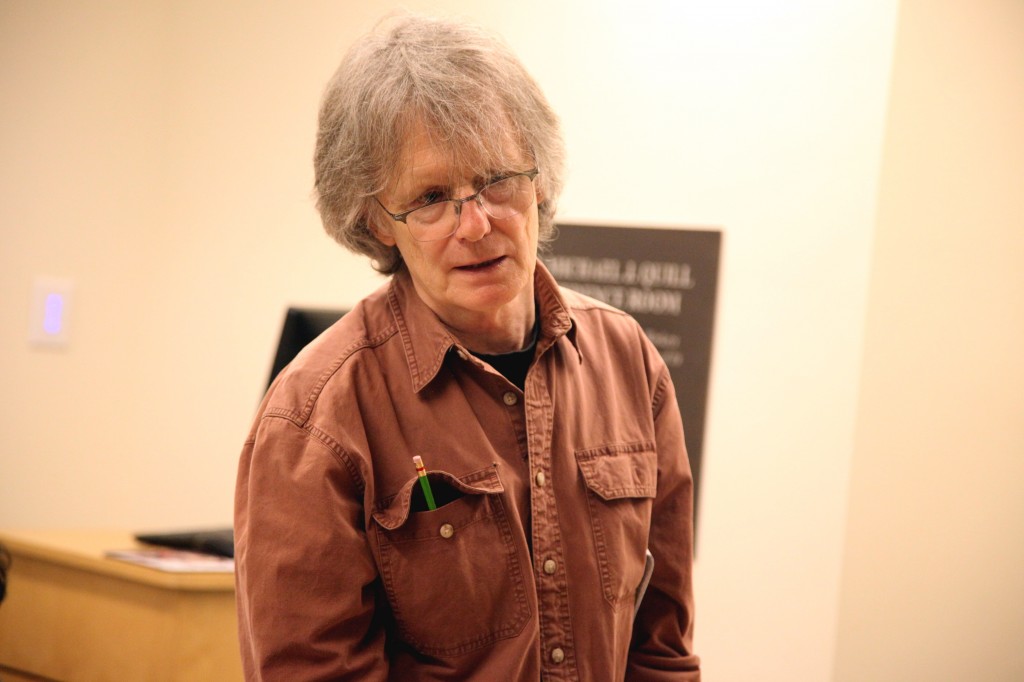

Faces of ALBA: George Snook, Brooklyn History Teacher

George Snook is an award-winning history teacher at the Packer Collegiate Institute in Brooklyn, New York. For over 25 years he has inspired his students to engage history by doing their own research. The Spanish Civil War and the experiences of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade play a central role in his classes. An alum of multiple ALBA institutes, Snook introduces his students to history and the Spanish Civil War using materials made available by ALBA and the Tamiment Library at New York University.

Your family has a history fighting fascism. Could you please tell us about that? How did this historical experience shape your understanding of history?

My father served as a medic in the 45th Division of the U.S. Army. In the spring of 1945, they liberated Dachau Concentration Camp. In 1962, to impress upon me the importance of vigilance and resistance to totalitarianism in any form, he took me to Dachau to see first hand the evidence of Nazi crimes against humanity. As a teacher of history, I want my students to confront the past in a way that surveys courses do not permit. History can and must provide students with tools to make sense of the world and influence its future.

I want my students to confront the past in a way that surveys courses do not permit. History can and must provide students with tools to make sense of the world and influence its future.

How do you integrate the Spanish Civil War and the Lincoln Brigade into your curriculum?

For two years the archives have served as the foundation of a second semester research project in Advanced Topics in European History. I wish students to develop the skills of historians— to compose papers drawn from the raw material of the past. To this end I devote six weeks of the course for students to dig into archives and compose research papers based on them. Handling and studying original documents and artifacts offers the student a unique opportunity to develop an idea that he or she can defend with reason and evidence. The Spanish Civil War is inherently interesting to students as the narratives of the volunteers raise questions about courage, sacrifice, and commitment to a cause. When the history is presented to students through contemporary letters, newsreels, newspaper articles, and posters, the desire to go deeper is immediate, sincere, and sustained. Working with archival materials allows the students to engage in a process of discovery. The documents prompt questions, and the search for answers drives the research. New York City students are particularly excited when they realize that so many of the young men and women hailed from familiar neighborhoods.

You are known for getting your students to work their way through archival material. What materials do the students read?

After spending several days on the political and social background of 1930’s Europe, students are introduced to the archives. Students can access most of what they need through ALBA’s website. They learn to navigate the database and explore the letters, posters, drawings, photographs, interviews, and links they require. Students also locate sources in the archives of newspapers and magazines, university collections, and scholarly publications. It is important that they consult lengthier works as well, so we have gathered a modest, but worthwhile collection of books on the Spanish Civil War that students may use.

What have you gained from the ALBA teaching institute? How many institutes have you attended?

For too long history courses and textbooks have neglected the Spanish Civil War. Students find its themes—the clash of 20th century ideologies, the impact of war on civilians, resistance to authoritarianism, and the struggle for justice and democracy—compelling. In the past, I have used Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia to introduce students to the Spanish Civil War. When I attended my first ALBA teaching institute, I realized I could transform a modest unit of study into an archival research project. The two sessions I have attended have been an inspiration for much of the work I now do in the second semester. The sessions offer a variety of materials and approaches to the archives that have proven to be of enormous value in my work.

What themes do you emphasize when you teach about the Spanish Civil War?

Once the historical background is firm, I introduce the students to the archives. This year New York University archivists welcomed my students to the collection [at the Tamiment Library] and instructed the class in the use of finding aids. Pairs of students then selected a general topic to investigate from the following categories: 1. Writers and observers of the Spanish Civil War, 2. Men and women who served in the International Brigades, 3. The relationship of the war to civilians, and 4. The Spanish Civil War and the shaping of public opinion. From this starting point, students began their research and soon narrowed their focus according to their personal interests. Several chose to research African-Americans or women who served in the Brigade. Others were drawn to propaganda, how it was created, and how it works. Several chose to study the influence of journalists and writers on shaping American opinion and policy. I try to give students the tools and the materials, but want them to investigate what they find most interesting.

How do your students relate to the themes of the Spanish Civil War?

Students are drawn to thematic content that directly addresses issues of race, gender, human rights and social justice. With little prompting, students connect the issues of the 1930’s to what they see and read every day. They are eager to make sense of their world, and the records of the volunteers offer a window into how an earlier generation confronted challenges to freedom and justice. Learning directly from letters and photographs makes for especially powerful instruction. This year the connections were particularly vivid as Packer Collegiate Institute hosted an exhibition of photographs shot by Syrian children in Jordanian and Iraqi refugee camps. The students immediately saw parallels to the drawings done by Spanish children that they saw in the Ben Leiter collection and in They Still Draw Pictures. Two of my students helped curate the gallery show, and the class was eager to share their observations with Dr. James Fernandez and Andrés Fernandez when they visited Packer and viewed the exhibit.

With little prompting, students connect the issues of the 1930’s to what they see and read every day.

You also have an oral history project for your students.

The oral history project has become the culminating feature of my New York City history course. Since immigration and cultural diversity have shaped every neighborhood in the five boroughs from the 17th to the 21st centuries, I thought it appropriate that we study the interaction between natives and migrants in New York City today. I suppose living in the Lower East Side of Manhattan for thirty years and taking students on tours of countless immigrant enclaves prompted me to come up with this project. Students work in pairs, develop questionnaires, conduct two filmed interviews, and edit and submit them as their final work of the semester. Students must interview one migrant and one native New Yorker. It’s fascinating to see how natives and migrants understand the city and its character in similar and different ways. Given the political climate today, I think it is especially important to recognize the contributions of new arrivals to the culture and fabric of the city. Students have interviewed neighbors from a wide variety of countries including Yemen, Russia, Italy, Mexico, Guyana, and Australia, to name a few.

Fortunately, Packer boasts several excellent film classes, so some of my students incorporate camera angles, sound, and roll footage into their work quite effectively. By and large, I concentrate on the quality of their questions and how they draw out the stories that bring their subjects to life. My hope is to assign these interviews for as long as I continue to teach. I love how they collectively illustrate what is fundamental to the city’s character.

Aaron Retish teaches at Wayne State University.