Leo Eloesser: The Remarkable Story of a Medical Volunteer in Spain

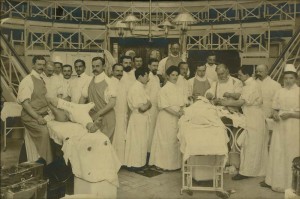

Among the American medical volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, Dr. Leo Eloesser, a thoracic surgeon affiliated with San Francisco General Hospital, organized a team of west coast doctors and nurses and brought his considerable experience of military medicine to Republican Spain. His extraordinary experience is chronicled in a recent volume written by a team of physicians, The History of the Surgical Service at San Francisco General Hospital (2007), including Dr. William Blaisdell, formerly with the University of California at Davis, from the following text is drawn.

Leo Eloesser, a remarkable man with global interests, was born in San Francisco in 1881, of German immigrant parents. The family was wealthy from manufacturing “Can’t Bust ‘Em” Overalls. His father was a pianist, and Eloesser and his three siblings were encouraged to study music. Upon graduation from Urban School in San Francisco, Eloesser was too young to be admitted to the University of California, so he studied music, which he wanted to pursue as a career. But a family friend, ophthalmologist Adolph Barkan, convinced him that he should study medicine. When Eloesser was admitted to UC, he failed most of his courses, and only with the intervention of his father was he given a chance to continue. At that point, he became a serious student and graduated in 1900. Dr. Barkan insisted that Eloesser should study medicine in Germany at the University of Heidelberg where Barkan knew the Surgery professor, Vincenz Czerny. Eloesser was enthralled with the German system of teaching because there was academic freedom, and no one cared whether the students attended classes or not. It was only necessary that the student pass a series of examinations. This allowed him freedom to pursue his interest in music in parallel.

On completing his studies and being awarded his degree in 1907, he became a voluntary assistant to Czerny. He spent six months in the pathology laboratory, gave anesthetics, and wrote a treatise on pancreatic diseases. He spent several years in Germany and, during this period, visited the Clinics of Mikulicz and Sauerbruch. Following this experience, he spent six months in England and worked in Sir Almoth Wright’s laboratory in St. Mary’s Hospital.

In January 1914, Eloesser told his father that he no longer needed monthly checks: “I have $500 in the bank and shall get on alone.”

In 1909, he returned to San Francisco. Because it was six months before he could qualify for licensure, he volunteered as an intern on the UC Service at San Francisco City and County Hospital, temporarily located at the Ingleside Racetrack while the new County Hospital was being designed and built. After a six-month internship, he rented an office and began private practice. He disclaimed any immediate success. “I spent more and more time at the hospital and less and less at the blank, patient-less office,” he said. “It was 10 years before I collected sufficient fees to pay the office rent.” His colleagues claimed that the reason he earned so little was a consequence of charging so few of the patients he treated, and charging so little to those he did. Finally, in January 1914, he told his father that he no longer needed monthly checks: “I have $500 in the bank and shall get on alone.” He stayed on the UC surgical staff, whose chief was Wallace Terry, while he set up his private practice. In 1912, Emmet Rixford, chief of the Stanford service, offered him a position and Terry advised him to take it because Terry considered the status of the UC Medical School tenuous. The UC Regents felt that it represented a costly drain on the rest of the University and were considering closing it.

During his initial period at Stanford, Eloesser did a great deal of experimental work on animals. He was also a courageous surgeon. Having been exposed to the German system, he was willing to undertake procedures that other surgeons would not. Some of these operations were bold and risky, but they were often successful.

Woe be it to the verbose student as he made rounds, and woe to the resident who tried to bluff his way through a history or diagnosis. A retort of “Bullshit” could be his lot.

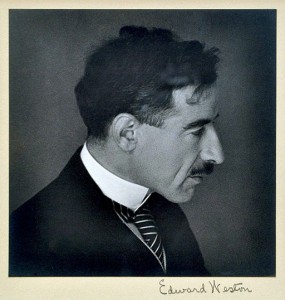

Eloesser was of slight build, barely over five feet tall. He had an intense look, a penetrating gaze that could skewer any mortal, and an extremely caustic tongue. He drove himself hard and expected others to follow his example. Woe be it to the verbose student as he made rounds, and woe to the resident who tried to bluff his way through a history or diagnosis. A retort of “Bullshit” could be his lot. Because of his size, Eloesser usually operated standing on a stool. Having been grounded in the fundamental branches of medicine and Germanic teaching, he knew pathology well and was able to examine his own microscopic sections, which he apparently did with great accuracy. He was an adequate, but not a brilliant, technician. His fame came primarily from his diagnostic acumen. As a teacher, Eloesser emphasized analysis over rote memorization, encouraging his students to use their mind critically and analytically to discard outworn, untrustworthy, and unsubstantiated opinions. He said, “I think that we all agree, in theory if not in practice, that trying to impart facts to students is futile, especially trying to impart them by word of mouth. Anyone in search of facts can find facts out by himself if he wants to.” Eloesser used the Socratic method to prod a student to make logical deductions. “Technique?” he said, “Ha! That is an easy thing to teach, a thing that should be taught, not to undergraduates of course, but to aspiring surgeons. Technique can be taught and it can be learned; learned by all the four avenues by which we learn any manual activity—by listening, watching, practicing, and doing. Some men’s hands will surpass their heads; for others, intellect will prevail over some clumsiness. It is our business as guides and teachers to recognize our pupils’ fortes; to do what we can to curb the dexterous avidity of the technically agile, and to stimulate the clumsy to practice their five finger exercises.” He was insistent that his students and trainees understand clearly that to know a patient’s symptoms, the abnormal findings on physical examination, the correct diagnosis, and even the treatment, was not enough. “Over and beyond this, they must try to unravel the puzzle—what is wrong anatomically; what was functioning improperly? What in essence is at the basis of the disordered state? If death should come, why?”

A brilliant scientific writer, Eloesser began publishing while he was still in training. He published a total of 92 articles—about half of them on chest surgery. He also wrote papers on amputations, bone grafts, aneurysms, peptic ulcer surgery, and anesthesia. His patients appreciated his care and loved him. His thorough evaluations assured them that no detail would be left to chance. He established compassionate, understanding, personal relationships with them. His patients could rest assured that if they were worrisomely ill or might profit from a visit, he could be counted on to be there at any hour of the day or night. As vouched for by Carl Mathewson, his junior associate at the County, “Leo was a workhorse. He had no concept of time, day or night.” By the 1930s, he also had a busy private practice, operating on private patients at French, St. Luke’s, Stanford, and St. Joseph’s Hospitals, and at the Dante Sanatorium. He then saw patients in his office until midnight, never turning anyone away who wanted to see him. He worked Monday through Saturday.

He never married, but he was never without women friends. In the 1930s he drove a large open convertible and was always accompanied by his dog, a German dachshund. His primary luxuries and relaxation were his boat and his viola. He owned a 28-foot ketch, “the Flirt,” and sailed regularly with a companion. He owned a flat on Leavenworth Street. Every Wednesday evening, a small group from the San Francisco Symphony would join him in his flat to play chamber music together. From time to time, this group was joined by distinguished visitors such as Pierre Monteux, Fritz Kreisler, and Yehudi Menuhin. He had a gift for languages—mastering German, Greek, Russian, French, Polish, Hungarian, Spanish, Italian, and Chinese—and once spent seven months teaching at the University of Tokyo Medical School in Japanese, having picked up the language from a dictionary and conversations with passengers on the ship going over.

Eloesser had a gift for languages and once spent seven months teaching at the University of Tokyo Medical School in Japanese, having picked up the language from a dictionary and conversations with passengers on the ship going over.

With the outbreak of World War I, he contacted his old chief, Professor Czerny, in Germany, and was put in charge of a surgical division of a large German hospital. There he published papers on the use of blood transfusion in war surgery and on the management of gas infections. When the United States’ entrance into the War was imminent, he returned to America. He tried to enter the U.S. Army, expecting his experience with casualty management would be welcomed but his German connections resulted in denial. However, he was asked to supervise a large orthopedic and rehabilitation ward at Letterman Army General Hospital in San Francisco. His ward was filled with amputees, and when the Army dragged its feet about setting up a prosthesis center, Eloesser went to Mare Island, borrowed machinery from the Navy, and set up an artificial limb factory. This factory then produced the highly successful “Letterman leg.” He also pioneered in the early fitting of these prostheses. Even while working at Letterman, Eloesser went to San Francisco County at night, where he saw many patients with empyema and other chest diseases, which were now attracting his interest.

At the end of the war, he returned to his position as assistant chief of Stanford’s County Surgical Service under Rixford and reopened his private office. The influenza epidemic of 1919 resulted in a flood of patients with lung abscess, bronchiectasis, and empyema, which further stimulated his interest in thoracic surgery. In 1926, he brought in, as his associate in private practice, his former house officer in surgery, William Lister “Lefty” Rogers. Eloesser’s clinical interests were general. He always had a major interest in fractures, which were then the province of the general surgeon. But as his private thoracic practice grew, so did his research interests in thoracic surgery. He became interested in tuberculosis and its treatment, devising the flap that bears his name, used for the chronic drainage of empyema. He was highly proficient in bronchoscopy, a technique he had learned in Germany, and he became interested in bronchial pathology and bronchial stenosis in particular.

In 1937, Eloesser went to Spain and served the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War for eight months. He took with him his viola, an ambulance, and a staff of physicians and nurses he had recruited.

In 1934, he visited Russia and installed a ward for thoracic surgery in the First University Surgery Clinic in Moscow. Three years later, after serving as President of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, he went to Spain and served the Loyalist side in the Spanish Civil War for eight months. He took with him his viola, an ambulance, and a staff of physicians and nurses he had recruited. He set up a military hospital and developed a blood bank service. While in Spain, he published a paper on the management of compound fractures. He regularly sent home requests for his El Toro Mexican cigarettes, Ghirardelli chocolates, and Hills Bros. Coffee, to all of which he was addicted. He had many friends among artists and musicians; these included the noted sculptor Ralph Stackpole and the Mexican muralist, Diego Rivera. Rivera’s wife, Frida Kahlo, painted the picture of him that today hangs in the lobby at San Francisco General Hospital. Eloesser returned from Spain in 1938 and resumed his duties at the City and County Hospital and his private practice.

Eloesser’s friends included Ralph Stackpole, Diego Rivera, and Frida Kahlo, who painted the picture of him that today hangs in the lobby at San Francisco General Hospital.

In 1945, he joined the United Nations Relief Organization, gave up his work in San Francisco, and went to China. As no one thought to acknowledge his retirement in the postwar ferment, he gave a retirement party for himself. His friend sculptor Ralph Stackpole had earlier immortalized Eloesser, peering through a microscope at the base of Stackpole’s giant statue for the American Stock Exchange, Man and His Inventions. Stackpole sculpted another statue, this time portraying Eloesser sigmoidoscoping a horse, which was the centerpiece of the dinner. This remained for many years in the hospital’s pathology laboratory before it disappeared. “It was a jolly goodbye party.”

Once in China, Eloesser became disgusted with the corrupt regime of Chiang Kai-shek and quietly made his way to Mao’s remote communist stronghold. He worked with the Communists for four years, living like a peasant and teaching hygiene, sanitation, and midwifery to the “barefoot doctors.” Serving at Bethune Medical School and adding Chinese to his repertoire of languages, he published, in Chinese, a manual for rural midwives titled Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Newborn. It was subsequently revised and published in Spanish, English, and Portuguese. The latest edition appeared in 1976.

In the McCarthy era, he felt persecuted; and in 1953, he retired to Tacambaro, Mexico, where he set up a small clinic to treat the disadvantaged in the area.

Eloesser returned from China in 1950, continued to work with UNICEF, and became interested in health care in third world countries. In San Francisco, at age 70, he met his companion for the rest of his life, Joyce Campbell. In the McCarthy anti-Communist era, he felt persecuted and unappreciated; and in 1953, he retired to the isolated small town of Tacambaro, Mexico. There he set up a small clinic to treat the disadvantaged in the area. His fees, which were modest, were given to the town clerk at the end of the year and were used to give Christmas presents to the prisoners in the County jail. Three months before his death, Eloesser gained Mexican citizenship and was awarded the Presidential Medal for his work with the poor of that country. He saw patients until he died of a massive coronary occlusion on October 4, 1976 at 95 years of age.

Wonderful article about a wonderful man. He was friends with our grandparents who

were part of the liberal German-Jewish community in SF although very much more radical.

Thank you so much!!

[…] Blaisdell, William. “Leo Eloesser: The Remarkable Story of a Medical Volunteer in Spain.” The Volunteer, 3 Dec. 2016, albavolunteer.org/2016/12/leo-eloesser-the-remarkable-story-of-a-medical-volunteer-in-spain/. […]

Our family is very proud of Leo Eloesser and very much appreciates this superb testimony to his accomplishments, courage and character.