Americans in Spain’s Civil War: A Convoluted Legacy

James D. Fernandez, New York University

Eighty years ago this week, in the Spanish North African enclave of Melilla, a group of right-wing generals staged a military coup, aimed at overthrowing Spain’s democratically elected government.

The July 1936 uprising unleashed what would come to be known – somewhat inaccurately – as the Spanish Civil War, a horrific conflagration that lasted almost three years.

The general consensus is that the war sent about a half-million Spaniards into exile, and another 500,000 to their deaths. Still today, more than 100,000 Spaniards lie in hundreds of unmarked mass graves strewn all over the Iberian peninsula.

Those mass graves still haunt contemporary Spain, and the question of how the Spanish Civil War ought to be commemorated is still far from buried, not only in Spain, but also in the U.S.

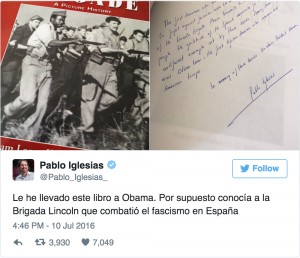

Just two weeks ago, when President Obama visited Spain, the gift he received from Pablo Iglesias, the leader of the upstart left-wing political party Podemos, generated controversy.

The present was a copy of the book “The Abraham Lincoln Brigade: A Picture History,” and in it, Iglesias penned a dedication to President Obama:

The present was a copy of the book “The Abraham Lincoln Brigade: A Picture History,” and in it, Iglesias penned a dedication to President Obama:

“The first Americans who came to Europe to fight against fascism were the men and women of the Lincoln Brigade. Please convey to the American people the gratitude felt by Spanish democrats for the antifascist example provided by these heroes.”

To understand the symbolism and the controversial nature of this gift, we must examine the convoluted legacy of that war whose 80th anniversary is commemorated this week.

International war

Pablo Iglesias’ inscription points to why the term “Civil War” is a misnomer when applied to Spain, 1936.

Though the Spanish war did pit Spaniard against Spaniard, the conflict quickly became international. Within days of the onset of the coup, Hitler and Mussolini intervened on the side of the insurgent generals. Before long, the Soviet Union would come to the aid of the Loyalists, also known as the Republican forces, who supported the government.

To the chagrin of Spain’s elected government, the U.K., France and the U.S., in full appeasement mode, decided to remain neutral. They even imposed – and enforced – an embargo on the sale of arms to the Republic.

Despite – or perhaps because of – that embargo, for the duration of the war, Spain would be on almost everybody’s mind in the U.S., whether they liked it or not.

Moviegoers, for example, eager to see newly released movies such as Charlie Chaplin’s “Modern Times” or Walt Disney’s “Snow White,” had to sit through newsreels depicting the new form of modern warfare being premiered in Spain. With melodramatic music swirling and swelling in the background, audiences would hear foreboding newsreel narrators exclaiming:

“hundreds of thousands of noncombatants suffer the indescribable horrors of a continuous nightmare of fear and destruction.”

The new medium of photojournalism – Life Magazine began circulation in 1936 – would bring fresh and horrifying images of the faraway conflict into the living rooms of average Americans.

Indeed, the war in Spain was felt with such immediacy in the U.S. that in an unprecedented display of international solidarity, some 2,800 American men and women risked life and limb to travel to Spain and join the International Brigades: the 35,000 volunteers from 50 nations who were recruited and organized by the Communist International to defend Spain’s Republic.

The first contingent of Americans arrived to Spain in January of 1937, and they called themselves the “Abraham Lincoln Battalion,” invoking the leader who had successfully presided over a Civil War in their own country.

New York University’s Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, Author provided

Ernest Hemingway’s portrait of Robert Jordan in “For Whom The Bell Tolls” would become the iconic image of an American volunteer in the Spanish Civil War. But if Hemingway’s protagonist was a solitary and rugged WASP from Montana, most of the nonfiction volunteers emerged from vast, politically active communities, which were decidedly urban, working-class and ethnic.

The closest thing to a rifle that most of the volunteers had ever handled before Spain was probably a picket sign. Unlike Hemingway’s outdoorsman, real-life volunteers were likely to have had more experience sleeping on tenement fire escapes than in field tents.

And for each individual who made the ultimate sacrifice of taking up arms in Spain, there were thousands of Loyalist sympathizers who stayed behind. They raised funds to send medical supplies to the besieged government. They urged the FDR government to “Lift the embargo Against Loyalist Spain.” They did their bit, as the popular slogan went, “to make Madrid the tomb of fascism.”

Anti-fascist war

The Republic, hamstrung by the embargo, and splintered by internal differences, eventually fell. Franco’s troops marched into Madrid in April of 1939. Exactly six months later, Hitler invaded Poland and, according to most standard accounts, World War II was officially underway.

The horrors of that war help explain why the memory of Spain was subsequently eclipsed and almost forgotten. But there were other forces at work that would contribute to the transformation of how Spain would be remembered.

The fact is that, at the time, for many contemporary observers, the war in Spain was of a piece with the war against Hitler.

For starters, the Lincoln volunteers frequently depicted themselves as soldiers attempting to stave off another world war. In November, 1937, for example, volunteer Hy Katz would write home to his mom:

“If we sit by and let them grow stronger by taking Spain, they will move on to France and will not stop there; and it won’t be long before they get to America. Realizing this, can I sit by and wait until the beasts get to my very door – until it is too late, and there is no one I can call on for help? And would I even deserve help from others when the trouble comes upon me, if I were to refuse help to those who need it today? If I permitted such a time to come – as a Jew and a progressive, I would be among the first to fall under the axe of the fascists; – all I could do then would be to curse myself and say, ‘Why didn’t I wake up when the alarm-clock rang?’”

Harris&Ewing, Library of Congress

In March of 1945, President Roosevelt himself, in a missive to a diplomat, would characterize the continuity he perceived between the Spanish war and WWII, between the Axis and Franco’s regime:

“Having been helped to power by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, and having patterned itself along totalitarian lines, the present regime in Spain is naturally the subject of distrust by a great many American citizens […] Most certainly we do not forget Spain’s official position with and assistance to our Axis enemies at a time when the fortunes of war were less favorable to us, nor can we disregard the activities, aims, organizations, and public utterances of the Falange [Spain’s Fascist party], both past and present.”

Even a publication like “Stars and Stripes,” a semi-official organ of the U.S. Armed Forces, would, in its European edition of July 1945, unhesitatingly affirm:

“Nine years ago last week, the first blow was struck in World War II. On July 17, 1936, in the picturesque garrison town of Melilla, in Spanish Morocco, a Spanish general and his Moroccan regiments proclaimed civil war against the infant, five-year-old Republic and its government…”

In 1945, the general contours of how the Spanish Civil War was likely to be remembered into the future were quite clear: as part and parcel of the long struggle against international fascism, perhaps even as the opening salvo of World War II.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the fifties…

Cold War

Between 1945 and 1955, Francisco Franco managed to refashion himself completely. No longer an ally of the Axis – in fact, he claimed that he had never been such a thing. Franco repackaged himself as a stalwart anti-communist, ruling over a strategic land mass at the corner of Africa and Europe. And it worked.

If, for FDR, Franco had been an illegitimate ruler, for Truman and Eisenhower, the generalissimo would become a crucial partner in the war between “freedom” and “communism.” Truman and Eisenhower helped end the Franco regime’s post-war diplomatic ostracism. In exchange, the U.S. got to build an archipelago of Cold War military bases on Spanish soil.

US National Archives

As Franco morphed from “Adolph’s Man in Madrid” to “Ike’s Man in Madrid,” and as the Spanish Civil War came to be viewed more and more through the retrospective lens of the Cold War, much history would get rewritten, on both sides of the Atlantic.

Franco actively destroyed or altered evidence of his dalliance with the Axis. And in the U.S., as historian Peter Carroll reminds us, it was precisely in anti-communist crusader Joseph McCarthy’s 1950s that George Orwell’s “Homage to Catalonia” became a fixture of the Cold War canon. Orwell’s book was a powerful indictment of the Communist Party’s ruthless behavior in the war, and it was used to cast a shadow over the experiences and motivations of the Lincoln Brigade.

Before long, in both Spain and the U.S., the Spanish Civil War would be talked about not so much as an early battle of the anti-fascist World War II, but rather as a chapter in the annals of communist mischief and perfidy.

The actions of American volunteers, rather than being seen as heroic and prescient, would become suspect. And that is why, even 80 years on, Iglesias’s gift to Obama could still seem laden with symbolism and wrapped in controversy.

James D. Fernandez, Professor of Spanish and Portuguese, Vice-President, Board of Governors, Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, New York University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.