Jewish Volunteers in the International Brigades: What Drove Them?

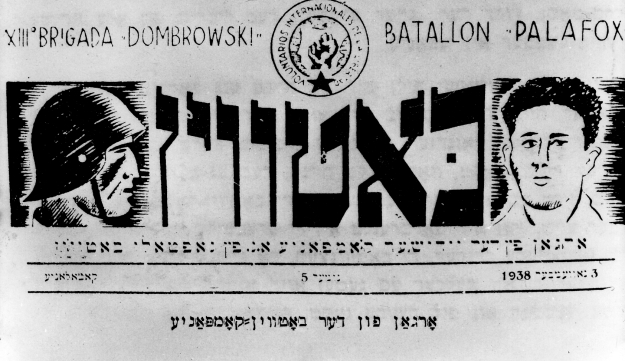

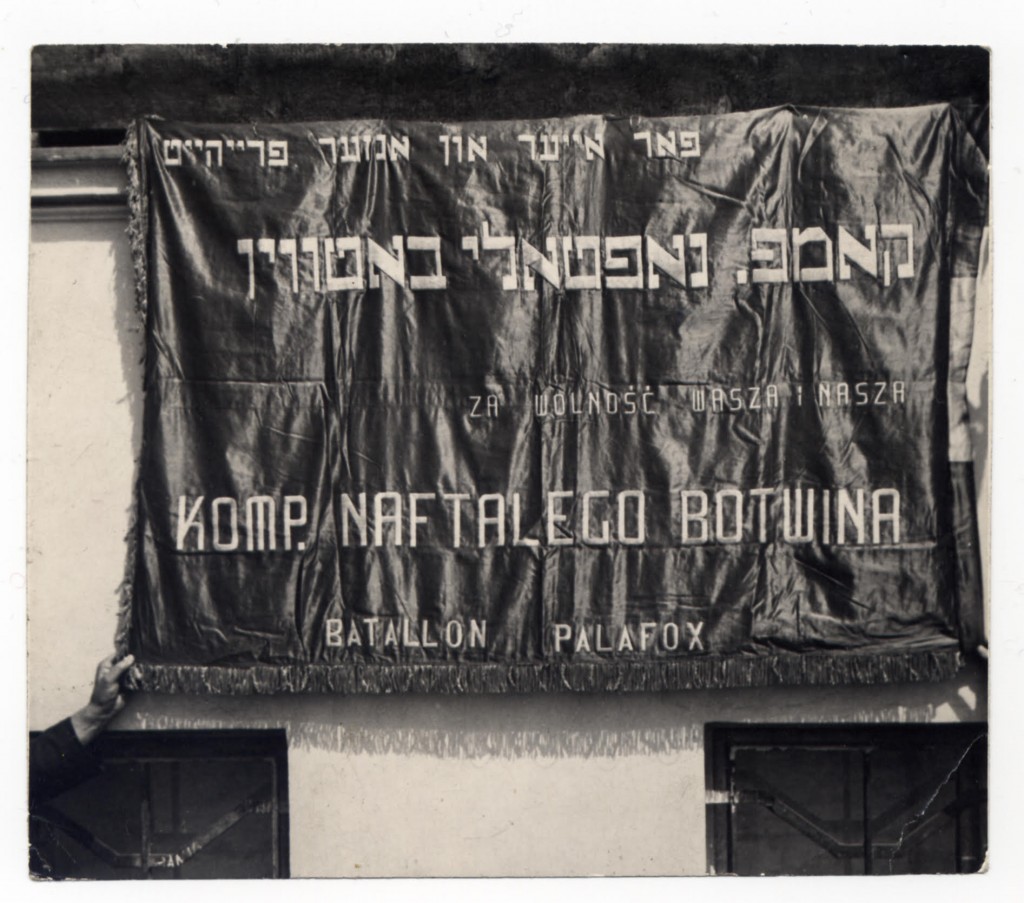

The tens of thousands of volunteers who joined the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War included a relatively high percentage of men and women of Jewish descent. But can we say that these volunteers were driven by a specifically Jewish motivation to fight fascism in Spain? Or did their presence simply reflect the relatively large number of Jews active in the Socialist and Communist movements in certain countries at the time? And if the latter is the case, what explains the creation of the Naftali Botwin Company—a Jewish military unit within the Polish Dombrowski Brigade that was founded in December 1937 upon instigation of Jewish communists in Paris, most of them migrants from Poland?

Many writings on Jewish volunteers in Spain not only emphasize their high number in the International Brigades but use the Holocaust as the main prism to explain their participation. Since many in the brigades had not only come to Spain to fight Franco but also his fascist allies Hitler and Mussolini, the struggle of volunteers of Jewish descent is often presented as the first act of Jewish resistance against fascism, fascist anti-Semitism and, ultimately, against the Nazi extermination policy that culminated in the Holocaust. Against the background of post-Holocaust debates about wartime Jewish responses and behavior, much of the literature inscribes the participation of Jewish volunteers in the brigades in a larger resistance narrative. The main purpose of this narrative is to counter the myth of Jewish passivity in the face of the Nazi onslaught.

The postwar memory of Jewish volunteers in Spain, in other words, was decisively shaped by the Holocaust. But how did Jewishness and Jewish concerns matter during the Spanish Civil War? Why was the Botwin Company actually created? And what does it mean to speak about “Jewish volunteers” to begin with? In my research, I purposely use this phrase to refer to all volunteers who were born Jewish, without assuming that their Jewishness carried over into the motivation with which they fought in Spain —or indeed, that a particular level of Jewish consciousness underpinned their participation. In fact, for many of the Jewish volunteers this was not the case; theirs was an ideological, not an ethnic, choice.

The history of the Botwin Company should be seen within the context of Jewish participation in the Communist and Socialist movements, particularly the activities of Jewish migrant communists in Paris in the interwar period. Given the important role that the Brigades played in the Comintern’s campaign for the Popular Front, propaganda was an important factor for the company’s formation. A Jewish military unit facilitated support campaigns for Spain among Jewish migrants in France, for example.

Inscribing the participation of Jewish volunteers in the brigades in a larger resistance narrative helps counter the myth of Jewish passivity in the face of the Nazi onslaught.

Yet there was another crucial reason for the company’s creation: the existence of anti-Semitic stereotypes about “Jewish cowardice.” These stereotypes had a long history and were grounded, among other things, in allegations of Jewish draft evasion. Against the background of nationality politics within the brigades and the occurrence of anti-Semitism within its ranks, concerns about Jewish/non-Jewish relations played a central role in the company’s formation. Created within the Polish Dombrowski Brigade, the Botwin Company served to emancipate Jewish volunteers as worthy soldiers, equal to their Polish comrades in arms, just as Jewish soldiership in general had always been linked to the project of emancipation.

Dombrowski Batallion swearing allegiance to the Republic before the withdrawal of the International Brigades, 1938. Photo Zofia Szleyen. Public domain.

It’s true that we can’t speak of a specific category of Jewish volunteers within the International Brigades, motivated by distinct Jewish concerns and animated by a clear Jewish consciousness. Nonetheless, we can’t understand their experiences, during or after the Spanish Civil War, without addressing the two great myths that have loomed so large over their participation and legacy: that of Jewish cowardice, and that of Jewish passivity during the Holocaust.

Spain might not have been the place where a singular category of Jewish volunteers fought a battle against the future murderers of their people; but it was the site where they fought one of the classic anti-Semitic stereotypes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: that of the Jew as a coward. The example of the Botwin Company shows that Spain became a battleground to achieve inclusion and emancipation. In that sense, the experiences of Jewish volunteers, whether they were self-consciously Jewish or not, constitute one of the many chapters in the ongoing project of Jewish modernity as it unfolded from the late eighteenth century onwards.

Gerben Zaagsma (http://gerbenzaagsma.org) is a senior researcher at the Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH) of the University of Luxembourg. His Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War was published earlier this year by Bloomsbury Academic.