The Legacy of Spain and the Lincoln Brigade

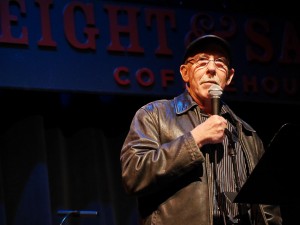

Speech given at the 79th Annual Celebration of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Berkeley, California, November 8, 2015.

All my life I’ve known about Spain. I grew up singing Freiheit and Viva la Quince Brigada and Los Cuatro Generales, and knew the names of some of the places in Spain where the big battles were fought. I owe a lot to my parents, and to the culture they helped create. They didn’t go to Spain, but they were brave people nonetheless. When Paul Robeson went to sing in Peekskill, my dad was one of the union members from New York City who lined the roads to protect people from the rocks thrown by the fascists of upstate New York. In 1953, the year the Rosenbergs were executed, they brought my brother and me here to Oakland, where I grew up. That’s why I’m an Oakland boy, and not a Brooklyn boy.

All my life I’ve known about Spain. I grew up singing Freiheit and Viva la Quince Brigada and Los Cuatro Generales, and knew the names of some of the places in Spain where the big battles were fought. I owe a lot to my parents, and to the culture they helped create. They didn’t go to Spain, but they were brave people nonetheless. When Paul Robeson went to sing in Peekskill, my dad was one of the union members from New York City who lined the roads to protect people from the rocks thrown by the fascists of upstate New York. In 1953, the year the Rosenbergs were executed, they brought my brother and me here to Oakland, where I grew up. That’s why I’m an Oakland boy, and not a Brooklyn boy.

When I think about the impact of Spain on my life, I think about the people who went and fought there, and what they taught me. Some of them I knew personally, and some taught me by example. They all taught me about how to conduct a life dedicated, not just to opposing injustice, but to fighting for a different world, for a vision of a just society, a socialist society.

Today I work with California Rural Legal Assistance, as a photographer and a journalist. Growing up in Oakland, I didn’t know much about life in rural California, or who farm workers are and the work they do. But I come from a union family, so when I got back from Cuba in the early 70s, full of revolutionary enthusiasm, the place where I thought I could fight for real change here was the farm workers union. I went to work, learning from people like Eliseo Medina the nuts and bolts of how to organize strikes, win union elections, go on the boycott – the basic toolkit of working class struggle.

There I met Ralph Abascal, who had helped to organize California Rural Legal Assistance. With a nod and a wink, after the lawyers had gone home at the end of the day, our crew of workers and organizers would come in and use the typewriters and xerox machines all night to put together our legal cases against firings and grower dirty tricks. That’s what I loved about CRLA and the way he ran it – it was a part of the workers movement, and its resources were shared. He wanted the union and the workers to fight and survive. It was no surprise to me later to learn that Ralph’s family came from Spain, and that his uncles fought in the Civil War.

I’m not your average photographer. That’s one reason why CRLA and I get along so well, together with our partner in documenting the lives of farm workers, the Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales. The purpose of our work is to create photographs that are instruments or tools for social change. We document workers living in tents under trees and sleeping in their cars when the harvest comes, in Arvin, Coachella, San Diego and Santa Rosa. But we do more than show abuses. Our photographs show workers acting to change those conditions.

One of my favorite quotes is by Alexander Rodchenko, the famous Soviet photographer of the 1920s and 30s. He said, “Art has no place in modern life,” and that we should “take photographs from every angle but the navel.” What he means, of course, is not just that photographs should have a social purpose, but that the photographer should be part of the movements for social change, for revolution.

The most important photographer who not only shared this idea, but lived her life by it, was Tina Modotti. She had a deep connection with the defense of the Spanish Republic. She was an Italian immigrant, from Udine, but she grew up here, in San Francisco. Today they have festivals in her birth town and a foundation in her name in Italy. Here in the Bay Area, though, we hardly know or speak about her. She grew up in North Beach, wanted to become an actress, and went to Los Angeles where she met Edward Weston. Together they went to Mexico just at the height of the artistic ferment of the 1920s, when the revolution was going strong.

She and Weston developed modernism in photography, but she went a step further. She filled their modernistic style with political and social content. And she did more. She joined the Mexican Communist Party, and helped organize the Union of Painters and Sculptors. She took some of the first photographs of huge political demonstrations, and tried to find a visual language that was simple and could inspire people to act.

And as her political commitment deepened, the Mexican government deported her in 1930 to Germany, and from there she went to the Soviet Union, where she went to work for the Comintern. During that time she stopped taking photographs. That’s one of the things I admire most about her. She said, “I cannot solve the problem of life by losing myself in the problem of art.” There are times when the need to act politically is so important that art has to give way. That’s the opposite of what we’re taught in the corporate culture of today, where “art is everything” – that you can’t let mere social justice get in the way.

When the war came in Spain, she went with her lover, Vittorio Vidali, or as he was known in Spain, Comandante Carlos. Modotti was the organizer for Workers Red Aid, helping to free what prisoners they could, and sustain and keep alive those they couldn’t. She worked with Dr. Norman Bethune. Vidali organized the Fifth Regiment, and today when I hear the words to El Quinto Regimiento, that in the “patio de un convento, el partido comunista (in Oscar Chavez’ version) or el pueblo madrileño (in Rolando Alarcon’s version) formo el quinto regimiento,” I think about Vidali and Modotti.

At the end of the war, Modotti was in charge of helping the streams of refugees that filled the roads along the coast, from Barcelona to the French border, as they fled Franco’s advancing troops. I think about her when I see the roads filled with migrants fleeing the bombing in Syria and Iraq today, trying to find refuge in Europe. If Modotti were alive, she would be there. But she would be the first to say that these desperate people can’t use our pity any more than the Spanish refugees could.

Just as we know that the advance of fascism was the root cause of people fleeing Spain, we have to look at the root causes of the flight of migrants today. We have to ask what, or better still, who makes poverty and violence so unbearable that drowning in the Mediterranean seems an acceptable or necessary risk. And of course, it’s not just there. What is causing the poverty and displacement in Honduras or Mexico, that makes migration a necessity for survival? And just as the internment in France that greeted the Spanish refugees was a basic violation of their human rights, and a demeaning humiliation, the Karnes and Hutto detention centers in Texas are a crime against working people that we have to fight today.

After the war Modotti and Vidali separated. Vidali eventually returned to the Free Territory of Trieste, and when it became part of Italy he was elected the Communist deputy from Trieste for many years. Modotti returned to Mexico when Lazaro Cardenas was president, but she was so exhausted she got sick and died. She was never allowed to return to San Francisco, and to her family.

So this lesson of Modotti and Spain is that photography and social change are important and go together, but the most important thing is the objective, which is to fight fascism and change the world.

Spain attracted photographers. We all know the Robert Capa photo of the soldier shot just at the moment when he rises to charge the enemy. Capa made his reputation in Spain. The famous Magnum Photo Agency in New York was organized by photographers who supported, and some who participated, in this huge social upheaval. You can’t see much of those politics there today, though. I did a google search of the VALB archive database, and I found 26 photographers who went to Spain, and that’s not counting the other artists. They didn’t go to take pictures or paint. They went to fight. So Modotti was definitely not the only person who thought this way. But she asked the big question about our role as artists – how to make art serve the cause of social justice, and how to make that the main question – not becoming a celebrity or making lots of money.

When the vets came back from fighting in Spain and from World War Two, California and the Bay Area here, were very different politically from what they are today. Don Mulford was firing teachers for not signing loyalty oaths. The Knowland family ran Oakland. Sam Yorty ran Los Angeles with Chief Parker running the LAPD, including its notorious Red Squad. The growers in the valley had all the power. They had yet to be challenged by the farmworkers historic strike in 1965, the fiftieth anniversary of which we’re celebrating this year.

In my life as a union organizer, before I started work as a photographer and journalist, I met other people who’d fought in Spain. They were part of the unions and movements where I met them. Henry Giler was blacklisted in those bad old days, and became an air conditioning mechanic, before he went back to law school. Then he became a civil rights lawyer, and defended our strikers when I worked for the United Electrical Workers. We were organizing immigrants at the beginning of the huge upsurge that has changed California’s politics so fundamentally.

I met Coleman Persily, because we were both friends of Bert Corona, the founder of our modern immigrant rights movement. Coleman fought in Spain, and then in the 50s he and Bert helped run the campaign for Edward Roybal, the first Chicano elected to the Congress from California since 1879. That was a harbinger of the end of the Yorty years, of the hatred of Latinos seen in the Zoot Suit riots and the Sleepy Lagoon prosecution, and of LA’s reputation as the home of the Open Shop. As we know today, much bigger political changes were to come, and people like Henry and Coleman helped set the stage. Coleman went on to help organize the Canal Street Alliance, which today is Marin County’s main immigrant rights organization.

Through organizing immigrant farm and factory workers, I became an immigrant rights activist and organizer, like them. In those days, it didn’t make you popular, in the labor movement especially, to insist that undocumented workers had rights, and that our unions had to include and fight for them.

Both Henry and Coleman had a vision of justice and equality, which took them to fight in Spain, and which they brought back into the movements here at home. They also brought back a love of the Spanish language and culture, which then became a love for the Mexican people. It’s remarkable how many people came back from Spain and wound up in Mexico itself. Some were like Linni De Vries. She went to Mexico because she was hounded by the FBI, but then loved it so much she become a citizen in 1962. The U.S. government took away her U.S. citizenship a year later.

And then there’s Archie Brown. When I was trying to figure out what it meant to be committed to socialism, and to be a union organizer at the same time, Archie was the person who helped me.

When my youngest daughter was little, her favorite movie was “Newsies” – the musical about the newsboy strike against Pulitzer in New York in 1899. Only later did I learn that Archie too had been a newsie, and helped organize a newsie strike here in Oakland in 1928. Archie became a Red very young, as did many people who went to Spain. He was so visible that the State Department wouldn’t give him a passport, and he had to cross the Atlantic as a stowaway.

When I was just becoming politically aware, at 12, Archie got called by the House Un-American Activities Committee. As he started to speak, refusing to name names, demonstrators, many from the UC campus here, burst into the hearing room and disrupted it. Archie was thrown out. It was the opening of the civil disobedience offensive that eventually led to the students being washed down the marble staircase of San Francisco City Hall. That was the beginning of the end for HUAC.

Archie spent his working and political life in Local 10 of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union. In Archie’s book, the most important political work you could do in a union was to educate rank and file workers, and help them become activists for change, in the union, at work, and in the community around them. When he ran for union office as a Communist, his point was first, to get workers to think about more radical ideas, and second, to challenge the Federal government’s prohibition on electing Communists to union office.

He was successful on both counts, I think. The government indicted him, but the Supreme Court overturned the prohibition. This is important for us to think about. His attitude was that laws that violate the political and labor rights of working people have to be challenged directly, legally in court, and politically out in the world. Today the Supreme Court is about to strike down the laws protecting union membership in contracts for public workers. Archie, running for office deliberately to defy the law, is saying to us, we have to fight.

His other objective was as important. One of the most important reasons why the Bay Area and the cities of the Pacific Coast have a radical political tradition is because of the ILWU. But it’s not just the union as an institution. It’s the fact that the union brought together and educated a body of workers who then worked in political campaigns, civil rights demonstrations, school and workplace integration, and a myriad of other social struggles. And creating and maintaining that active membership was the job of the left-wingers in the union.

That’s what Archie believed. Power and leftwing politics in the labor movement comes from the bottom up, not the top down, and only if there is an organized left fighting for it. In my own working life, I tried to use every strike, every plant that closed throwing workers onto the sidewalk, as an opportunity for us to learn about the nature of the society we live in.

Today in our labor movement we have a crisis, in part because we represent a falling percentage of the workforce. We face a political structure, Republican and even Democratic, that is more hostile towards us than any we’ve seen since the 1920s. But the crisis is also a result of our unions’ failure to propose much more radical measures to advance our interests, and to educate our members so they understand why that’s necessary.

I don’t think Archie learned this way of being a working class activist and organizer in Spain. But I think he shared it with the people who went to Spain from the surging working class movement of the mid-1930s. This was their style of work, what made them so effective. After all, they left for Spain within just a year or two of the San Francisco General Strike, the greatest labor upsurge we’ve ever had here. They made the same choice that Tina Modotti did. Defeating fascism in Spain was the overarching need of the working class movement all over the world, more important even than the union itself. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade is the product of that idea – what made international solidarity such a force that we celebrate it today, eighty years later.

And what they all have in common – Tina, Henry, Coleman, Archie, Vittorio Vidali – and I think everyone here – is that we fight for a more just world, not merely against the injustice of this one. This is why the living memory of the Lincoln Brigade is so important.

Sergio Sosa, a Guatemalan migrant who now directs Omaha’s Heartland Workers’ Center, says: “People from Europe and the U.S. crossed our borders to come to Guatemala, and took over our land and economy. Migration is a form of fighting back. Now it’s our turn to cross borders.”

The experiences of workers migrating from country to country for jobs, or fleeing warfare and repression, testify to the impact of free-market economics and the wars they bring about. But at the same time, these migrants are changing profoundly the culture and social movements of the wealthy countries of the global north. They are one reason why we have a greater opportunity to talk about a vision of a society free from exploitation, a socialist society, than we’ve had for twenty years.

The economic inequality and social cost of capitalism haven’t changed—if anything, they’ve become even more exaggerated. The class conflict at the root hasn’t been eliminated by globalization. In fact, it’s been extended and deepened in country after country.

Many people in our movement, at least in the US, see the cost of this system to our people and hate it. We recognize the common interest of many sections of our society in opposing it. Hating capitalism, even by name, has become popular. In my youth, just using the word capitalism was enough to get redbaited and ostrasized. Now we celebrate May Day, thanks to the ourpouring of immigrants, especially from countries where it’s always been celebrated as the workers’ holiday.

But what is the alternative? Can society be managed on the basis of equality? Can economic development provide a full life for all people, not just more efficient commodity production? What is the vision of the future that can bind together a movement of millions of people, which can produce an alternative culture that can last from one generation to the next?

A radical vision runs counter to the prevailing wisdom of our times, which holds the profit motive sacred, and believes that market forces solve all social problems. If we challenge that wisdom, we won’t get invited for coffee with the President. At the beginning of the cold war, the AFL-CIO built its headquarters right down the street from the White House. Maybe it’s time now to move.

For working people to organize by the millions, which is what we have to do, we have to make hard decisions. People must their jobs on the line for the sake of their future. But the unions of past decades, the activists and organizers who went to Spain, won the loyalty of working people when joining was even more dangerous and illegal than it is today. The left then proposed an alternative social vision – that society could be organized to ensure social and economic justice for all people. We were united by the idea that we could gain enough political power to end poverty, unemployment, racism, and discrimination.

Today our biggest problem is finding similar ways to affect consciousness — the way people think. We have to have a much clearer sense that large-scale social change is possible. The radical vision of those who fought in Spain made the movement here stronger. When our movement lost that vision in the red scares of the 1950s, we lost our ability to inspire. It’s no accident that the years of McCarthyism marked the point when the percentage of organized workers began to decline.

Radical ideas have a transformative power—especially the idea that while you might not live to see a new world, your children might, if you fight for it. In the 1930s and 40s, these ideas were propagated within unions by leftwing political organizations. A general radical culture reinforced them. Today we need a core of activists unafraid of radical ideas of social justice, and who can link them to immediate economic bread-and-butter issues. And since good ideas are worthless unless they reach people, we have to be able to communicate that vision to working people as broadly as we can.

We are not at the end of history. We have to reclaim our history, not discard or forget it. Working people have proposed alternatives to capitalism for over a hundred years—socialism, communism, nationalist economic development, and more. Those who went to Spain were fighting for this vision, as much as they were fighting against Franco.

We are told we must allow millions of people to become casualties of the free market, whether as the unemployed, the hungry and powerless, or the victims of war and oppression. It is up to those who say there is an alternative, not only to proclaim it and advocate for it, but to organize the majority of our people to fight for it.

This is the most important legacy of Spain. If there is to be any alternative, it will only exist because those who don’t benefit from the current system fight to bring a new one into being.