Book Review: A Novel of Post-Civil War Spain

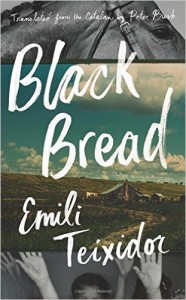

Emili Teixidor, Black Bread. Translated by Peter Bush. Canada: Biblioasis, 2016. 304 pp.

Through the voice of its child narrator, Andreu, Emili Teixidor’s novel Black Bread offers a penetrating look into the years of hunger in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish Civil War, roughly 1940-1950. As a kind of Bildungsroman, it escorts the reader through Andreu’s coming of age in a world of winners and losers that is haunted by the specter of the recent war, a reality that shapes how he grows up and winds up warping his pure and innocent spirit. Therein lies the critique that broadly steers Teixidor’s story: the young protagonist becomes a stand-in for a society that is forced to abandon its beliefs to survive in a country ruled by a dictatorial regime.

Through the voice of its child narrator, Andreu, Emili Teixidor’s novel Black Bread offers a penetrating look into the years of hunger in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish Civil War, roughly 1940-1950. As a kind of Bildungsroman, it escorts the reader through Andreu’s coming of age in a world of winners and losers that is haunted by the specter of the recent war, a reality that shapes how he grows up and winds up warping his pure and innocent spirit. Therein lies the critique that broadly steers Teixidor’s story: the young protagonist becomes a stand-in for a society that is forced to abandon its beliefs to survive in a country ruled by a dictatorial regime.

The black bread of novel’s title refers not only to the widespread and extreme poverty of post-war Spain, but also to a society that is dry, harsh, cruel, and soul-less, and that can lead astray even the most innocent of its members. The journey told in this novel is a double one, as Andreu’s life provides a pretext to reconstruct history through stories, giving voice to the past silence that articulates what she calls “the deceit of history.” Following in the footsteps of authors such as Ana María Matute (First Memory, 1959), Carmen María Gaite (Among Anti-macassars, 1957) and Juan Goytisolo (Fiestas, 1958), Teixidor uses the pure but critical point of view of a child to describe the consequences that the Civil War had on the defeated but, even more so, on the construction of social, cultural, and political discourses that many years later would define the transition and subsequent democracy. In other words, Teixidor attempts to show the perseverance in contemporary Spanish society of discourse rooted in the historical and social limitations imposed by Francisco Franco’s regime.

Two quotations that open the novel warn the reader about the inevitable and difficult connection between present and past, and history’s aspirations to tell the truth even if not always successful. As Andreu’s teacher, Mr. Madern tells us, “Considering that history is written by the winners, and the defeated don’t have the right even to a footnote in the big book of history….” What is claimed to be truth becomes something else. And here is where the reader becomes an unusual protagonist, charged as we are with recovering and making meaning of a narrative of silence about the past that has constituted the basis of Spanish democracy even today.

Teixidor uses the pure but critical point of view of a child to describe the consequences that the Civil War had on the defeated.

The linear narrative that covers several years in Andreu’s life contrasts sharply with the gaps, silence, and lack of information that characterize the world of adults that surrounds the protagonist. This illogical world is marked by the hypocrisy of the adults’ actions and the irrationality and corruption of the post-war period, and is what will pervert Andreu’s purity as he attempts to give meaning to the hushed stories that make up his everyday life. Here we see the connection between past and future through not just Andreu’s eyes but also through the constitution of words and, therefore, the novel we hold in our hands. Fiction inundates every aspect of daily life, not just the protagonist’s but ours as well. The imaginary world that attempts to give meaning to the puerile world of children unmasks the fiction of the reconstruction of history.

The author could be accused of committing the same mistake as those who wrote the official history. Like all authors do, Teixidor proceeds to create a narrative based on the selection of specific information—just as Andreu does—which together along with the rupture of a strictly chronological storyline, the simultaneous coexistence and absence of voices, and the Manichean division between good and bad, between children and adults, lays bare the manipulation of the narration and the gaps that are filled by fragile and not always dependable memory, whether information from newspapers or fairy tales. That is how Andreu’s grandmother explains reality to her grandchildren, and that is how we the readers receive it. Their stories begin with claims like, “Once upon a time there was, and you must believe that this is truly authentic…,” and like them, we believe we know the stories—all true—that they tell us. However, we only need one story, or even one new word, to change what we thought we knew so well.

By following the life of Andreu, Teixidor takes us on a voyage that makes us question what we know about the past and what we think we know about the present. In a moment in which organizations like the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (2000) and the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory in Catalonia (2005), and laws like the Law of Historical Memory (2007), are trying to make amends for the pact of silence that formed the basis of Spain’s transition to democracy, Andreu’s story reminds us not just about the problems that underlie the distortions of Francoist historiography and the official amnesia of the Transition, but also the problems that underlie the reconstruction of any illusory truth, wherever it may come from. And in this reconstruction we must acknowledge and accept, as our protagonist discovers, the monsters that dwell inside of us.

Olga Sendra Ferrer is an assistant professor of Spanish at Wesleyan University. She is currently writing her first book about the construction of Barcelona during the dictatorship.