Rejecting the Cold War Alliance with Franco

In 1949 Harold Ickes, the Secretary of the Interior under Franklin Roosevelt, described General Francisco Franco as a “mimic of Hitler” whose regime “chokes the breath out of liberty in a police state.” Four years later, The Christian Century, a liberal Protestant magazine, called Spain “that pathetic remnant of medievalism.” The Spanish Civil War had ended years earlier, but the debate over its significance, and over how to deal with the fascist government which its outcome established, continued long afterwards.

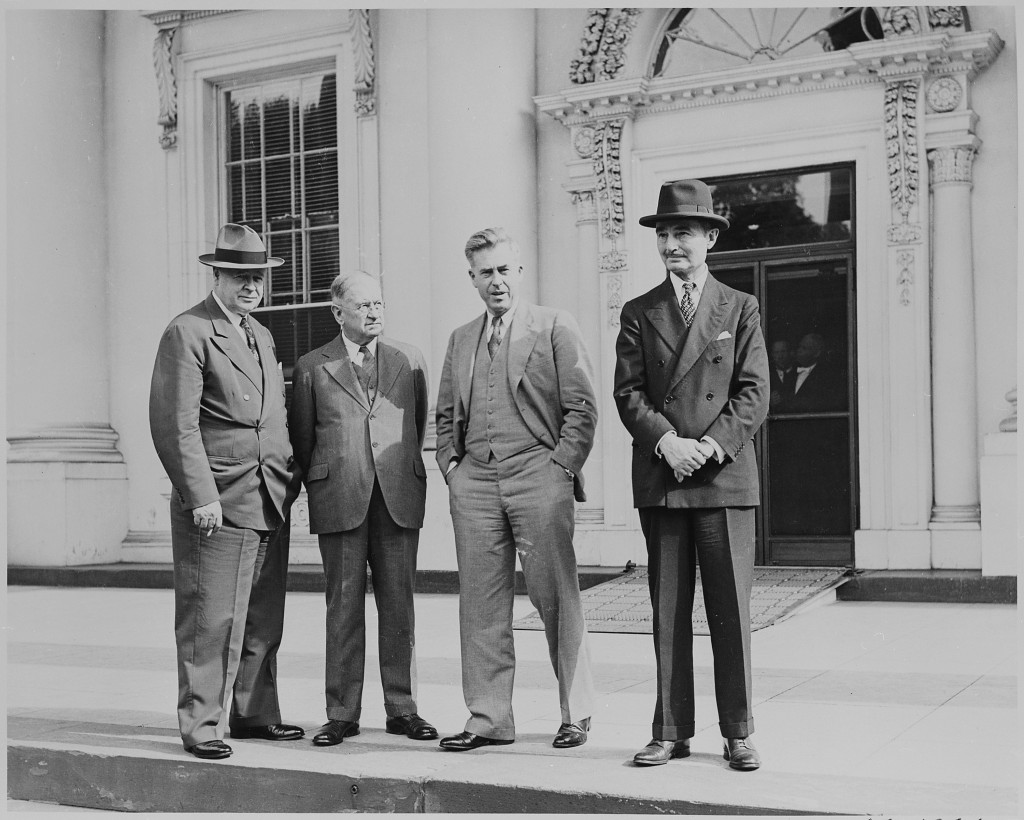

Harold Ickes, Henry A. Wallace, and two other men standing in front of the White House during ceremonies marking the visit of Prince Abdul Ilah of Iraq to the United States, 8 May 1945. Photo Abbie Rowe. National Archives and Records Administration.

President Harry Truman claimed to be building a postwar democratic alliance against Communism, but powerful forces worked to include undemocratic Spain in that alliance. Franco won the Spanish Civil War in large part due to the support he received from Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany—nations that the United States and its allies went on to fight World War II. Truman supported United Nations resolutions in 1945 and 1946 keeping Franco’s Spain out of the world organization and canceling full diplomatic recognition of his regime, and under the President’s direction the 1947 Marshall Plan to rebuild war-ravaged Europe also excluded Spain. However, the U.S. tolerated the presence in Washington of lower-level Spanish diplomats, who hired well-connected lawyers and lobbyists and cultivated relations with the Catholic leaders, right-wing legislators such as Sen. Pat McCarran, Pentagon planners, and selected U.S. exporters. By the end of 1947, important members of Truman’s administration sought a new policy of military cooperation with Franco to counter the alleged Soviet threat to western Europe, and by early 1950 the Senate had voted to extend economic aid to Spain.

U.S. policy toward Spain switched decisively after the outbreak of the Korean War.

U.S. policy switched decisively, however, after the outbreak of the Korean War, as Secretary of State Dean Acheson supported a U.N. resolution in late 1950 ending the ban on recognition of the Franco regime, and ever-increasing economic credits began to flow to Spain. British and French opposition kept Spain out of the nascent North Atlantic Treaty Organization, but in mid-1951 the U.S. began formal negotiations with Spain for a mutual defense agreement. The Pact of Madrid, signed in 1953, provided $1.4 billion in U.S. military and economic aid to Spain over the next 10 years in return for naval and air bases for American forces; most scholars agree that this infusion of cash helped perpetuate Franco’s reign. U.S. leadership facilitated Spain’s entrance into full U.N. membership in 1955, as part of a bargain which also saw the admission of fascist Portugal, neutral Finland, Soviet-aligned Bulgaria and Romania, and 11 other nations. The symbolic high point of the U.S. alliance with Franco came in December 1959, when President Eisenhower literally embraced the Spanish dictator in Madrid.

Many American progressives in the late 1940s and early 1950s recoiled against this gradual realignment of the U.S. toward the Franco dictatorship. Some of this opposition is well-known. For example, The Nation magazine coordinated a 1946 campaign by liberal groups to isolate the Spanish government diplomatically, a campaign which dovetailed with Truman’s initial policy. Nation editor Freda Kirchway hired the former cabinet member of the Spanish Republic, Julio Alvarez del Vayo, as foreign editor, so readers were regularly reminded of the consequences of the Spanish Civil War. Two other American voices of dissent were The Christian Century, generally considered the nation’s most influential Protestant magazine, and Ickes, who was described by The New Republic in 1949 as “America’s most venerable progressive.” Examining what these two voices—both of which were critical of Communism and the Soviet Union—wrote and said about Franco’s Spain and U.S. policy reveals many common elements as well as some intriguing differences as to why these progressives felt so strongly and how they made their case to readers.

The 1953 Pact of Madrid provided $1.4 billion in U.S. military and economic aid to Spain.

Like many American liberals and progressives, when Franco launched his rebellion on July 18, 1936, neither Ickes nor The Century supported direct aid or even the sale of armaments to republican Spain. They wanted the United States to stay out of Europe’s quarrels and believed that aiding one side in any way would draw the nation into war. Ickes soon changed his mind. By 1937 he wrote that the refusal of the State Department to issue passports for an ambulance corps to help the Loyalists “makes me ashamed.” The following year he appealed to FDR to lift the embargo on the sale of weapons to the Loyalists, and he told the President that the failure to do so “constituted a black page in American history.” After the Loyalist defeat, Ickes became honorary chairperson of the Spanish Refugee League Campaign Committee, which raised funds for the resettlement of those fleeing the Fascist regime.

The Christian Century in the 1930s certainly supported the Spanish Republic against the fascist uprising. In a string of editorials, the magazine stated that Franco’s open embrace of fascism, including the outlawing of strikes and the reversal of land reform, should increase support for the elected government. Nevertheless, while arguing that under international law nations could sell weapons and provide aid to a sovereign government, such as the Spanish Republic, The Century applauded FDR’s announcement that the U.S. would stay out, adding, “we can and must avoid armed intervention in quarrels not our own.” While later open to suggestions that U.S. neutrality laws be changed to allow weapons sales to the Republic, it was not until 1939—when the war was all but lost—that the editors retroactively criticized the State Department for vetoing aid to the Loyalists.

The Century urged Protestants to reject out of hand the Pope’s invitation to join a world-wide organization to fight communism.

The Protestant magazine’s most significant contribution to an analysis of the Spanish Civil War was its characterization of the conflict as a “holy war”—and its use of that term was entirely negative. Countering Spanish monarchists and Catholic officials who declared that Franco’s revolt was necessary to save Europe for Christianity, the editors in August 1936 denounced those “whose idea of a Christian social order is an absolute monarchy defended by a Pretorian guard, a feudal system of land ownership, and Catholic unity enforced by the inquisition and the police power of the state.” The Century urged readers to look beyond the slogans of the rebels to see their real threat: “Their cry is against godless communism and materialistic Marxism, but their antipathy toward any form of liberalism, republicanism, or parliamentarianism is no less.” Answering Pope Pius XI’s all-out support for Franco, the editors did not defend Communism, nor did they characterize the Spanish Republic as Communist or Communist-dominated. They did, however, call Communism, despite its evils and drawbacks, “one of many waves of revolt against the concentration of privilege,” in Spain as elsewhere, which “came to include hatred of God because those who claimed most emphatically to represent God seemed to be most habitually on the side of the privileged and the oppressors.” The Century urged Protestants to reject out of hand the Pope’s invitation to join a world-wide organization to fight communism: “It is impossible to consider this new Vatican crusade against communism apart from the struggle in Spain, where the church, after enjoying a monopoly of religion for centuries, has most to lose in property, privilege and prestige.”

The Christian Century continued for the next three years to cover the civil war, with steadily increased outrage at the support for Franco by Italy and Germany which underlay his success, the escalation of attacks by their weapons and soldiers on Spanish civilians, the oppression of Spanish Protestants by the Franco-Catholic alliance, and the “betrayal” of the Republic by Britain as it manipulated world-wide “neutrality” efforts in favor of the fascists.

Both Ickes and The Century, of course, supported the American and Allied cause during World War II, with Ickes even suggesting to FDR that the U.S. invade Spain as part of this anti-fascist struggle. Thus, they, like many other American progressives, expressed visceral outrage after the war ended that the Allies would temporize with the Spanish dictatorship that was so closely identified with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

Typical among the editorials in The Christian Century was “Franco and the Marshall Plan” in 1948. Noting Congress’s pressure on Truman to extend funding to Spain, the editors asserted that the President, too, bore responsibility for this betrayal of democracy because of his efforts to forge an anti-Communist alliance with the Vatican through envoy Myron Taylor. The secretive Taylor mission, which included meetings with officials in Madrid as well as in Rome, not only violated Woodrow Wilson’s standard of “open covenants openly arrived at,” but demonstrated, declared the editors, the “seesaw pattern” of U.S. diplomacy. That is, the U.S. had first hoped to use Hitler and Mussolini against Communism, then embraced the un-democratic Soviets during World War II, and then reached out to “a motley company of undemocratic and anti-liberal forces—first the Vatican itself, then a reactionary and unpopular government in Greece, then Franco.” Three years later, as the preliminary framework for a deal with Spain was signed, the magazine lamented that the U.S. had become “the partner and guarantor of fascist reaction. But what does Washington care about that, so long as the Pentagon gets more bases?” The Century placed its criticism of this new friendship with Franco in the context of the magazine’s opposition to U.S. Cold War policies, especially its military posture in Europe threatening war against the Soviets.

Ickes, after his 1946 resignation from Truman’s cabinet, for three years wrote a popular thrice-weekly syndicated column, and then the self-styled “curmudgeon,” at age 75, continued his punditry with a weekly column in The New Republic until his death in February 1952. Ickes devoted more space to Spain in his essays than to any other foreign policy topic aside from the Korean War, and almost as much as to his fervent denunciations of McCarthyism. Franco’s Spain was, for example, “Fascism indecently naked,” which “spends more than 50 percent of its revenues, wrung from a half-starved population, to maintain an army of 422,000 men.” These soldiers, in turn, “constitute a privileged class whom this mimic of Hitler coddles to keep the Spanish people in dire poverty.” To be sure, Ickes did not hold out the Soviet Union as a model to which Americans should turn: we “should have no truck with either Communism or Fascism.” Nevertheless, in 1949 he observed that “Fascism, which of course includes Nazism,” has been far costlier to the U.S. than Communism, and two years later he reminded readers that “Russia had sent what aid she could to the Loyalists” while the U.S. “stood coldly by.”

Like The Christian Century, Ickes castigated the Truman administration for claiming it opposed Franco while surreptitiously working to warm up relations. “To recognize the Slave Spain of Dictator Franco would be an act of cynicism that the United States could not live down in 100 years,” Ickes wrote in 1949, adding bitterly that it was “military minds” who were “managing our foreign policy these days.” Ickes denounced the “State Department Shell Game” when the U.S. abstained on a U.N. vote about recognition of Franco’s government. Ickes, too, was especially incensed that the administration wanted Spain in NATO, as he argued that including Franco in the alliance would alienate true democrats in western Europe and that insolvent Spain would become a sinkhole for American tax dollars. Ickes linked U.S. actions in the early 1950s to Germany’s and Italy’s deeds in the 1930s: “We are making it possible for some future historian to write that, while it was the material help that Hitler and Mussolini supplied to Fascist Franco that made it possible for him to win his rebellion, it was the financial and diplomatic assistance freely supplied later by the greatest republic in the world that enabled Fascist Franco to retain power by the brutal suppression of the Spanish people.”

The Christian Century added specifically Protestant arguments in opposing the rapprochement with Franco. Again and again the editors condemned the Vatican’s and Franco’s pronouncements that religious liberty in predominantly Catholic countries should be restricted to Catholics. For example, they cited a 1948 Jesuit publication from Rome, endorsed by Spanish bishops, which stated that only “truth” had rights, so Protestants in Spain “shall not be allowed to propagate false doctrines.” The 1953 concordat between Franco and the Vatican formally ratified this approach, with the Spanish dictator prohibiting any expression that might “perturb the safe and unanimous possession of religious truth in this country.” In other words, not only did Spain reintroduce Catholic teachings into all levels of education and pay Catholic officials from state funds, but it outlawed the dissemination of Protestant and other non-Catholic ideas.

As part of its brief against this clerical-fascism, The Century publicized the harassment faced by the 20,000 or so Spanish Protestants: defacement and vandalism of churches, physical attacks against people attending Bible classes even in private homes, arrests during Protestant funeral services, and so on. The editors quoted one prominent New York minister who declared, after a 1948 fact-finding trip, “as a Protestant clergyman I would prefer today to be preaching in Prague behind the iron curtain than in any city in Spain.” (This editorial appeared just below one entitled “Church Unrest Behind Iron Curtain,” which reported on arrests of Lutheran ministers in Hungary and on the forced resignation of Bulgaria’s Orthodox patriarch. The Christian Century was equally critical of religious persecution in the Soviet bloc and in Spain.)

The Century also highlighted Catholic dissent from Franco’s regime, to show that Catholics could overcome the bonds between the Vatican, political autocracy, economic inequality, and social conservatism. In 1951 the magazine reported that Basque priests criticized the Catholic hierarchy’s loyalty to Franco, despite the nation’s move toward economic disaster. (The editors added that Basques had resisted the Inquisition and held out the longest during the Civil War.) That same year The Century urged subscribers to financially assist the independent American Catholic weekly, Commonweal, as that magazine had suffered from deviating in 1938 from the Vatican line on Franco. Just as The Century saw Franco’s Spain as a “remnant of medievalism,” it also saw it as a focal point in a still-unfinished Reformation, hoping to win over dissident Catholics to its views of religious freedom and social progress.

The Christian Century recognized the interconnections between American domestic and international issues during the Cold War, noting, for example, that Franco’s main advocate in the Senate—Nevada’s Pat McCarran—also headed the Senate Judiciary Committee, on which the notorious Joseph McCarthy sat. A 1951 editorial, “Senator Begins War Chant,” observed that McCarran tied efforts to obtain more funds for Spain to cries that war with the Soviets was inevitable and that investigations against internal subversion must be increased. Among these allegedly subversive organizations was the North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, whose executive secretary in the 1930s had been Congregationalist minister Herman Reissig. The Century ran Reissig’s 1951 commentary, at the height of McCarthyism, in which he not only attacked the witch-hunt but stated that Communists and those who worked with them on anti-fascist and pro-labor issues in the 1930s and 1940s were correct. “It is time,” he wrote, to “say that Americans who supported the Spanish republic against the Hitler-Mussolini-Franco alliance were doing what they ought to have done.” Reissig did make clear his disagreement with Communism, however, asserting that the 1939-41 Hitler-Stalin pact exposed its bankruptcy. Ickes, too, tied growing support for Franco to anti-Communist hysteria. He labeled McCarran a “lackey” for Franco while simultaneously assailing “the notorious McCarran thought-control bill” which established the Subversive Activities Control Board.

Ickes devoted more space to Spain in his essays than to any other foreign policy topic aside from the Korean War.

Ickes’s most forceful criticisms of ties to Franco invoked World War II. Such ties constituted “a betrayal of democracy and a repudiation of all that we fought for and won against Franco’s fellow dictators, Hitler and Mussolini.” While the U.S. did not go to war with Spain during the global conflict, Ickes repeatedly pointed out that Franco hoped that the Axis powers would defeat the Allies. “Can it be forgotten,” he asked rhetorically in 1949, “that Franco sent his soldiers into Russia when that temporary ally of the democracies was hard put to beat off the German hordes?” And then in 1951: “Franco’s desire to help Hitler and his inhumane treatment of Allied soldiers who sought refuge in Spain during World War II were notorious.”

In a half-dozen columns, Ickes aimed his sharpest barbs at José de Lequerica, Franco’s postwar representative in the U.S. Ickes expressed outrage that the State Department allowed this fascist agent to operate freely in the U.S., despite having no formal diplomatic credentials, and despite his overt anti-American actions during World War II. Lequerica “was Franco’s Ambassador to France during the dishonorable days of Vichy,” referring to France’s wartime government that was in reality subservient to Germany. “There he [Lequerica] was on close terms with Hitler’s intelligence service, while Franco was servicing Nazi submarines. After Japan had struck its dastardly deed at Pearl Harbor, de Lequerica ostentatiously gave a dinner to Japanese and Nazi guests to celebrate the event.” Historian Stanley Payne, in Franco and Hitler (2008), labels Lequerica “a pronounced Naziphile” who earned his nickname in France as “minister of the Gestapo.”

Ickes’s campaign against Franco and Lequerica yielded enthusiastic letters from readers, including leaders of Americans for Democratic Action, a liberal group generally supportive of Cold War policies but appalled at Franco’s popularity with U.S. officials. One Spanish exile in the U.S. provided Ickes with an English translation of the newly-published memoirs of a former Franco official who had worked alongside Lequerica in France. Ickes devoted a full column to these excerpts, which pronounced Franco’s ambassador as “more German than the Germans.” However, no amount of reminders about Franco’s aid to our World War II enemies could deter Congress and the Truman administration from their embrace of the Spanish dictator.

The Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives have long called attention not only to the heroism of those who fought for the Spanish Republic and against fascism, but to the broader implications of that conflict for the world. The unwarranted suffering of many Lincoln vets from McCarthyite repression has become an integral part of this story, as Washington again abandoned the struggle for democracy in Spain. The participation of Harold Ickes and of The Christian Century in the post-World War II campaign against recognition of and aid to Franco’s dictatorship—unsuccessful though it was—reminds us that the issue resonated far beyond the ranks of the Veterans, and that not only Communists or “Popular Front” groups passionately opposed the Spanish dictatorship. In the case of The Christian Century it extended even to those who had believed in the 1930s that the U.S. should stay entirely aloof from Europe’s military affairs. Ickes, meanwhile, based his fervor on a determination to rectify that “black page in American history,” when the U.S. allowed “neutrality” to be manipulated on behalf of fascism.

While the Spanish Civil War and the subsequent controversy over Franco are sometimes portrayed as conflicts between “religion” and “secularism,” the Protestant Christian Century reminds us that Spanish fascism represented only one religion—and its most backward-looking version at that. Ickes’s emphasis during the Cold War on viewing the Spanish Civil War through its impact on World War II highlights the intellectual somersaults that U.S. officials performed to justify an alliance with Franco. As Ickes and The Christian Century editors engaged with the long-term repercussions of the Spanish Civil War, we see that arguments about the past became arguments about the present, and vice versa—just as is true today.

Robert Shaffer is Professor of History at Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania.

What Pres. Truman and the rest of our government did disgusts me. My uncle died fighting the Germans;but all the miserable forms of government are still alive and well and killing people; even their own people. China and Russia have both taken territory recently.