Book Review: Petals and Bullets

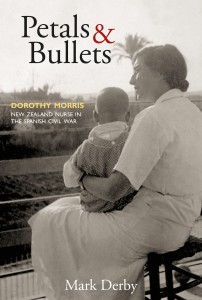

Mark Derby, Petals and Bullets: Dorothy Morris: New Zealand Nurse in the Spanish Civil War (Brighton/Toronto/Chicago: Sussex Academic Press, 2015).

Mark Derby’s biography of Dorothy Morris, a New Zealander who answered a notice seeking nurses for Spain when she was working in London in early 1937, is a fascinating account of a determined woman who was “anti-fascist to the bone.” His book adds to the small but growing number of biographies of women involved in the conflict that drew volunteers from all over the world.

Mark Derby’s biography of Dorothy Morris, a New Zealander who answered a notice seeking nurses for Spain when she was working in London in early 1937, is a fascinating account of a determined woman who was “anti-fascist to the bone.” His book adds to the small but growing number of biographies of women involved in the conflict that drew volunteers from all over the world.

Born in the small town of Cromwell on the South Island of New Zealand in 1904, and characteristic of her independent nature, she decided against finishing a university degree and chose to pursue nursing, a questionable career for a well-educated girl. Nursing was regarded then as a job requiring little more expertise than a housemaid. Her wartime experiences would demonstrate amply that a highly trained and efficient nurse was anything but unskilled. She left for Europe when she was 30 years old after passing her nursing examinations with honors.

After being accepted for wartime service, Dorothy travelled to Almería with the London University Ambulance Unit under the auspices of Sir George Young. Over the next few months she moved with the unit frequently, setting up hospitals in poor villages, with filthy houses to clean, often with no water and no light. Moving on to Extremadura, a Nationalist stronghold, she worked as Head Nurse, looking after the health of the members of the 13th Brigade. Nationalist air raids caused terrible civilian injuries and Morris was horrified when she first saw fractured limbs encased in Plaster of Paris and was not allowed to dress them. Many medical advances were made during the war and the treatment of fractures was a consequential one.

Dorothy wrote in frustration to her family: “you just can’t teach a Spaniard anything.”

One of Dorothy’s duties was to teach acceptable hygiene standards to the “Spanish girls” working for her and she wrote in frustration to her family: “you just can’t teach a Spaniard anything.” Later in her time in Spain, however, as her experience working with Spanish doctors grew and her Spanish improved, she became renowned for her skills in training others. One of her colleagues noted that her disregard of class distinctions made it evident she was not born in England.

Recruited by the American Quakers in July 1937, Morris became Head Nurse at the newly formed Hospital Inglés de Niños in Murcia where she started her long association with the Quakers and working with children, during the war and later among the refugee camps in southern France. When the Republic fell, thousands of Spaniards fled Franco’s Spain to be marooned on the beaches across the border (a terrible situation being repeated along the Mediterrranean today as displaced people flee the Syrian conflict). Morris admired the Quakers enormously and some became close friends, although she said, “I never will be religious in the strict sense of the word.”

At times, the stress of war affected her health and morale and she was given brief respites in Paris but she continued to undertake her commitments with fierce determination and skill. In February 1939 she and her colleagues were given terse instructions from Friends House to return to England on a British naval destroyer before the expected Republican surrender. “I left only because I had to,” she said defiantly.

In London, she gave talks and visited the cinema in between “thinking how lovely it would be to see Chamberlain and Co hanged, boiled and quartered.” In April 1939 she was relieved to be asked to go to Perpignan to head the International Commission’s aid efforts for the Spanish refugees in France. Working with her Quaker colleagues, she also spent days on the road traveling between Paris and far-flung refugee projects, sleeping for days at a time in a motorized horse-box on a blow-up mattress.

Forced to flee again after the German invasion of France, Morris spent much of the war years in London supervising workers in a military equipment factory. In 1944, she was sent to a displaced persons’ camp near Cairo where she contracted such a high fever it was thought she would die. In one of those extraordinary war-time coincidences, Dr Doug Jolly, a colleague from the Spanish war and a compatriot also from the small town of Cromwell, arrived at the hospital with a new life-saving drug—penicillin—and she recovered.

In 1946, after working for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) in Germany, Morris returned to New Zealand “gaunt and exhausted” where she was reunited with her family. But she found the country she had left 12 years earlier “insular” and went back to England a year later where she lived until her final return home at 76.

The tall, strong-featured and opinionated woman who emerges from Petals and Bullets probably deserved her reputation as “formidable”; she was selfless, idealistic and kind-hearted, with a truly steadfast capacity to endure the hardships and tragedy of war. Her years in Spain remained the brightest in her memory.

Mark Derby was aided in his biography by Morris’s letters to her family, held in New Zealand’s Alexander Turnbull Library. Sadly, no diaries or more intimate correspondence survive, giving us limited access to her personal life. Consequently, although her biographer contextualizes her life admirably, she sometimes disappears into the background, particularly in the early parts of the book. He does offer one highly personal and intriguing assertion (delivered almost as an aside)–that she concealed secret documents for the French Communist Party in her vagina as a price for a relief trip to Paris. Was this a common requirement for women working in these conflict zones? Perhaps it was a subject Derby felt unable to pursue.

Sylvia Martin is an Australian biographer and literary historian. Her next book, Ink in Her Veins: The Troubled Life of Aileen Palmer will be published by UWAP (University of Western Australia Publishing) in March 2016. Aileen Palmer, daughter of prominent Australian writers, Vance and Nettie Palmer, served as secretary and interpreter in the first British Medical Unit to go to Spain in 1936.