Guerrilla Violence across Borders: The Russian Revolution, the Spanish Civil War and the European Civil War

Historians have long recognized that Soviet military advisors had commanded troops in the Russian Civil War, suggesting that their experience shaped the way they viewed the Spanish situation. Did Soviet advisors introduce military strategies derived from the Russian Civil War—particularly, guerrilla tactics—into the Spanish war?

Was the Spanish Civil War a nexus through which violence moved across borders?—an epoch of military violence and ideological, cultural, political, social and economic conflict that began either in 1914, with the outbreak of the “Great War,” or with the Russian Revolutions of 1917, especially the Bolshevik Revolution, and ended in 1945, when fascism’s defeat brought a resolution of the conflicts that had wracked the European continent since 1914?

The concept of a European Civil War was first advanced by contemporaries who lived through it. Since then it has been adopted and refashioned by scholars and historical actors across the political spectrum, among them the political theorist Hannah Arendt, the controversial German historian Ernst Nolte, and the left-leaning scholar Enzo Traverso.[1] Its champions don’t agree on the chronological endpoints and causal mechanisms that generated violence across the European continent during this period. Yet they all oblige us to investigate how the civil wars and expressions of violence of this period became interlocked. An interesting case in point is the transnational odyssey of guerrilla tactics from the Russian Civil War, via Soviet advisors, to the Spanish Civil War — and then back to the Soviet Union as military tactics against the Nazi Wehrmacht, with the same advisors and Spanish Republican officers exiled in the USSR.

Guerrilla tactics traveled from the Russian Civil War, via Soviet advisors, to the Spanish Civil War — and then back to the Soviet Union as military tactics against the Nazi Wehrmacht.

It is certainly useful to think of the Russian Revolution and Spanish Civil Wars as interlocking events within a general European Civil War. But I am troubled by the way contemporary actors and scholars of the period have pointed to the Russian Revolution as a cause of subsequent violence. Particularly questionable are their claims that its influence consisted of ideas about violence and the role of the modern state in it. To be sure, ideas about violence are important to consider. But what were the processes by which specific historical figures transmitted what Nolte calls a “totalitarian germ” of the Russian Revolution across space and time? Moving beyond the murky claims about the causal effect across national borders of ideas about violence, in my work I focus on the human beings who carried the violent practices of the Russian Revolution—especially the Russian Civil War—across the European continent.

As for connections between the Russian Revolution and Spanish Civil War, it is well known that Soviet military advisors and other personnel were on the ground in Spain. Among them were Vladimir Efimovich Gorev (1900-1938), a key Soviet advisor in the Loyalists’ defense of Madrid in the late fall of 1936. Gorev has been credited by the American Louis Fischer with saving the city from Franco’s assault. General Gregory Stern was the Chief Military Advisor to the Spanish Republic. General Yakov Smushkevich played an integral role in defeating the Italian forces at the Battle of Guadalajara. Semën Krivoshein commanded tank forces of the Republican Army in the Battle of Madrid.

These Soviet military advisors differed in many respects, but with few exceptions, the common denominator was that they had helped the Soviets’ Red Army defeat their enemy, the White Armies, during the Russian Civil War. Gorev saw combat action in Russia and fought in another interwar conflict: the Chinese Civil War, which began in 1927. Smushkevich joined the Red Army and the Communist Party in 1918, and fought on the western front. He became commissar of a battalion and then of a regiment in the Russian Civil War. Like Smushkevich, Krivoshein enlisted in the Red Army in 1918, and fought in its First Cavalry Army.

Historians have long recognized that Soviet military advisors had commanded troops in the Russian Civil War and have suggested that this experience shaped the way they viewed the Spanish situation. Helen Graham has said that “Soviet personnel had a tendency to project the fears inherited from the Russian Civil War onto the Spanish situation, seeing saboteurs and internal enemies everywhere.”[2] Michael Alpert also asserts that “the Spanish Communist Party and the Soviet Russian advisers of the Republican Army inevitably thought in terms of their experience of the Russian Civil War of 1918-20.”[3] But did Soviet advisors introduce military strategies derived from the Russian Civil War into the Spanish war that otherwise would not have been there? And, if so, did it matter?

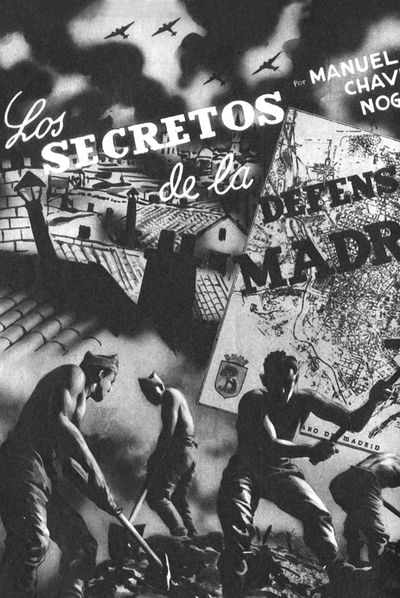

This is a huge issue, and what follows are some examples of my research in progress. First, let’s examine the Soviet advisors and their experience in the Russian Civil War in the Republic’s crucial defense of Madrid from October 1936 to January 1937. The defense of the capital went hand-in-hand with the creation of the Republican army, in large part the organizational work of Soviet advisors. The three most important of them were Vladimir Gorev, whom we have already discussed, as well as K.A. Meretskov, and B. M. Simonov. They provided the organizational blueprint for transforming, as Daniel Kowalsky puts it, the “Republic’s irregular militia forces and disorganized officer corps into a rigidly hierarchical institution modeled on the Red Army” that defeated the anti-Bolshevik forces in the Russian Civil War.”[4] All three joined the Red Army at the beginning of the Russian Civil War, and all played important military roles in it.

Not only were Soviet advisors, as veterans of the Russian Civil War, instrumental in transforming the disorganized Republican militias into a centralized, hierarchical fighting force, the Spanish Republican Army, or Ejército Popular. Not only, in that capacity, did they seek to reproduce in Spain their experience of creating a hierarchical and disciplined regular army out of the factory militias or “Red Guards” of the Russian Revolution. Not only did they bring to Spain the lessons they had learned from defending the Russian capital—Moscow—from the White Armies, lessons they would seek to apply in defending Madrid from Franco’s armies. What historians have often overlooked is that they brought to the Battle of Madrid their experience of commanding, participating in, or otherwise witnessing guerrilla actions against anti-Bolshevik Forces.

The Soviet military advisors in Spain had helped the Soviets’ Red Army defeat their enemy, the White Armies, during the Russian Civil War.

True, Spain had a homegrown tradition of guerrilla warfare, most notably on display against Napoleon’s invaders in 1807-1814, during the “Peninsular War.” And my attention to the Soviet role in importing guerrilla tactics into the Spanish Civil War will surprise those who recall that military historians have claimed that guerrilla warfare—if by that is meant guerrilla units or detachments—did not play a significant role in the Spanish conflict. It will surprise those who recall the blame that Spanish Communists and Spanish anarchists assigned for the fact that guerrilla warfare was not used as much as it should have been by the Republican side. In 1965, for example, the Spanish Communist Enrique Líster, one of the most storied combat officers of the Spanish Civil War and, in exile in the USSR, commander during the 1942 Battle of Stalingrad in World War II of a division of the Soviet Red Army, blamed the Republican Government for not organizing a “powerful guerrilla movement in Franco’s rear.” Spanish anarchists, such as the Anarcho-Marxist Abraham Guillén, who fought in the Spanish Civil War, criticized Soviet advisors for insisting on “frontal attack.”[5]

Yet Soviet advisors did play a crucial role in importing guerrilla tactics to Spain and in producing “guerrilla detachments.” Soviet advisors, certainly with Stalin’s knowledge, established six schools for training guerrillas in Spain.[6] Run by the Soviet Secret Police or the NKVD, these schools trained over 1,000 operatives for missions of short duration. The kinds of violent practices they were taught included, in the words of Alexander Orlov, head of the NKVD in Spain and a Russian Civil War veteran, “demolition work, high-grade marksmanship, elementary guerrilla tactics (raids and ambushes), map reading, living off the land, and long marches with loads up to 25 pounds.” “Saboteurs,” as he calls them, operated in “groups of seven or nine.” By night, they crossed into enemy territory with missions such as blowing up bridges across railway tracks, and, in turn, setting mines to blow up the “army emergency squads” when they came to the scene.[7] What comes to mind for readers of Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, is, of course the American International Brigade volunteer, Robert Jordan, who blew up a bridge.

Orlov himself stated that the guerrilla tactics applied in Spain had their origins in the Russian Civil War, or, more specifically, the Russo-Polish War. In his Handbook of Intelligence and Guerrilla Warfare, he wrote: “The experience gained by the Soviet guerilla troops in the Russo-Polish War became the cornerstone of the Soviet guerrilla science of the future. Sixteen years later, the former commander of the Soviet guerrilla troops in the Russo-Polish War was sent by the Russian Politburo to Spain, where he organized and directed guerrilla detachments which operated in the rear of Franco’s forces.”[8] (Orlov is referring to himself, of course!) Two American volunteers on the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War—Bill Aalto and Irving Goff—noted, in 1941, the Russian Civil War origins of guerrilla tactics they were taught in Soviet guerrilla schools in Spain: “In our guerrilla schools, lessons from the Red army’s experience were taught to us, verbally and through Spanish translations of Red army manuals. The mines and the trick apparatus we used in Spain were constructed from patterns given to us by our Soviet advisors.”[9]

- General Manue Tagüeña

- General Smushkevich

- General Líster

- Ilya Starinov

- Krivoshein

- Aleksander Orlov

Following the Spanish Civil War, when the Nazi Wehrmacht invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, many key Soviet advisors who had brought guerrilla tactics from the Russian Civil War were back in the USSR. But not all of them were, to be sure. Some, like Orlov, never returned to the USSR, because they feared becoming victims of Stalin’s purges. (Orlov fled to Canada in 1938, and eventually moved to the US, where he became an informer for the CIA.) Some had died in Spain. But many of the key figures—for example, Rodion Malinovsky, Marshal of the USSR and Defense Minister in the late 1950s and early 1960s, who fought in the Russian Civil War and the Spanish Civil War—were now tasked with defending the USSR from the Nazi invaders. Joining them were Spanish exiles, including Republican military officers such as Enrique Líster, Francisco Ciutat de Miguel, and Manuel Tagüeña Lacorte, who served in the Red Army even if they did not necessarily see combat action. In any case, Stalin drew upon their experience in Spain as he listened to his generals in mapping out military strategy against the Nazis.

The Soviet defense against the Nazi invasion involved key figures from the war in Spain—including Spanish exiles.

The USSR made use of, as Orlov put it, “the lessons of Spain” regarding guerrilla practices. Indeed, as Orlov described it—perhaps in effect crediting himself for having a key role in defeating the Wehrmacht, even in absentia: “[T]ens of thousands of ‘partisans’ (the Russian name for guerrillas), organized and led by the KGB guerrilla experts, harassed the German overextended lines of communications from Poland to Stalingrad, from Kiev to the Caucasus, and from Latvia to Leningrad, blowing up bridges and troop trains, mining roads, attacking marching columns, and plundering supplies and ammunition.”[10] The guerrilla strategies that the USSR employed against the overextended Nazi Wehrmacht were drawn straight from the Spanish Civil War, in which, as we have seen, the lessons of guerrilla warfare in the Russian Civil War had been applied.

A Soviet military officer who exemplifies these connections is Ilya Starinov (1900-2000), who joined the Red Army in 1918, fought in the Russian Civil War, served with the Republican Army in Spain, and, during World War II, led Soviet partisan (or guerrilla) units. In terms of the strategies that Red Army partisans applied against the Nazi Wehrmacht in World War II, the principle remained fundamentally the same as during the Spanish Civil War and the Russian Civil War: as Orlov put it, the basic strategy entailed “delivering a lightning blow and disengaging oneself from the enemy in order to get ready to strike the next blow at every turn”—and, as well, “not to enter into battle against superior forces and not to engage in a war of positions.”[11]

Just as Russia’s guerrilla tactics had to be adapted to Spanish circumstances, so, too did the Red Army (and KGB, which supervised the guerrilla units) have to adapt Spanish tactics to the “Great Patriotic War.” Soviet guerrilla bands were much larger than the Spanish guerrilla units: rather than 7-9, with the “influx” of peasants and urban residents, they reached several thousand. They were also able to wrest enemy weapons, such as “artillery, mortars and bazookas.” Such tactics enabled guerrillas to defeat “battalion-size units of the German army,” partly by sapping the seemingly formidable strength of the Wehrmacht by preventing “regular supplies in men and arms” from reaching Nazi troops deep in Soviet territory.[12]

During the European Civil War, the guerrilla warfare of the Russian Revolution had the effects it did—especially in Spain—because of the unpredictable movement of revolutionaries across borders. Important, too, was their ingenious adaptation of guerrilla tactics to the different military and revolutionary circumstances they faced.

NOTES

[1] Enzo Traverso, Fire and Blood: The European Civil War, 1914-1945 (New York: Verso, 2016), p. 26.

[2] Helen Graham, A Short History of the Spanish Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005) p. 66.

[3] Michael Alpert, The Republican Army in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. x

[4] Daniel Kowalsky, “Stalin and the Spanish Civil War,” Gutenberg e-book, section on “General Activities of the Soviet Advisors..” Accessed on 24 January 24, 2017, http://www.gutenberg-e.org/kod01/frames/fkod18.html.

[5] Walter Laqueurv, Guerrilla Warfare: A Historical and Critical Study (Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1976), p. 197.

[6] The first two, says Orlov, were located in Madrid and in Benimamet, close to Valencia. There were four other schools. The one in Barcelona had 600 men. Alexander Orlov, Handbook of Intelligence and Guerrilla Warfare (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1963), p. 172

[7]Ibid., pp. . 172-3.

[8] Ibid, p. 172.

[9]Boris Volodarsky, Stalin’s Agent: The Life and Death of Alexander Orlov (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 330. (The quote comes from an article that Aalto and Goff wrote in their experiences for” Soviet Russia Today.)

[10] Orlov, Handbook, p. 182.

[11] Ibid., p. 183.

[12] Ibid.

Glennys Young is Jon Bridgman Endowed Professor in History and Professor of International Studies at the University of Washington. She is working on two book projects: Refugee Worlds: The Spanish Civil War, Soviet Socialism, Franco’s Spain, and Memory Politics and Returned: From the USSR to Franco’s Spain during the Cold War.

One reason the lessons learned from the Spanish Civil War were not applied in greater measure in the USSR was that so many of the participants were purged by Stalin on their return. In “The Spanish Civil War” Hugh Thomas states (page 952)

“Among the Russians who came to Spain, Berzin, Stashevsky, Antnov-Osenko, Goriev, Gaikins, Rosenberg and Kkoltsov were all either executed or died in concentration camps. Berziln, Koltsov, and Antonov-Orseenko were subequently rehabilitated, much good that did them. Their deaths were regretted as a mistake, in passing, by Khruschev in his speech denouncing Stalin in February 1956 at the twentieth party congress of the communist party of the Soviet Union. The tank general, Pavoly, was shot by Stalin in 1941, when he had lost his army in the first weeks of the German advance. General Kulik was also shot in 1941, for foolishness over Red Army equipment. General Stern (Grigorovich) commanded the first Red Banner Army in 1938 against the Japanese at Chankon ferry and fought in Finland; he too was shot in 1941. Rychagov, a leading pilot in Spain, who fought in the Red banner Army, at Lake Khason, against the Japanese, was shot for failures against the Luftwaffe.

“Among the foreign communists who fought in Spain, the magnetic Kleber was executed in Russia before 1939, Gal and Copic soon afterwards. In the late 1940s, all communists from Eastern Europe who had fought in Spain came under the cloud of Stalin’s suspicion. The then Hungarian foreign secretary, Laszlo Rajk, commander of the Rakosi Battalion in the 13th International Brigade, ‘confessed”, at his trial in 1948, that he went to Spain on behalf of the police of Admiral Horthy, ‘with a double purpose,: to find out the names of those in the Rakosi Battalion…and…to bring about a reduction of the military efficiency of the Rakosi Battalion. I should add that I also carried on Trotskyist propaganda in the Rakosi Battalion’ After Rajak’s execution, many veterans of the Spanish Civil War in Eastern Europe were arrested,and some shot.”

Eastern European Communists assisted by Noel Field to leave French internment camps also came under suspicion after he himself was deemed to be opposed to Stalin.