“Who the hell worked out a plan like that?” New Light on the 1935 Bremen Riot

When the Bremen, a German luxury ship proudly flying the Swastika, was ready to sail from its berth at Pier 46 in New York, two seamen who later volunteered to fight in Spain managed to fool the crew and rip down the Nazi flag. In the archives, Dan Czitrom came across a deserter’s testimony that fills out the story.

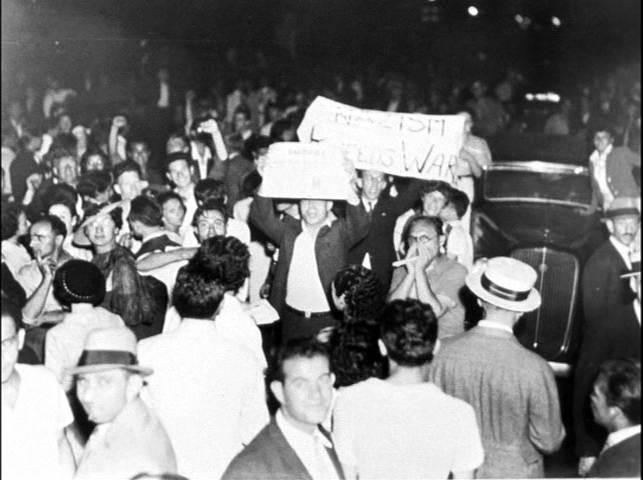

While doing research into State Department files at the National Archives, I recently came across a curious document that provides a fuller picture of the so-called Bremen riot in 1935. The 1,200 passenger German luxury ship, proudly flying the Swastika, was ready to sail from its berth at Pier 46 on 46th Street in New York on July 26. A group of Communists, including two seamen who later volunteered to fight in Spain, planned and executed a daring dash to the bowsprit, ripping down the Swastika and sending it into the Hudson River. Thousands of sympathetic demonstrators cheered and a full scale riot broke out on the ship as New York City police struggled to restore order. One detective was beaten, one of the conspirators was shot, and six men were arrested. The incident made the front pages of New York newspapers and led to a diplomatic crisis between Hitler’s government and the United States.

Thousands of sympathetic demonstrators cheered and a full scale riot broke out on the ship as New York City police struggled to restore order.

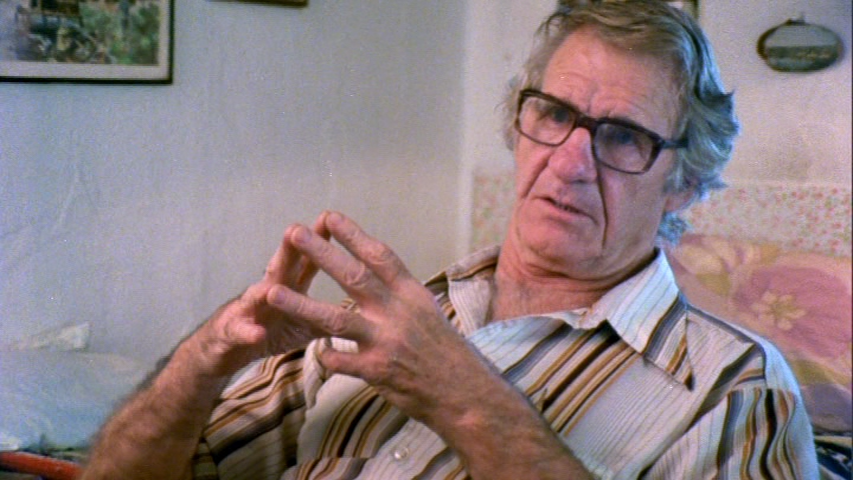

In the 1982 documentary The Good Fight, seaman and Lincoln vet Bill Bailey offered his colorful first person account of how he and two others raced across the ship, pushing through startled German crew members, and, after a few anxious moments with an uncooperative rope, managed to cut down the hated symbol of Nazism. The Bremen incident galvanized anti-fascist and Popular Front activism against the menace of Nazi ideology.

One of Bill Bailey’s accomplices was another seaman, William Jamieson, who went by the name William Howe when he volunteered for the Lincoln Brigade in 1937. Born in 1908 in Michigan, Howe had joined the Communist party in 1934, organizing seamen in Seattle, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and other cities. He was recruited to go to Spain by fellow seaman Harry Rubin and future Lincoln commissar John Robinson. But Howe quickly soured on his experience in Spain. When Bill Bailey met up with him there Howe grumbled angrily about military discipline. He left the front lines more than once and visited the American consulate in Barcelona seeking repatriation. After the battle of Belchite in September 1937, he deserted the front for good and disappeared from the world of radical activism.

By June 1938 Howe had made his way back to New York, where he was interviewed by a State Department special agent and a NYPD detective. The stenographic account in the archives is a long, rambling, sometimes contradictory narrative of Howe’s life in the labor movement, the Communist party, and his time in Spain. In a cover note, the State Department explained it was most interested in Howe’s “disclosures regarding the actual methods used in sending American citizens abroad for military service in Spain.” Howe obliged them by detailing the use of fake or stolen passports and birth certificates. He renounced his work with the Communist party and his decision to join the Lincolns. “After you get to Spain, things start to change,” he told his interviewers, “you find out the score. You don’t go there to be dictated to as a volunteer, believing you are going to fight for Democracy. That’s what I went there for—not to fight for Stalin but for principles, but it turned out different.”

We can only imagine the questions Howe was asked and the promises (or threats) made by his interviewers. But he did everything he could to distance himself from his former life and comrades, and for good measure he embraced a deeply anti-Semitic interpretation of his plight and of the Bremen affair: “The Russian Jews are behind the Communist efforts to recruit men to fight in Spain and supply the finances…Their modus operandi is somewhat similar to that shown in the Bremen case, where they got a number of us fellows—Irish and Christians—to start trouble, concealing the fact that the Jews were responsible for it.”

Here is Howe’s account of his role in the Bremen riot:

In 1935 in the month of July, around July 18th, I met Eddie Gillette [Edward Drolette] by the Workers Book Shop on Broad Street, New York. He approached me and asked how I would like to go on a job. I asked what kind of a job and he said: “I cannot let out the information now. Be on the job and have a suit of clothes and look respectable.” I asked what the job was and he said: “We are going on the Bremen, just walking around.” I asked him about it and he told me about [Lawrence] Simpson, who was arrested in Hamburg, and being seamen we were going aboard the Bremen and just protest with our voice. Well, I couldn’t see why they should just take a seaman off the boat in Hamburg and arrest him and throw him in jail. A week later, it was around the 24th or 25th, [William] McCormack approached me in the New China Cafeteria on 14th Street off Broadway. McCormack said: “Do you know what the score is? I am supposed to go up and pull down the Swastika and you fellows make a passage for me to get off the ship.” I asked how many are in on it and he said “fifty seamen” and that we are going to make Hitler release Simpson. That suited me all right. I said: O.K.

On the 26th of July, Friday night, we met up here in the Workers Cafeteria Union—the Food Workers Industrial Union away uptown. We met there and they gave us our instructions. We were supposed to go aboard the ship in twos and threes and perform this demonstration. We went aboard the ship and hung around. Every once in a while the guide would say, “What’s the password?” It was 11:45. At that time he was to make the dash to pull down the Swastika. He never got there. At 11:45 the signal was given—McCormack was knocked cold—the works went off—McCormack was knocked cold before he got there. Daly [Bill Bailey] and [Arthur] Blair, they pulled down the Swastika and threw it in the North River. I got near Gillette when he was shot by Moore of the Police Department. At that time I was wrestling with a Heinie, who was twice as big as myself. I was arrested and put in jail and bail was fixed at $2,500, but later reduced to $1,000, and I was released on $1,000 bail. Vito Marcantonio was my attorney and he was assigned to defend us by the International Defense. We thought we were fighting for Democracy. We didn’t think it was Democracy to take a seaman off a ship and arrest him and that was our way of having Simpson released. It was great publicity for the Communists and they made a lot of money in extending their Communistic propaganda. I gathered this after the thing was over. I haven’t quite got over the effects of the beating I got on that ship. Then I was fully convinced that there was no justice in the United States! I had no use for the police—I was always getting in a jam for something I thought was right. I wasn’t a Red Hot Bolshevik—I opposed a lot of their program and because of that in Spain I was sentenced to be shot. Americans are misled by their propaganda. Their minds are not what they would be if they had a job and the Communists take advantage of that.

Howe’s version essentially supports the story Bill Bailey told in The Good Fight and in his memoir, The Kid from Hoboken. Other sources—the official NYPD report, press coverage, a Communist party organizing circular, and court records—give us more context and underscore the international uproar that followed. The plot evidently originated with a small group of Communist seamen, including Bailey, outraged by the recent arrest in Berlin of fellow American seaman Lawrence Simpson, who had been thrown in jail when he was found with anti-fascist literature meant for distribution in Germany. The local Communist Party club on Tenth Avenue, which included many seamen and dockworkers, issued a circular announcing a protest demonstration. Addressed to “Catholics of New York” (perhaps a nod to the neighborhood’s largely Irish population), it also called for Jews, Communists, and all anti-fascists to unite against Hitler and fight for civil and religious freedom in Germany. Local police had received a copy of the circular through an informant, and they showed it to the head of the Hamburg American Line. But the line rejected the NYPD’s plan to have cops on board the ship; it relied instead upon fifty uniformed private detectives. The NYPD sent 50 officers and ten mounted police to patrol the demonstration to be held on Pier 86.

The plot evidently originated with a small group of Communist seamen, including Bailey, outraged by the recent arrest in Berlin of fellow American seaman Lawrence Simpson.

The original plan cooked up by the local CP leadership called for Bailey, Howe, and about a dozen other men to dress in suits and board the ship while pretending to visit with relatives about to depart. (The ship charged ten cents for this privilege, and each of the men was given a dime to cover it.) As soon as the “all ashore” whistle blew, signaling for visitors to leave the ship, the idea was for the men to form a corridor to the bow, have one or two of them rush up and grab the Swastika, and then bring it ashore for the demonstrators to pour gasoline on and burn. But the veteran seamen were skeptical. “Who the hell worked out a plan like that?” Bailey asked. “Some lunkhead who never saw a ship before, I suppose,” answered another.

Meanwhile, the raucous demonstration on shore had grown to thousands, with people carrying placards and banners, and chanting anti-fascist slogans. When the “all ashore” whistle blew at 11:40pm, the men went into action. But with German officers on alert for trouble, and with dozens of private cops on board, they were forced to scrap the plan and improvise. One group worked its way up the starboard side to the bow, distracting the crew and cops, while a trio of men made for the bow on the portside, intent on pulling down the Swastika. Seaman William “Lowlife” McCormack knocked out a German officer who questioned the men, and then was beaten himself by an NYPD detective. Bailey, with the help of fellow seamen Arthur Blair and Adrian Duffy, finally managed to cut the Swastika down and send it fluttering into the Hudson River. Bailey, Howe, and four other men were arrested, including Eddie Drolette who was shot in the thigh by a police detective. The arrested men were “worked over” by cops on the pier and then taken to the Eighteenth Precinct station near 47th St. Outside, a boisterous crowd of 1,000 demonstrators shouted in unison, “Free the arrested seamen!”

“Who the hell worked out a plan like that?” Bailey asked. “Some lunkhead who never saw a ship before, I suppose,” answered another.

A diplomatic firestorm followed. The German Ambassador to Washington protested emphatically to the State Department, demanded an apology for a grave insult, and called for severe punishment of those found guilty. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, noting the ship’s owners had rebuffed the NYPD’s offer of help, refused to offer any apology. President Franklin Roosevelt declined to comment directly on the affair, but he made it known that he sympathized with protests by American Jews against Germany’s religious repression. In early September, City Magistrate Louis Brodsky poured more fuel on the fire when he dismissed the charges (felonious assault and unlawful assembly) against Bailey, Howe, and their confederates. Brodsky, a Jew himself, wrote a courageous decision denouncing Nazism, noting “the regime, represented by the swastika, supports a merciless war against religion, against freedoms. The regime steals the elemental rights from people solely on the grounds of their background and religious beliefs.” The Bremen affair was provoked by “this flaunting of an emblem to those who regarded it as a defiant challenge to society.” The press secretary for the pro-Nazi German American Bund, outraged by Brodsky’s decision, called it “another proof of the world-wide Jewish-Communist conspiracy against new Germany.” Secretary of State Cordell Hull sent a note to the German government expressing “regret” over Brodsky’s ruling.

The press secretary for the pro-Nazi German American Bund, outraged by Brodsky’s decision, called it “another proof of the world-wide Jewish-Communist conspiracy against new Germany.”

On September 15, the German government proclaimed the Swastika banner, previously the symbol of the Nazi party, to be the sole flag of the German Reich. It also approved new legislation stripping German Jews of citizenship and banning intermarriage between Jews and Gentiles. In his speech to the Reichstag, Hitler referred directly to the Bremen incident and Magistrate Brodsky—“an illustration of the attitude of Jewry toward Germany”—as a justification for the new so-called “Nuremberg Laws.”

Daniel Czitrom is an ALBA Board Chair Emeritus and the author most recently of New York Exposed: The Gilded Age Police Scandal That Launched the Progressive Era.

I met Bill Bailey, of San Francisco, many years ago when he brought the film “The Good Fight”, shown at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, Brown Auditorium. He made an excellent presentation prior to and after the showing. I complimented him and thanked him for having fought against fascism in Spain. For a few years we were in contact by mail. I remember he was a very tall and obviously a very physically strong man, so I would think that it took quite a few NYPD and Nazi crewmen to beat him down.

[…] longshoreman who joined the CP at an early age while working as a Longshoreman. He was part of the storming of the Nazi ship Bremen when it visited the NYC harbor in 1934 cutting the swastika banner from the post and tossing it into […]