Hostages of Appeasement: Jay Allen on Refugees

Do refugees have rights? If so, who is responsible to protect them? These contemporary questions are not new. Indeed, they were raised eloquently by the American journalist Jay Allen in November 1939 in Survey Graphic, a monthly magazine edited by Paul Kellogg, illustrated with images by Ione Robinson (1910-1989), an American photographer and artist. Allen (1900-1972) had reported the atrocities committed by Franco’s armies during the Spanish Civil War for the Chicago Tribune. He well understood the perils facing Spanish refugees who had fled to France. He himself would be imprisoned by Hitler’s German officials after the fall of France in 1940. We can ask today, as he did then: What can Americans do?

“The experiment which opened to such bright hopes in the spring of 1931 has been destroyed . . . chiefly by the fact that it was born into a fiercely illiberal world which betrayed it at every step.” —New York Herald Tribune, February 7, 1939.

Resurrection of the Spanish Republic is not on the war program of the Allies.

Mr. Chamberlain has expressed his regrets to Czechoslovakia and to Poland and promised them that they will rise again. The way things are shaping up even this is a large order. But there was also Spain. It may well be that the redemption of Czechoslovakia and of Poland will call for a military triumph on a grand scale over the conquerors who now hold them. It is not so with Spain. For the Spanish Republic lies physically, as well as in a moral sense, on the hands of those who betrayed it. It can be saved by humanitarian endeavor, not by battle. For on French soil are close to 300,000 refugees, the flower and sap of die Republic and the sole hope of the millions still in Spain under General Franco’s ruthless improvisations. Save them and the Spanish Republic is saved for the future, no matter what the political exigencies that maintain the generalissimo precariously in power for a time.

On French soil are close to 300,000 refugees, the flower and sap of die Republic and the sole hope of the millions still in Spain under General Franco’s ruthless improvisations.

It is a commonplace to say that during centuries there were two Spains in a state of permanent civil war, but for being a commonplace it is no less true. The dwindling minority of one of those Spains set upon the other and sought, with help from the most surprising sources, to annihilate it once and for all—to do with machine gun and bomb and foreign complicity what its predecessors with fire and stake had so signally failed to do long ago.

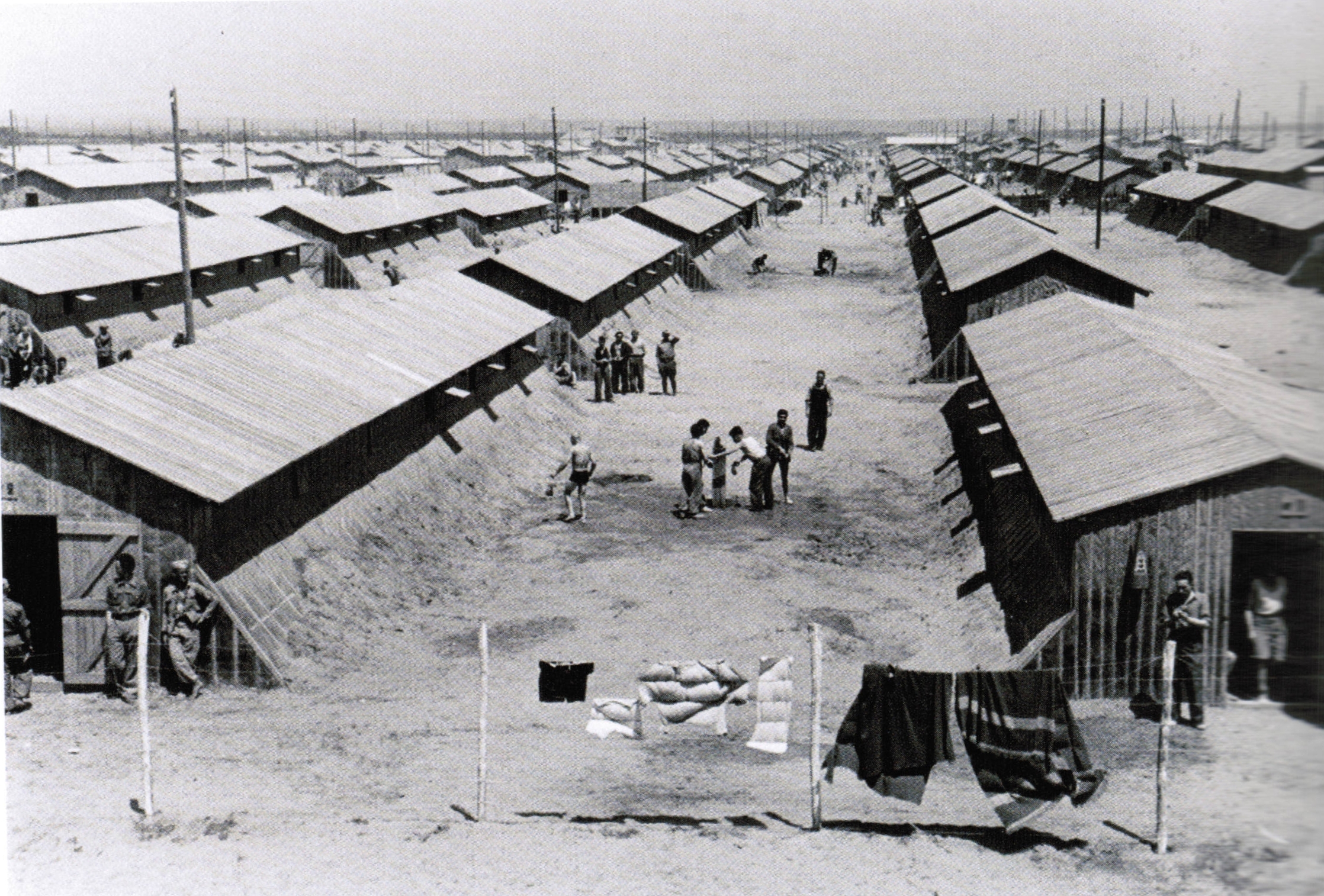

In concentration camps, in labor battalions in France, in exile in the New World are the victims—the other Spain that had proved itself so generous in the brief years of the Republic. They are more than a cross-section of the Republic; they are its core. Spain was not a large country for all her imperial heritage; and among her twenty-three millions, there were few who were, as Spaniards say, “prepared.” In the camps of France there are 2,063 school teachers; the Spanish Monarchy could have done wonders with that many school teachers had it approved of education. There are 2,440 printers—printers always seem to carry the spirit of 1789 in old societies. There are 2,809 electricians, 5,922 woodworkers, 17,000 builders and masons, 10,272 mechanics and 45,918 peasants—the enlightened workers who were the backbone of the second and—oh so moderate—Spanish Republic, who thought of progress not in terms of revolution but in terms of the development of their own capacities.

And there are dentists, pharmacists, nurses, opticians, architects, engineers, silk workers, topographers, agronomists, horticulturists, philologists, museum directors, aviation mechanics, viticulturists, distillers, tailors, hatmakers, musicians, lockmakers, blacksmiths, breeders of Arabian horses, psychiatrists, bullfight surgeons and, in modest proportions, army and navy officers. These were the riches and the hope of a people whom Havelock Ellis found to be the firmest-fibered race of all. This was the capital with which they sought, pathetically, to establish a pleasant nineteenth century republic in the thirties of this terrible century. In other countries such talents are taken for granted and sometimes ignored; in Spain “preparation” for even the humblest task was the promise of a rebirth of a people that was poor in everything but genius.

They were the Spain that wanted only to live and let live. But when this was not allowed them they fought, as no people have fought in our time. And because they fought against fascism they were called “Reds.” Strange that in the debris of the Republic, the debris that is also its hope, there should turn out to be only some 8 percent of communists and they, for the most part, men who had accepted a discipline that called for the maintenance of the political and social status quo.

Beaten, the Spanish Loyalist refugees came out of the war more of a nation than ever in their history.

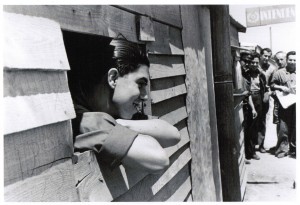

Beaten, the Spanish Loyalist refugees came out of the war more of a nation than ever in their history. They were the first victims of appeasement and now, with appeasement presumably dead, they are still its victims and, for the first time, their very survival is in doubt.

France, at war, finds them an even greater problem. The children are being sent back to Spain when Franco authorities, claiming the parents to be there, ask for them. And remember that Franco’s punitive “Law of Political Responsibilities” applies to everyone down to the age of fourteen. All adults are under fearful pressure to go back. Franco has promised immunity from his “purification” processes if they are not guilty of what he calls “crime.” The sincerity of such an amnesty would have to be checked on the spot by an international commission which would see to it that Franco’s definition of crime would not endanger the refugees. Since being a freemason or a democrat or a socialist is defined as crime in the statutes of Nationalist Spain, an amnesty might prove to be a very frail guarantee indeed. Of the 82,000 refugee militiamen; France has taken only 16,000 into industry and agriculture; 24,000 are in labor battalions; and 42,000 are still in concentration camps, where they have been for over eight months. One hundred thousand old men, women and children are also in camps. These are official French figures.

The point is not so much that these heroes of the first and, to date, only real war against fascism in Europe have sunk deeper into misery. It is that their hopes have been blighted.

The point is not so much that these heroes of the first and, to date, only real war against fascism in Europe have sunk deeper into misery. It is that their hopes have been blighted. Their own carefully devised plans to transplant their republic to the New World, there to keep it alive until the day when it should live again at home, have been cut short. Yesterday victims of appeasement, today they are hostages of appeasement; held thus to please General Franco who, if he so deigns, can one day become the glorious ally of the embattled democracies. There is little hope of a change in the French attitude. Help must come from some other countries which are not yet so desperately engaged in the struggle for democracy as to have to make such strategic capitulations in its name.

The Spain That Was

From below the Pyrenees comes the echo of the firing squads cleaning up the unfinished business encouraged by the Non-intervention Committee, and the day may well come, and soon, when General Franco will ask a price for joining in the crusade to save democracy.

All this is a far cry from the epic days of the defense of Madrid in 1936. The Spanish Republicans were very proud then. They were sure, then, that they were fending off the menace for all of Europe, and often in those early days you saw Spain pictured as a bull standing bloody but defiant, with a Hitler caught on one horn and a Mussolini on the other. That was in the days before the thing called Non-intervention was shown up to be the beginnings of the formula for surrender that in its later, more brutal, aspects came to be called Appeasement. There were still many illusions in Spain then.

Remember that Franco’s punitive “Law of Political Responsibilities” applies to everyone down to the age of fourteen.

They thought that the western world would come to understand. They knew that they hadn’t invented Spanish anarchism and Spanish Marxism; they were trying to leave the sick society that fostered them. They thought that the societies born of the French Revolution and the nineteenth century would remember that democracy and simple freedom had been thought worth fighting for long before it had reached its higher and fancier capitalist developments. And that once upon a time the defense of democracy by embattled farmers and other rabble was not deplored.

When the earlier illusions had gone and they saw not only Britain and France but the United States collaborating in a conspiracy to deny them arms in the name of Non-Intervention and Neutrality, while the generalissimo’s friends suffered from no such inhibitions, they held on to the idea that the true democrats of those three countries would understand that the conspiracy was not against Spain alone but all free men everywhere.

They may have dreamed, as was their right, of the day when appeasement would blow up in the faces of its authors. But when Munich came they knew it was the end for them. Nevertheless they fought on, in last ditches, having known the bombers, they knew that there was worse to fear.

They may have dreamed, as was their right, of the day when appeasement would blow up in the faces of its authors. But when Munich came they knew it was the end for them.

And some of them, the very wise, knew that with Munich the Soviet Union, which had helped from afar to hold the fort, was lost to a dream called collective security, or with Munich it was clear to everyone— who wasn’t led by a line—that the only collective action since sanctions were abandoned was collective security in reverse.

But when they went under they got some fine obituaries in the papers. On February 7, 1939, when Catalonia was falling, the New York Herald Tribune carried a moving editorial called “The Death of an Anachronism”:

All day Sunday and yesterday the wreck of the Spanish Republic was streaming northward through the passes of the Pyrenees the weary crowds of peasants and workpeople, the escaping officials, the hungry women, the lost and orphaned children, and the broken fragments of a valiant army in one vast tide of disorganization and defeat. One thinks of the terrible retreat of the Greek armies through Anatolia in 1922; one thinks of the Belgian armies pouring down the roads from Liege in 1914; one thinks of the wreck of the Grande Armée in the long twilight at Waterloo or of the great defeats and routs of history and one finds that none is quite a parallel for this mass fear and flight, this simultaneous dissolution of an army, a government, a people and an idea under the merciless blows of modern warfare . . . the republic is dead. The experiment which opened to such bright hopes in the spring of 1931 has been destroyed partly by its own ineptitudes and excesses, partly by the blind recalcitrance of the vested interests which it challenged, partly by the brute intervention of two alien dictators, but chiefly by the fact that it was born into a fiercely illiberal world which betrayed it at every step.

The responsibility had been still more clearly underlined by President Roosevelt who, a few weeks before in his message to Congress, admitted that our “neutrality” had favored the aggressor. “During those eight years from 1931,” he said, “many of our people clung to the hope that the innate decency of mankind would protect the unprepared who showed their innate trust in mankind. Today we are all wiser and sadder.” […]

The obituaries were premature. When the Republican Army came out of Catalonia it marched in formation, flags flying, and its chief, Negrín, a biologist and physician who had never asked more than to be left alone, was the last to cross. They were proud. True they had yielded to the Condor Legion and other phantom invaders whom the Non-Interventionists had never been able to detect. (The Condor Legion has since shown its substance in Poland.) They were proud because they knew that in thirty-three months of war their nation had been reborn, old Spain ground to bits, their return made inevitable.

What Americans Can Do

In France they were herded into concentration camps, quarantined for having fought too long and too well for democracy. Darker days were to come, as appeasement tightened. The Spanish Republic’s gold that might have kept them sheltered and fed was sent back to Franco. The generalissimo became a favorite with nice people. The United States came forward with a loan of $13,500,000 for the Spanish dictator and the U. S. State Department admits no knowledge of executions.

When Hitler entered Prague the Spanish Republicans felt certain that now would be an end to appeasement and they prepared to put the army of 150,000 that had come out of Spain at the service of France.

Appeasement, gold, loans all had failed to break the Axis. Then Stalin turned around and broke it and, breaking it, he left the British and French to fight Hitler and continue to appease Mussolini and Franco. Not in all their nightmares had the Spanish Republicans dreamed that the war bred by appeasement would find them still quarantined, disqualified to fight for the cause they had defended alone for so long, and barred from the hopes of victory, if victory there can be.

They were never abandoned altogether. In England they found such champions as the Duchess of Atholl, General Molesworth, the Dean of Canterbury, in Sweden Senator Branting, in France Cardinal Verdier who joined Academicians and others to help the child refugees.

In this country, for some reason, efforts by certain groups to label all Spanish refugee relief activity as something bordering on subversion have been for a time more successful than elsewhere. This factor, together with the shift of interest and the uncertainties of the outbreak of the war, resulted in a ruinous falling off of contributions. In England and France the war has brought down the contributions almost to zero. No funds can be sent from England for such purposes, and in France general mobilization has paralyzed most of the relief work.

The burden now rests largely on us.

All of the relief organizations are determined to go on. The Spanish Refugee Relief Campaign, of which Secretary [of the Interior Department of the US, Harold] Ickes is honorary chairman, has asked the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers) to supervise the distribution of its funds as an ultimate guarantee of its non-political character. The Spanish Confederated Societies have done likewise.[…]

What can be done in this country?

We can, before loaning more money to General Franco, suggest that he might prepare himself to take the veil of democracy by granting an amnesty to the vanquished and in the meantime cease the bloodlettings.

We can arrange to cooperate as a government with the Quakers and other relief organizations that are now ready to help settle Spanish refugees in the New World. […]

Why should we do this? Debt of conscience. And self-interest too. The democratic Spain, sole inspiration of sixty million Spanish speaking Americans at our borders cannot be allowed to die.

Suppose that in the sixteenth century the Spanish Armada had succeeded in its enterprise to bring fire to England. Then there would have been exiles or martyrs with such names as Spenser, Marlowe, Bacon, Dekker, Jonson Greene. A playwright from Stratford might have been among them. And had they been abandoned what would have been the loss to a liberal Anglo-Saxon civilization as yet unborn!

We know what would be the loss to the Spanish-speaking world today if the Spain that was never appeased is abandoned. It will die if abandoned.

This is a problem for us. Our share in Non-Intervention helped make them exiles. Now we have a chance, without going to war, to retrieve the error, to consolidate what still remains. Failure to do so and its consequences in Latin America would be another error that we may never have a chance to retrieve. It is up to us. The British and French have their hands tied. We have not, as yet.