Wounded Reporter Penned Letter on Back of Civil War Poster

The back of a Catalan poster held at the Bancroft Library in Berkeley holds a surprise: a 2,500-word, handwritten letter from Spain.

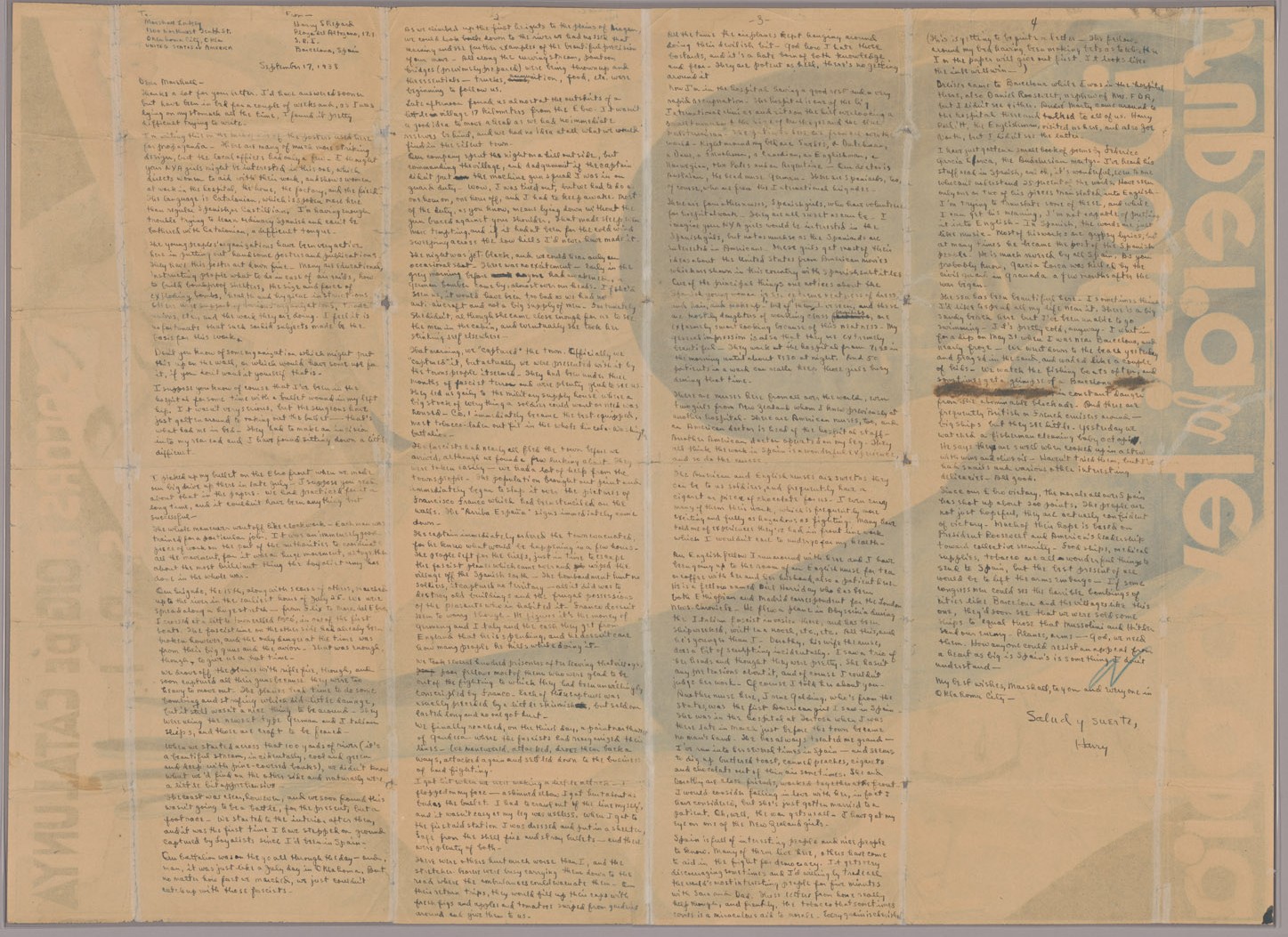

“¡Dona! supera la teva obra” poster with Harry C. Shepard Jr. letter on verso , Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Bay Area Post records, 1928-1995, BANC MSS 71/105 z. Courtesy of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Newspaper reporter Harry C. Shepard Jr., wrote a detailed letter on the reverse side of the poster ¡Dona! Supera la teva obra [Woman! Rise above your work], which champions the contributions of women to the Spanish Republic’s cause. He writes the letter to Marshall Lakey back home in Oklahoma City, recounting fervently his experiences and observations about the Spanish Civil War. Written from a hospital on September 17, 1938 where he is recovering from injuries after an offensive on the Ebro Front, Shepard provides insightful commentary about Republican troop movements, his stay at the hospital and the camaraderie of the soldiers and hospital staff. He also comments on the war in Spain, the Spanish people, and his stay in Barcelona.

The poster/letter are part of The Bancroft Library’s Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Bay Area Post Records, which includes a variety of materials, including correspondence, posters and broadsides, photographs, and numerous artifacts including pins, scarves and buttons. The records provide details of local, national and international engagement of the Veterans during the Spanish Civil War as well as the activities of the bay area post after the war, including its continued local and international political activism. The Bancroft Library is currently hosting an exhibition related to the 80th anniversary of the Spanish Civil War, which will be on view through April 2017.

A partial transcription of the letter follows. For the whole text, see The Volunteer’s online edition at albavolunteer.org. The letter was transcribed by Adrian Acu, PhD candidate in the English Department at the University of California, Berkeley.

Theresa Salazar is Curator of the the Bancroft Library Collection of Western Americana

To—Marshall Lakey

1300 Northwest Tenth St.

Oklahoma City, Okla S. R. I.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

From—Harry Shepard

Plaza del Altozano, 17.1

Barcelona, Spain

September 17, 1938

Dear Marshall—

Thanks a lot for your letter. I’d have answered sooner but have been in bed for a couple of weeks and, as I was lying on my stomach all the time, I found it pretty difficult trying to write.

I’m writing this on the back of one of the posters used here for propaganda. There are many of much more striking design, but the local officers had only a few. I thought your NYA girls might be interested in this one, which directs women to aid with their work, and shows women at work in the hospital, the home, the factory, and the field. The language is Catalonian, which is spoken more here than regular Spanish, or Castillian [sic]. I’m having enough trouble trying to learn ordinary Spanish and can’t be bothered with Catalonian, a difficult tongue.

The young people’s organizations have been very active here in putting out handsome posters and publications. They have this poster art down fine. Many are educational, instructing people what to do in case of air raids, how to build bombproof shelters, the size and force of exploding bombs, health and hygiene instructions. Others urge support of various organizations, trade unions, etc., and the work they are doing. I feel it is unfortunate that such sordid subjects made [sic] be the basis for this work.

The young people’s organizations have been very active here in putting out handsome posters and publications. They have this poster art down fine. Many are educational, instructing people what to do in case of air raids, how to build bombproof shelters, the size and force of exploding bombs, health and hygiene instructions. Others urge support of various organizations, trade unions, etc., and the work they are doing. I feel it is unfortunate that such sordid subjects made [sic] be the basis for this work.

Don’t you know of some organization which might put this up on the wall, or which would have some use for it, if you don’t want it yourself that is.

I suppose you know of course that I’ve been in the hospital for some time with a bullet wound in my left hip. It wasn’t very serious, but the surgeons have just gotten around to taking out the bullet—that’s what had me in bed. They had to make an incision into my rear end and I have found sitting down a little difficult.

I picked up my bullet on the Ebro front when we made our big drive up there in late July. I suppose you read about that in the papers. We had practiced for it a long time, and it couldn’t have been anything but successful.

The whole maneuver went off like clockwork. Each man was trained for a particular job. It was an immensely good piece of work on the part of the authorities to coordinate all the movement, for it was a huge movement, altogether about the most brilliant thing the Loyalist army has done in the whole war.

Our brigade, the 15th, along with scores of others, marched up to the river in the earliest hours of July 25. We were spread along a huge stretch—from Flix to Mora del [sic] Ebro. I crossed at a little town called Ascó, in one of the first boats. The fascist line on the other side had already been broken however, and the only danger at the time was from their big guns and the avion. That was enough, though, to give us a hot time.

We drove off the planes with rifle fire, though, and soon captured all their guns because they were too heavy to move out. The planes had time to do some bombing and strafing which did little damage, but it still wasn’t a nice thing to be around. They were using the newest type of German and Italian ships, and those are craft to be feared.

When we started across that 100 yards of river (it’s a beautiful stream, incidentally, cool and green and deep with pine-covered banks), we didn’t know what we’d find on the other side and naturally were a little bit apprehensive.

The coast was clear, however, and we soon found this wasn’t going to be a battle, for the present, but a footrace. We started to the interior after them, and it was the first time I have stepped on ground captured by Loyalists since I’d been in Spain.

Our battalion was on the go all through the day—and, man, it was just like a July day in Oklahoma. But no matter how fast we marched, we just couldn’t catch up with those fascists.

As we climbed up the first heights to the plains of Aragon, we could look back down to the river we had crossed that morning and see further examples of the beautiful precision of our move. All along the curving stream, pontoon bridges (previously prepared) were being thrown up and the essentials—trucks, ammunition, food, etc. were beginning to follow us.

Late afternoon found us almost at the outskirts of a little village 17 kilometers from the Ebro. It wasn’t a good idea to move ahead as we had no immediate reserves behind, and we had no idea at all what we would find in the silent town.

Our company spent the night on a hill outside, but commanding the village, and dadgummit if the captain didn’t put the machine gun squad I was in on guard duty. Wow, I was tired out, but we had to do a one hour on, one hour off, and I had to keep awake. Most of the duty, as you know, means lying down without the gun braced against your shoulder. That made sleep even more tempting, and if it hadn’t been for the cold wind sweeping across the low hills I’d never have made it.

The night was just black, and we could hear only an occasional shot. There was no excitement. Early in the grey morning before anyone had awakened, a German bomber came by, almost over our heads. If she’d seen us, it would have been too bad as we had no anti-aircraft and not a big supply of men. Fortunately she didn’t, although she came close enough for us to see the men in the cabin, and eventually she took her stinking self elsewhere.

That morning, we “captured” the town. Officially we “captured” it, but actually we were presented with it by the townspeople it seemed. They had been under three months of fascist terror and were plenty glad to see us. They led us gaily to the military supply house where a big stock of everything a soldier could want or need was housed. Co. 1 immediately became the best-equipped, most tobacco-laden outfit in the whole Lincoln-Washington battalion.

The fascists had nearly all fled the town before we arrived, although we found a few lurking about. They were taken easily—we had a lot of help from the townspeople. The population brought out paint and immediately began to slap it over the pictures of Francisco Franco which had been stenciled on the walls. The “Arriba España” signs immediately came down.

The captain immediately ordered the town evacuated, for he knew what would be happening in a few hours. The people left for the hills, just in time to escape the fascist planes which came over and wiped the village off the Spanish Earth. The bombardment hurt no soldiers, it captured no territory—all it did was to destroy old buildings and the frugal possessions of the peasants who inhabited it. Franco doesn’t seem to worry though. He figures it’s the money of Germany and Italy and the cash they get from England that he is spending, and he doesn’t care how many people he kills while doing it.

We took several hundred prisoners after leaving that village, poor fellows most of them who were glad to be out of the fighting to which they had been unwillingly conscripted by Franco. Each of these captures was usually preceded by a little skirmish, but seldom lasted long and no one got hurt.

We finally reached, on the third day, a point northwest of Gandesa—where the fascists had reorganized their lines. We maneuvered, attacked, drove them back a ways, attacked again and settled down to the business of hard fighting.

I got hit when we were making a little attack. I flopped on my face—a skinned elbow I got hurt about as bad as the bullet. I had to crawl out of the line myself, and it wasn’t easy as my leg was useless. When I got to the first aid station, I was dressed and put in a shelter, safe from the shell fire and stray bullets—and there were plenty of both.

There were others hurt much worse than I, and the stretcher bearers were busy carrying them down to the road where the ambulances could evacuate them. On their return trips, they would fill up their caps with fresh figs and apples and tomatoes swiped from gardens around and give them to us.

All the time the airplanes kept hanging around doing their devilish bit—God how I hate those bastards, and it’s a hate born of both knowledge and fear. They are potent as hell, there’s no getting around it

Now I’m in the hospital having a good rest and a very rapid recuperation. The hospital is one of the big International clinics and sits on the hill overlooking a small town about the size of Muskogee and the blue Mediterranean. The patients here are from all over the world. Right around my bed are Swedes, a Dutchman, a Dane, a Frenchman, a Canadian, an Englishman, a Norwegian, two Poles and an Argentine. Our doctor is Austrian, the head nurse German. There are Spaniards, too, of course, who are from the International brigades.

There are four other nurses, Spanish girls, who have volunteered for hospital work. They are all sweet as can be. I imagine your NYA girls would be interested in the Spanish girls, but not as much as the Spaniards are interested in the Americans. These girls get most of their ideas about the United States from American movies which are shown in the country with Spanish subtitles. One of the principal things one notices about the Spanish young woman is her extreme neatness of dress and hair, and makeup. All of them I’ve seen, and these are mostly daughters of working class families, are extremely smart looking because of this neatness. My general impression is also that they are extremely beautiful. They work at the hospital from 7:30 in the morning until about 8:30 at night. And 50 patients in a week can really keep those girls busy during that time.

There are nurses here from all over the world, even two girls from New Zealand whom I knew previously at another hospital. There are American nurses, too, and an American doctor is head of the hospital staff. Another American doctor operated on my leg. They all think the work in Spain is a wonderful experience, and so do the nurses.

The American and English nurses are sweet as they can be to us soldiers, and frequently have a cigaret [sic] or piece of chocolate for us. I even envy many of them their work, which is frequently more exciting and fully as hazardous as fighting. Many have told me of experiences they’ve had in front line work which I wouldn’t care to undergo for my health.

An English fellow I run around with here and I have been going up to the room of an English nurse for tea or coffee with her and her husband, also a patient here. He is a fellow named Bill Harriday who has been both Ethiopian and Madrid correspondent for the London New Chronicle. He flew a plane in Abyssinia during the Italian fascist invasion there, and has been shipwrecked, written a novel, etc., etc. All this, and he’s younger than I. Dorothy, his wife the nurse, does a bit of sculpting incidentally. I saw a trio of her heads and thought they were pretty. She hasn’t any pretensions about it, and of course I couldn’t judge her work. Of course I told her about you. Another nurse here, Irene Golding, who’s from the States, was the first American girl I saw in Spain. She was in the hospital at Tortosa when I was there late in March just before the town became no man’s land. She has always treated me grand—I’ve ran into her several times in Spain—and seems to dig up buttered toast, canned peaches, cigarets [sic] and chocolate out of thin air sometimes. She and Dorothy are close friends, worked together at the front. I would consider falling in love with her, in fact I have considered, but she’s just gotten married to a patient. Oh, well, the war gets us all. I have got my eye on one of the New Zealand girls.

Spain is full of interesting people and nice people to know. Many of them live here, others have come to aid in the fight for democracy. It gets very discouraging sometimes and I’d willingly trade all the world’s most interesting people for five minutes with Sara and Dad. Those letters from home really help though, and frankly, the tobacco that sometimes comes is a miraculous aid to morale. Every grain is cherished.

(This is getting to be quite a letter. The fellows around my bed having been making bets as to whether I or the paper will give out first. It looks like the ink will win.)

Dreiser came to Barcelona while I was in the hospital there, also Daniel Roosevelt, nephew of Mrs. FDR, but I didn’t see either. André Marty came around to the hospital there and talked to all of us. Harry Pollitt, the Englishman, visited us here, and also Joe North, but I didn’t see the latter.

I have just gotten a small book of poems by Federico Garcia Lorca, the Andalusian martyr. I’ve heard his stuff read in Spanish, and oh, it’s wonderful, even to one who can’t understand 25 percent of the words. Have seen only one or two of his pieces translated into English. I’m trying to translate some of these, and while I can get his meaning, I’m not capable of putting it into English. In Spanish, the words are just like music. Most of his works are gypsy lyrics, but at many times he became the poet of the Spanish people. He is much revered by all Spain. As you probably know, Garcia Lorca was killed by the civil guard in Granada a few months after the war began.

The sea has been beautiful here. I sometimes think Id’ like to spend all my life near it. There is a big sandy beach here but I’ve been unable to go swimming. It’s pretty cold, anyway. I went in for a dip on May 31 when I was near Barcelona, and nearly froze. We went down to the beach yesterday and played in the sand and waded like a couple of kids. We watch the fishing boats often, and sometimes get a glimpse of Barcelona in constant danger from the abominable blockade. And there are frequently British or French cruisers around—big ships but they see little. Yesterday we watched a fisherman cleaning baby octopi. He says they are swell when cooked up in a stew with wine and olive oil. Haven’t tried them, but I’ve had snails and various other interested delicacies. All good.

Since our Ebro victory, the moral all over Spain has shot up about 200 points. The people are not just hopeful, they are actually confident of victory. Much of their hope is based on President Roosevelt and America’s leadership towards collective security. Food ships, medical supplies, tobacco are all wonderful things to send to Spain, but the best present of all would be to lift the arms embargo. If some congressmen could see the horrible bombings of cities like Barcelona and the villages like this one, they’d soon see that we were sold some ships to equal those that Mussolini and Hitler send our enemy. Planes, arms—God, we need them. How can anyone resist an appeal from a heart as big as Spain is something I don’t understand.

My best wishes, Marshall, to you and everyone in Oklahoma City.

Salud y suerte,

Harry

Credit for images: “Dona! Supera la teva obra” with letter on reverse by Harry C. Shepard Jr. From the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, Bay Area Post Records, Banc MSS 71/105z, The Bancroft Library.