Spain and Syria: Beyond Superficial Comparisons

There are numerous comparisons that can be made between the conflict in Syria and the Spanish Civil War. Both conflicts feature a ruthless dictator, appalling loss of life, war crimes and the massive displacement of tens of thousands of refugees. However, such superficial comparisons apply to many other conflicts. Merely in terms of the domestic situation in both countries, there is a huge difference. Both wars saw a fragmentary coalition locked in combat with a better armed enemy. In Spain, a tightly organized military coup was launched against the legally elected government of the Second Republic and it was this Government the coalition was defending. The situation in Syria, is the exact opposite given that there, the rebels are the disparate and fragile coalition that opposes the authoritarian regime of Dr Bashar al-Assad which uses the apparatus of the state against them.

There are numerous comparisons that can be made between the conflict in Syria and the Spanish Civil War. Both conflicts feature a ruthless dictator, appalling loss of life, war crimes and the massive displacement of tens of thousands of refugees. However, such superficial comparisons apply to many other conflicts. Merely in terms of the domestic situation in both countries, there is a huge difference. Both wars saw a fragmentary coalition locked in combat with a better armed enemy. In Spain, a tightly organized military coup was launched against the legally elected government of the Second Republic and it was this Government the coalition was defending. The situation in Syria, is the exact opposite given that there, the rebels are the disparate and fragile coalition that opposes the authoritarian regime of Dr Bashar al-Assad which uses the apparatus of the state against them.

Furthermore, both countries have experienced the damaging interventions of foreign powers intent on playing wider political and diplomatic games and providing military support without directly engaging in the conflict. In Spain, Germany and Italy were directly involved in supporting Franco’s uprising while the western powers’ policy of supposed ‘non-intervention’ ensured the defeat of the Republic. And now in Syria, shifting international allegiances and diplomatic hostilities between the many countries engaged in the conflict, along with the hesitant and indecisive role played by decision-makers in Britain, France and the United States understandably concerned only with their own foreign policy goals, has further inflamed an already volatile situation.

However, even this comparison is complicated because of the differences in the global issues being played out in the two civil wars and their wider consequences. Oil – and the ‘war on terror’ with which it is closely associated in western political rhetoric – imbues the conflict in the Middle East with its most obvious global significance. The Spanish Civil war proved to be the first battle in wider European Civil War that culminated in World War II.

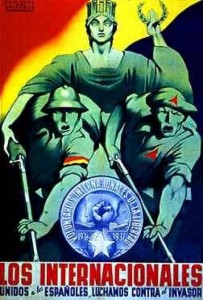

The area in which the most pertinent comparisons can be made is the role of international volunteers in both conflicts, particularly in terms of the parent governments of the volunteers themselves. In various ways, the governments whose citizens went to Spain and now to Syria tried to control the flow and, both then and now, made threats about sanctions ranging from withdrawal of citizenship to the imprisonment of volunteers. Approximately 2500 men and women from Britain and more than three times that number from France volunteered to defend the democratic regime in Spain which, at the time, was a country of which most of them knew very little. That in itself is a significant difference. In a period of infinitely greater sophisticated communications, technology and travel facilities, far fewer volunteers have gone to the Middle East. It is estimated that around seven hundred French, four hundred British and around one hundred Spanish citizens have gone to fight in Syria.

It is impossible to generalise with any certainty about what has motivated the bulk of the jihadist volunteers from Western countries. It is therefore extremely difficult to compare the motivations of Spanish, French and British Islamic jihadists fighting in Syria with the ideologically motivated men and women who served in the International Brigades in Spain. They went to resisting the relentless spread of fascism across Europe and served in a regular army. They did not attack unarmed civilians. However, in Syrian as in Spain, some were initially motivated by humanitarian considerations. It is also the case that both conflicts have seen some individuals driven by a desire for adventure. Other similarities can be found with regard to the far fewer volunteers who fought for Franco. Many fighting in Syria are driven by a sense of outrage at the causes and consequences of western intervention in Iraq and Afghanistan. Others, like the volunteers for Franco, are motivated by sectarian religious considerations. Others still are driven by the linked issues of inter-Muslim Sunni versus Shia conflict.

Inevitably, therefore, the bulk of foreign volunteers are from other Arab countries or, if from the western countries, from Muslim immigrant families. In the Spanish war, in so far as there was uniformity of the volunteers, it was ideological rather than ethnic. Those volunteering for Franco were ostensibly religious and anti-communist. Estimates vary wildly, although it seems clear that in Syria more foreign Sunnis are fighting with the rebels than there are foreign Shias fighting in defence of the Assad regime.

Franco made an absurd claim that there were no foreigners among his troops. Despite being described as volunteers, all of the 20,000 Germans, and many of the 80,000 Italians and 8,000 Portuguese who fought with the rebels were properly trained regular soldiers on full pay whose service in Spain counted in their military record back home. However, there were between 1,000 and 1,500 genuine volunteers on the Francoist side. There were White Russians who had fought against the Bolsheviks in their own civil war. The Jean d’Arc battalion consisted of about three hundred French from the Croix de Feu and other extreme rightist organizations. There was also a motley crew of Poles, Belgians, Rumanians and other extreme rightists, Catholics, fascists and anti-semites from all over Europe. The largest contingent of foreign volunteers for Franco was made up of were the seven hundred Catholic Blue Shirts of the Irish battalion under General Eoin O’Duffy who believed that they were taking part in a religious crusade.

In Spain, volunteers from the world over flocked to fight for the Republic. Some were unemployed, others were adventurers, but the majority had a clear idea of why they had come: to fight fascism. For the victims of the fascist regimes of Mussolini and Hitler, it was a chance to fight back against an enemy whose bestiality they knew only too well. Forced out of their own countries, they had nothing to lose but their exile and were fighting to go back to their homes. One of the battalions which saw its first action in Madrid, and which was to suffer enormous casualties, was the Thaelmann, consisting mainly of German, and some British, Communists. Esmond Romilly was a British member of the Thaelmann Battalion. He later wrote of his comrades-in-arms:

‘For them, indeed, there could be no surrender, no return; they were fighting for their cause and they were fighting as well for a home to live in. I remembered what I had heard from them of the exile’s life, scraping an existence in Antwerp or Toulouse, pursued by immigration laws, pursued relentlessly – even in England – by the Nazi Secret Police. And they had staked everything on this war’. Indeed, when the Republic finally fell in 1939, many German, as well as Italian, anti-fascists were still fighting in Spain. They ended up in French camps, and many fell into the hands of the SS and died in the gas chambers. Again, we find here a significant difference in terms of what most of the foreign jihadists can expect when they return to France and Britain. For British, French and American volunteers, the need to fight in Spain was somewhat different. They made more of a conscious choice. The hazardous journey to Spain was undertaken out of the awful presentiment of what defeat for the Spanish Republic might mean for the rest of the world. They believed that, by combating fascism in Spain, they would be fighting against the threat of fascism in their own countries. Recruitment was largely organised by the Communist Party. Not all volunteers were Communists, although many were. Political affiliation did not affect the idealism and heroism of those who sacrificed their comfort, their security and often their lives in the anti-fascist struggle.

Perhaps the most obvious area of comparison is the reception awaiting surviving volunteers as they attempt to return to their home. As is increasingly the case with jihadists returning to western countries, the volunteers of the International Brigades faced suspicion and outright hostility from the British Foreign Office and the security services. Secret internal security instructions showed that a principal fear was that the returnees would want to join the British armed forces in order to continue their fight against fascism: ‘While some of these men may have returned to this country disillusioned, there is no doubt that the majority of them have returned strongly imbued with revolutionary sentiments.’ Other western governments were concerned that the volunteers would want to make Communist propaganda within the working class. The equivalent today for western governments is the worry about radicalised Muslim volunteers returning to radicalise Muslim youth at home.

The British government made major efforts to prevent veterans joining the armed forces in the Second World War although many did so and served with distinction. The same happened in the United States where the veterans were deemed to be ‘premature antifascists’. Many others later described experiencing discrimination in their workplaces for many years after. How many of the British and French Muslims fighting in Syria will ever be able to return to their homes is unclear. What seems extremely likely – and the imprisonment of Flavien Moureau confirms – is that those who do will be viewed by the British and French security services with at least the same and probably greater suspicion than were the volunteers of the International Brigades. After all, from September 1939 onwards, despite the class prejudices of the ruling class and senior military officers, the fight of the volunteers in Spain had become was the fight of the majority of British and French citizens. There will be no equivalent whatever the result of the war in Syria.

Thanks for the thoughtful commentary, Paul.

I found the comparison with the O’Duffy (and North American catholic) volunteers to be most apt. But fighting for a religious reason is still an “ideological motive”. People always fight for one ideology or other. I suspect that the motivations of ISIL volunteers from the West also has a political strategy behind it because I don’t feel that ISIL is particularly “religious” other than to use Islam as an excuse to take power. That is quite similar to Franco’s motivations because he certainly would not be considered a “religious” man now.

We shouldn’t forget that the SCW volunteers knew that they would face difficulties on returning since they often changed their names in Spain and later again at home, and all saw the “Not Valid for Travel to Spain” stamp in their passports. I am sure that many expected the reaction of the right when they returned home. The French treated the European brigadistas much more harshly, interning them for years at Gurs and the other camps and then turning them over to the Nazis to die at Malthusen and Auschwitz. (I was intrigued reading how large a fraction of the Spanish internees subsequently led the Maquis and Remi Skoutelsky’s book is an excellent review of the French involvement in “De Gaulle’s” army. Pardon if you cover this also in your most recent book which, I confess, I have not read.)

Any young person going to Syria to fight for ISIL should not expect that their return home will be any more welcoming than the Brigades received. Their decision-making process is as complicated personally for them as it was for the Brigades.

Dr. Preston,

I’d be interested to hera more of your thoughts on the anarchist “Democratic Confederalism” in the Rojava area of Kurdish-dominated northern Syria. Volunteers from the US, Australia and elsewhere are fighting alongside the YPG and YPJ and are having success in their battle against ISIS. A recent Village Voice article told the story of two American “Anarcho-communists” who went to Syria to fight ISIS, inspired by the efforts of the International Brigades 80 years earlier.

I have a lot of respect for Paul Preston. One of my friends, Leandro Moura, was a student of his at the London School of Economics. When I was at the LSE, I took the European Civil War class that he designed. I even rescued a copy of his biography of Franco that had fallen on to the railway track at the local station once. While I spent my teenage years reading a number of the anarchist and Trotskyist accounts of the Spanish revolution, I defer to Professor Preston’s much greater knowledge of Spain.

However, I feel the reverse is the case with respect to Syria. Having spent the last 51 months following events in Syria on a daily basis, but reporting and analysing the experiences of Syrian revolutionaries, I think he falls for many of the false generalisations our media has made about Syria; that the opposition are undifferentiated jihadis, that the extreme jihadis of ISIS are the opposition to Assad, that the Assad régimne is secular, that the West has been supporting the opposition.

“It is impossible to generalise with any certainty about what has motivated the bulk of the jihadist volunteers from Western countries.”

Certainly without asking them. Let’s give that a go.

“It was the pictures everywhere, on Sky News that he was watching, of people being raped and children being killed, which inspired him to go,” said Mrs Sarwar. “These images were everywhere. He went to Syria to help the Free Syrian Army.”

[http://notris.blogspot.co.uk/2014/12/police-betrayed-me-says-mother-of.html]

‘Many British Muslims share Hussain’s view that Syria’s jihad has blurred lines. Al-Qaeda linked groups are involved – but many people believe that the conflict is closer in character to the civil war in Bosnia. Some compare it to the Spanish Civil War in which international brigades of young men fought against General Franco.

“My brother was not a terrorist. My brother was a hero,” says Hafeez Majeed.

“If I could put it like this, if my brother had been a British soldier and there were British people in that prison, I know he would have been awarded the posthumous Victoria Cross.”‘

[http://notris.blogspot.co.uk/2014/03/the-man-from-martyrs-avenue-who-became.html]

“Parliament decided not to intervene, but it’s within this context that the two British men I’ve spoken to took it upon themselves to do, they say, what the government couldn’t, to defend the people of Syria. Now they’re back in the UK and living in fear of arrest.”

[http://notris.blogspot.co.uk/2015/01/we-were-defending-british-values-say.html]

‘Similar motivations led Ibrahim to travel to Syria. He recalls being “horrified by the attacks carried out by the regime” when he saw images of dead civilians and crying children broadcast on the news, and claims that it was his duty to go there to help, because “if you had the means to go and help the oppressed, then you should”.’

[http://notris.blogspot.co.uk/2015/06/british-men-who-fought-bashar-al-assads.html]

“They did not attack unarmed civilians.”

I can only find one account of British volunteers participating in atrocities, but fighting for ISIS against Free Syrians.

‘In a letter to The Times, Brig-Gen Abdulellah al-Basheer of the Free Syrian Army asks for help in curbing the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

He claims the group attacks opposition forces, not the Assad regime.

“We the Syrian people now experience beheadings, crucifixions, beatings, murders, outdated methods of treating women, an obsolete approach to governing society. Many who participate in these activities are British. The UK and US governments must support us to defeat terrorism in Syria and prevent it from being exported to Europe and the US.”‘

[http://notris.blogspot.co.uk/2014/05/syria-crisis-britons-accused-of-brutal.html]

Prreston’s expertise on Spain, does not imply accurate comparisons without corresponding expertise on Syria. Without considering the role of “volunteers”, even without this, his article is strange. Spain before Franco was only ever a semi democracy, governed by a land owning and business elite backed by the Catholic Church. Preston knows better than anyone the lack of control the new Popular Front Government of 1936 had over the state. The so called “rebels” controlled the vast bulk of the effective parts of the Spanish Army, with the unreserved support of Fascist Italy and Germany. Franco while being termed a “rebel”, actually controlled the military apparatus of the state as Assad does. Franco was actually protecting the interests of a very well established Spanish elite, just as Assad does in Syria. Preston recognizes the similarities about foreign dictatorships, Franco had Italy and Germany, Assad has Iran and Russia. The ME he says is about oil and “war on terror” according to Western rhetoric. He does not say Spain was about “stability and avoiding war”, and the “threat of extreme left” in the mainstream media at the time. There is no great difference. Then as now to a few people it was also about democracy. Sidestepping the emphasis about comparing the motivations of volunteers in Spain and Syria. The last sentence should be the first one, because it is the goal Preston is aiming for … “After all, from September 1939 onwards …. the fight of the volunteers in Spain had become the fight of the majority of British and French citizens. There will be no equivalent whatever with the result of the war in Syria.” That is exactly the point, there will. In the 1930s most people and the mainstream media did not see fighting in Spain as essential to fighting the rise of right wing authoritarianism, instead they saw it as a dangerous sideshow in a backward counttry. This is the same shameful mistake being made today about the courage of the Syrian people. The defeat of democracy in Syria and the lack of support for the Arab Democratic uprising in general after 2011, will be seen as the beginning of the collapse of Western democracies. We are undermined by our own elites who have too much wealth, power and vested indifference to the majority. Just as in the 1930s. Preston is an example of confidence overtaking expertise.

[…] on the historian Paul Preston’s article https://albavolunteer.org/2016/06/spain-and-syria-beyond-superficial-comparisons/comment-page-1/#… […]

His expertise on Spain, does not imply accurate comparisons without corresponding expertise on Syria. Without considering the role of “volunteers”, even without this, his article is strange.

Spain before Franco was only ever a semi democracy, governed by a land owning and business elite backed by the Catholic Church. Preston knows better than anyone the lack of control the new Popular Front Government of 1936 had over the state. The so called “rebels” controlled the vast bulk of the effective parts of the Spanish Army, with the unreserved support of Fascist Italy and Germany. Franco while being termed a “rebel”, actually controlled the military apparatus of the state as Assad does. Franco was actually protecting the interests of a very well established Spanish elite, just as Assad does in Syria.

Preston recognizes the similarities about foreign dictatorships, Franco had Italy and Germany, Assad has Iran and Russia. The ME he says is about oil and “war on terror” according to Western rhetoric. He does not say Spain was about “stability and avoiding war”, and the “threat of extreme left” in the mainstream media at the time. There is no great difference. Then as now to a few people it was also about democracy.

Sidestepping the emphasis about comparing the motivations of volunteers in Spain and Syria. The last sentence should be the first one, because it is the goal Preston is aiming for … “After all, from September 1939 onwards …. the fight of the volunteers in Spain had become the fight of the majority of British and French citizens. There will be no equivalent whatever with the result of the war in Syria.” That is exactly the point, there will.

In the 1930s most people and the mainstream media did not see fighting in Spain as essential to fighting the rise of right wing authoritarianism, instead they saw it as a dangerous sideshow in a backward country. This is the same shameful mistake being made today about the courage of the Syrian people.

The defeat of democracy in Syria and the lack of support for the Arab Democratic uprising in general after 2011, will be seen as the beginning of the collapse of Western democracies. We are undermined by our own elites who have too much wealth, power and vested indifference to the majority. Just as in the 1930s. Preston is an example of confidence overtaking expertise.