The Man Bill Wheeler Could Not Forget

On May 20, 1938, Dave Lipton tells his parents that he is leaving for the Catskills to work as a waiter. Instead, he sails for Europe to join the Abraham Lincoln. Dave sends letter after letter home detailing his hopes and begging for forgiveness. He never receives a reply. Decades later, his niece Eunice Lipton stumbles upon clues that explain this silence. Her book A Distant Heartbeat, excerpted here, tells a tale of passion, heroism—and family betrayal.

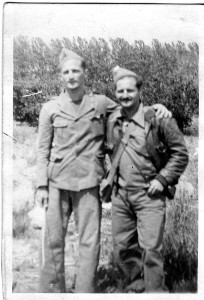

Each member of my family tried to imagine where Dave was shot. They were told that it was up near Gandesa in the mountains of northeastern Spain. Some stared into small black-and-white photographs. They scanned the crushed stones and spiky brush. Others thought they could hear dull bursts of old Russian guns or feel the heat and thirst, the fear and boredom. They tried everything. But all they got was silence. No one knew anything for sure. Only that one day in May 1938, Dave boarded a ship to France without telling his parents or brothers, that he disappeared into the Spanish Civil War.

The family knew he went to meetings and study groups, organized demonstrations, was earnest and committed. He came from a long line of European Communists. But Dave was a good son. He wouldn’t just leave like that. A good kid doesn’t do that. What got into him?

Dave was a good son. He wouldn’t just leave like that. A good kid doesn’t do that. What got into him?

There’s a photograph of Dave in a study group. He sits with five other boys and girls between seventeen and nineteen years old, the girls in sober skirts and starched blouses, the boys in shirts and ties and cardigans. Only Dave is in a suit and tie. They’ve probably been reading Marx. Maybe they’ll become intellectuals, teachers, labor organizers. One or two might dream big and fantasize about the Soviet Union.

Dave’s was a life that could have gone almost anywhere. He was a man with the inexhaustible energy that young immigrants carried to America.

Whenever Dave’s name was mentioned at home, his oldest brother, Phil shifted in his seat, my father’s eyes hardened, my mother’s eyes filled with tears. Phil said, “Of the three of us brothers, Dave is the only one that mattered. His life. His death. The rest of us are nobodies. Dave died for something. He was something.” My father, jittery and distracted, interrupted, “Listen, he was very sweet. I loved him dearly.” But he always added, “Ach, he died for nothing.”

Which was it? Who was this boy? The mild-mannered, determined youngster whose life was thick with bravery and hope? Or a sweet, naïve boy who incoherently threw his life away and permanently deprived his family of their deepest consolation, their youngest son?

I receive a package of Dave’s things from my brother. I sit down and undo the wrapping. The package includes letters, photographs, an announcement of a Lillian Hellman play, a newspaper fragment about minstrel shows with comments by Paul Robeson, a harmonica. There are also flyers about a memorial meeting held in Dave’s honor, and a tiny pin with a Liberty Bell. Across the top are the words, “Friend—Abraham Lincoln Brigade.”

I start reading the letters. The first one is to my grandparents and is dated July 10, 1938. It begins:

My dear Parents, I am sitting on a mountain among vineyards and olive trees covered with the blood of Spain. I am looking at the sunset and I weep, and weep and weep. I am crying with hot tears that are pouring out of my eyes and I don’t want to stop that flow of tears, because I think of you, my dear parents. The thought of the pain and anguish I cause you and the thought that you think of me while you are reading this letter. I cry because I could not kiss you before I left because I could not tell you where I was going and not explain why I was going and I could not tell you what Spain means to you and to the whole world. [F]orgive me, understand me and please don’t be angry.”

But then there is another letter dated two days later addressed to my father. “Dearest brother Lou!!!” it starts. “It was indeed a great and unexpected joy to receive a letter from you. Even though it has the taste of a trick to it. . . . In spite of the fact that your letter was cold and brutally hard, unbrotherly and so business like, sharp and condemning. . . .” Is this of a piece with my father’s, “He died for nothing”?

I decide to take the bus to Boston, where, at that time in 1996, there is an important archive of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade at Brandeis University. This archive is crammed into a corner of the Judaic Studies Department office. I introduce myself to Victor Berch, the librarian, and say that I’m doing a little research on my uncle who died in Spain, a member of the brigade. I give him some publicity about my last book and show him photographs of Dave. Then I gingerly lift up a tattered flyer for Dave’s memorial in the Bronx, on January 18, 1939. Mr. Berch is not impressed. He points to the three speakers listed on the flyer, David McKelvy White, Yale Stuart, and Bill Wheeler. “Dead. Dead. Dead,” he says, pronouncing the words with some derision, as if it were my fault. He tells me that if I’m interested, there’s a videotaped interview of Wheeler made in 1986, as well as indexes and photographs I can consult.

“No,” Abe shakes his head. “Wheeler’s not dead.”

I leave Brandeis disheartened. Nonetheless, back in New York, I decide to visit the office of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB) on East Eleventh Street. I have already spoken to Abe Smorodin, one of the Vets who works there. I also heard about him in the Wheeler video. Smorodin had been among the swiftest and most courageous runners in Spain. He’s eighty-one, with one eye nearly blind since birth and another the color of black onyx, which fixes you with unwavering attention. I remove my photos and flyers from my briefcase and, to show him how in the know I am, I point to the three names on the flyer and repeat Berch’s hortatory: “Dead. Dead. Dead.”

“No,” Abe shakes his head. “Wheeler’s not dead.”

“He’s not? Where is he?” I’m shouting.

“Where the hell were you twenty years ago? There were a lot more of us around then, and we had better memories.”

“I’ll get you the address and phone number.” In a few minutes, he returns, saying, “Okay, here’s the information about Bill.” When I’m almost out the door, he adds, “And where the hell were you twenty years ago? There were a lot more of us around then, and we had better memories.”

Just because Wheeler spoke at Dave’s memorial doesn’t mean he knew him, I say to myself on my way home. He was probably just doing his duty, the job of attending memorial services divided up among Veterans. Still, there was that proximity, Wheeler’s name on the flyer next to Dave’s. It’s why I watched the video at Brandeis in the first place, why I scrutinized his face, his hands, the way he moved in his chair, his voice, his silences. I write to him:

Dear Mr. Wheeler,

I am working on a book about my uncle Dave Lipton who died in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. He was a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and was in the First Platoon, Company 3. He died on August 20, 1938 near Gandesa on the Sierra Pandols.

I am trying to locate—at this late date alas—people who may remember him, however slightly. I’m enclosing a picture of Dave with his comrades.

I hope it’s all right if I call you in a week or so and see if you can help me.

I look forward to speaking to you soon.

Sincerely yours . . .

A week later he faxes me: “I do remember your uncle Dave Lipton and now thanks to you, he has a name that time and a flagging memory have erased. Dave’s death more than any of the too many others I have witnessed has haunted me to this day.” I can’t believe my eyes, this unexpected arrival of an outsider’s knowledge of the central enigma of my family.

“Just as I yelled to him to get down, he was struck by a sniper’s bullet.”

“Dave and I first met aboard the ship that was carrying several new volunteers and seven of us who had been sent home and were returning for the second time…. Dave and I were both assigned to the 3rd company of the Lincoln Washington battalion. After a short period of training, about the end of June or beginning of July 1938, we assembled on the banks of the Ebro River in preparation to launch the Ebro offensive. We were at rest the evening before the crossing. Dave handed me a letter written in Yiddish asking me to mail it to his brother (as I recall) if anything should happen to him. I remember telling him, ‘You will make it O.K. Just keep your head and fanny down.’ The next morning he asked for the letter back and tore it to bits. That morning we crossed the Ebro and proceeded on a three day march ….we moved on to Hill 666…. One of our squads was short handed and requested a replacement. Dave’s sergeant sent him to reinforce the squad. While with that squad Dave was sent with a detail to the bottom of the hill for grenades…. shortly after this I was checking our position at the front when Dave walked over towards me asking if he could return to his regular squad. Just as I yelled to him to get down, he was struck by a sniper’s bullet sinking slowly to the ground in front of me. In war one becomes inured to death but Dave’s has haunted me ever since. He was young, he was brave. . . .”

I want to tell my father: Dad, there’s a witness. I’ve found Bill Wheeler. I found Dave’s friend. He had a friend before he died. He wasn’t alone. And Dad, Dave was brave. Wheeler says so. But then the torn up letter comes back to me. Why did he do that? Had he said something he was uncertain about? Something angry? Or were they just words of love and good-bye that he thought might undermine his resolve, bring him bad luck? And more importantly why have I never found letters to Dave? Why only the letters he wrote? Surely his friends and family wrote to him.

Wheeler says that he’s haunted by the boy and has been all his life. I order a copy of the video from Brandeis, and this time I watch it to the end. The last question the interviewer asks is “What stays with you the most from your experience in Spain, Bill?” Wheeler looks pensively into the camera and says again, “this boy came walking over slow and measured and he said, Bill, can I go back to my squad? He was standing there. And just as I was about to yell at him to get down, a sniper got him. He stood there yelling, No, no, no, and fell right there at my feet.”

I pick up the phone and call Bill Wheeler in Athens, Georgia.

I introduce myself. We are polite. We fall silent.

“Bill,” I call him, “I can’t believe I’ve found you. After all these years.”

“It’s odd, isn’t it?” he says.

“Bill, I . . .” I’m crying. I can hear that he is too. We sit in our separate worlds, lonely for our pasts, which are so tenuously connected yet somehow kindred. We both lived the death of my uncle but also the glory of a past long gone for one, never experienced by the other, yet cherished.

“Bill, I’d like to come talk with you.”

“Please,” he says.

And so I come to meet Bill Wheeler, who it turns out also shared some beers on shipboard with Dave, spent a night in Paris with him, heard shy stories from the boy about his romantic and political longings. A sweet friendship that once told untied my uncle from the narrative grip of my family and offered up an uncommonly gentle, curious and brave man who far from dying for nothing died for everything.

Addendum

Before Dave left for Spain he was active in the Young Communist League in the Bronx and was close to a young woman whom I will call Evelyn. When I track her down in the late 1990s she gasps over the phone, “Dave’s been on my mind all these years. I can’t believe you’ve found me. You’ve made my life worthwhile.” Then she confides, “I never knew a man like him, so soft and kind and good.”

When I meet Evelyn and we’re sitting together on her screened-in porch, she tells me of being “early for a class and hiding behind a book. I had things to say when necessary,” she said. “But I was shy. Dave would come over and talk to me. It meant a lot. And it wasn’t easy in those situations. The men were always vying for the limelight. But not him. He wasn’t a flashy, talky, aggressive leadership type. He was dependable, constant. He never raised his voice. He listened. . . . The others could be ruthless.”

I have found over the years that there are men with whom women feel comfortable, and those women are grateful. According to my mother and Evelyn Dave was such a man, gentle, kind, patient. This was the man Bill Wheeler met and never forgot. The ranks of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade were filled with men just like that.

wonderful story of one woman’s quest to learn of her never seen uncle