the manner in which they constructed a myth of Jewish engagement and heroism as a model to be emulated.

This third part examines the commemoration ceremonies, publications, and monuments of the post-war years, mainly between the 1960s and 1980s. As Zaagsma shows, these memory realms functioned as spaces in which post-Holocaust memory of Jewish participation in the defense of the Spanish Republic was reworked. As a result, the Spanish Civil War became an episode not just in Spanish history but also in Jewish history.

The final section of the book pays special attention to the discourse surrounding the role of Jewish volunteers in the Spanish Civil War and the organizational frameworks that emerged for the commemoration of these volunteers within the context of Israeli society and as part of the Zionist nation building narrative.

Zaagsma’s book is an important addition to the existing literature on the International Brigades and on the role of Jewish volunteers within its ranks. Its most valuable contribution, however, rests in the varied ways in which Jewish communities (both in the interwar period and following 1945) interpreted the struggle against fascism and their role within it.

Inbal Ofer is an Assistant Professor of History, Philosophy and Judaic Studies at The Open University of Israel. She is the author of Claiming the City/Contesting the State: Squatting, Community Formation and Democratization in Spain, 1955-1986 (Routledge, 2017), and Señoritas in Blue: The Making of a Female Political Elite in Franco’s Spain. The National Leadership of the Sección Femenina de la Falange,1936-1977 (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2009).

Hi Inbal,

I did not read the book yet.

I am interested in the history of Setty Abraham and wonder if you can add more.

See the article below, please.

https://albavolunteer.org/2018/09/far-from-baghdad-two-iraqi-volunteers-in-the-xvth-international-brigade/

Appreciate any comments from other people.

There is an article about Setty Abraham – in Spanish – here:

https://columnauruguaya.wordpress.com/uruguayos-en-la-guerra-civil/s-t/setty-abraham-horresh/