Book Review: A Distant Heartbeat: A War, a Disappearance, and a Family’s Secrets

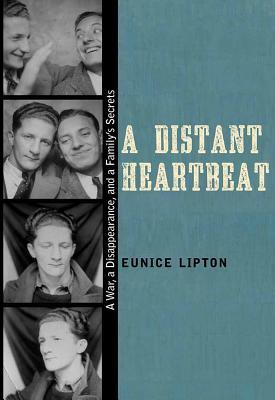

Eunice Lipton, A Distant Heartbeat: A War, a Disappearance, and a Family’s Secrets. University of New Mexico Press 2016, 176pp.

Dave Lipton died by sniper bullet near Gandesa, on Hill 666, at the end of the Ebro offensive. His niece explores the enigma her uncle’s passage to Spain, her father’s role in keeping Dave’s voyage secret, and the silence that fell over her family after his death. A story of fraternal betrayal.

Eunice Lipton saunters toward a Parisian Bistro. From my table I watch her slide across the pavement and pause on the threshold of the terrace, a panama hat perched over her short straw-grey hair. Lipton moves like a danseuse, snappy and sinuous at once. An art historian, Lipton has published on Degas, famous for his depictions of ballerinas and women workers. In both her scholarly and her autobiographical writings, the intertwining of the gendered body, ideology, and emotion figure prominently. Perhaps this attention to the body in motion emerged from her family of great dancers, and the furtive, sinister dance of political commitment, adoration, and betrayal among her Jewish immigrant relatives that is the subject of her memoir A Distant Heartbeat: A War, A Disappearance, and A Family’s Secrets.

I have been largely alone in Paris, working in archives by day and eating each night with the delicious companion of French Seduction, Lipton’s 2007 memoir about her family history and her connection with France, which includes a moving analysis of her troubled relationship with Louis Lipton—her narcissistic, charming, Francophile father whose relationship with his daughter hovered at the edge of sexual creepiness. She also explores the legacies and realities of anti-Semitism in France and the intersections of love affairs, ideological dreams and the challenges of acculturation of New York émigré Jews.

Our Paris lunch takes place during election season back in the USA. We spend our meal wringing our hands over the Trump candidacy, which has provoked in Lipton an intense unease. I try to part with words of reassurance that November will bring the first woman to the White House. Lipton, a feminist with a keen eye for misogyny, seems to know better. As I watch her depart, I observe in her posture, at the confident juncture of her back at her hips, the reverberations of the “heartbeat” that gives title to her wrenching memoir about her uncle, Dave Lipton, whose secret participation in the Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War would hold agonizing consequences for more than one generation of his family.

A Distant Heartbeat is, on one hand, the account of the prelude and the aftermath of a soldier’s death in combat: Dave Lipton died by sniper bullet near Gandesa, on Hill 666, at the end of the Ebro offensive. The book, however, covers vast emotional, cultural and geographical territory moving from the Latvian Jewish immigrant world of 1930s New York to the barren hills of Sierra Pandols to the last great gatherings of surviving veterans of the International Brigades at the end of the twentieth century. Lipton captures the intimacies of Bronx immigrant kitchens and the neuroses of entangled Jewish family relations, while imagining the how volunteer fighters foreign to Spain lived moments of powerful camaraderie interspersed with periods of boredom and misery.

The book includes two intertwined novelistic memoirs of suspense, the first of which features Eunice in the role of sleuth. Undeterred over more than two decades, she pieces together the story that comprises the second story: the enigma of Uncle Dave’s passage to Spain to join the International Brigades, her father Louis’s role in keeping Dave’s voyage secret, and the silence that fell over her family after his death.

Uncle Dave came at first to young Eunice, her brother and cousins as a phantom, trapped in an old box of photos, curiosities and letters, squirreled away in a drawer at her grandparents’ home. Decades later, through extensive archival research and tracking Dave’s friends and former comrades Eunice Lipton reconstructed some of his past—the loving son, the sexually ambiguous young man nevertheless adored by women, an active member of the Young Communist League in New York, and the volunteer with the Lincoln Brigade. Fashioning Dave’s history through often sparse and contradictory clues, she creates an important and complex composite of a Lincoln volunteer, one who lived the 1930s and Spanish Civil War as an opportunity to act in accordance with his communist convictions. She also presents the Spanish Civil War for Dave as an almost carnal experience of the emotional and bodily desire to meld with one’s comrades in the struggle against fascism.

A Distant Heartbeat likewise concerns itself with the Lincolns as a source of inspiration for later generations of progressives. In the process of her investigation, Eunice presses her father for information:

’Why do you care about all this?’ he asks quietly. …

Why do I care? Because my uncle was brave? Because his decision enthralls me, the journey intrigues me, the optimism amazes me?”

Through the recovery of the life story of this one volunteer, the memoir rehearses the many reasons why the history of the Lincolns never gets stale; it evinces a tight, intense narrative energy and antifascist ethos that continually inspires and enchants.

Why had Dave Lipton’s death in Spain remained an open wound, a taboo subject that left Eunice’s grandmother sobbing at night behind closed doors? Why was her father Louis so defensive when Eunice asked to know more about the uncle she had always intuited was like her? She tells a story of fraternal betrayal.

In the spring of 1938, Dave Lipton (born Lifshitz) told his parents he was taking a job in the Catskills. Instead, he boarded the SS Manhattan destined for Le Havre. Passing through Paris, Dave and a group of other volunteers eventually made it to the Franco-Spanish border, taking the perilous trek across the Pyrenees by foot. In the early summer of 1938 an important, if ill-fated, Republican offensive was about to begin, including the famous Battle of the Ebro. Hill 666 would be one of the final sites of this battle—and the last place Dave Lipton touched the earth still with life. Before his comrade Bill Wheeler could shout to him to keep his “head and fanny” low, a sniper took Dave down. Eunice, his postmortem autobiographical voice, strives to imagine what Spain meant to Dave: “Until the sniper gets Dave, he may never have felt as whole before, absorbed in this world of fear and ecstasy and unreflective action . . . all in the interest of saving people from their appalling destinies as he reaches for his own.”

Once in Spain, Dave had decided to confess the truth of his whereabouts to his parents. He penned letters asking for their forgiveness, beseeching them to write to him, requesting packages of chocolate. Dave also wrote to his parents about the reasons why he left: “If you would see the hundreds of children poverty-stricken. Hundreds of mothers grieving… You would understand why I came here to help them.”

Back in New York, his brother Louis would be forging his own appalling destiny by intentionally keeping Dave’s battlefront letters from reaching his parents. Louis, the frenetic, egotistical, competitive son, never allowed his parents to see the letters, missives that increasingly expressed Dave’s desperation to hear from his mother and father. As the months wore on, the Liptons went on believing their son was in bucolic upstate New York, waiting tables.

In December 1938 Louis received word that Dave had fallen in Spain. He thought contemptuously that Dave “threw his life away.” His game was up, though, and Louis had no alternative other than to confess the truth to his parents. The purloined letters ended up in that shoebox, buried in the back of a drawer. Years later, they would become Louis’s revered object, one he would bend over “like a mother over a cradle, the sorrow and the emotional display, but also the contempt.” Eunice writes that this “overworked choreography… got under [her] skin.”

Nevertheless, it was the overwrought contemplation of that mysterious crucible of letters that set Eunice on her path as family detective. One question never fully disclosed by the book is why. Why did Louis interrupt the correspondence between a beloved boy and his parents? Might Louis, the boxer, have felt his masculinity threatened by the “soft boy,” the marshmallow brother who was actually brave enough to go off to battle? Was Louis partially responsible for Dave’s death on Hill 666? “It’s possible that if Dave had heard from his parents,” Lipton writes, “he might have been more alert. .. He might have taken fewer chances.”

These are among the many questions that the memoir posits for the reader’s consideration. Like the dangerous reliquary of Dave’s letters, the memoir itself becomes a repository of trauma and mystery that can only be partially untangled, a pas de trois in which Eunice, her father and her uncle continue to circle around one another, each seeking in the reflection of the others a nod of remorse, a confirmation, an expression of pride.

At the very of end of the memoir, Eunice describes the intense “sorrow, desperation, shame” that Louis felt after Dave’s death. But the daughter and the niece of these men, having unraveled the web of intrigues around her uncle’s abbreviated life, stands elated and energized alongside the memories of such terrible heartache: “As for me, well, sitting there, I am so proud of Dave, so very proud that he was one of us, my family. I know how much his young life gave me. Without him and his friends, people like me never would have poured out onto the streets against the war in Vietnam, ridden the buses and marched for civil rights, created the women’s movement and the gay liberation movement.”

Gina Hermann is the Vice-Chair of ALBA and an Associate Professor of Spanish at the University of Oregon.

I would like a copy. Do you send to The Netherlands?

Thanks for that fascinating story. I will try to find the book.