Digging History at Belchite: Civil War Archeology

British and Spanish archaeologists have spent two years investigating Spanish battle sites. American journalist Steve Dinnen joined the dig at Belchite. “We are not here to tell nice stories about the past. The past hurts.”

When archaeologists asked me to help dig up latrines used by Fascist fighters outside of this small Aragon town during the Spanish Civil War, I began doubting the wisdom of volunteering for this adventure. At the site, I discovered luckily that it had been airing out since 1938 when it was blasted to smithereens as Republican forces that included the Abraham Lincoln Battalion battled their way toward Zaragoza.

The latrines, as well as trenches, observation outposts, and farm fields around Belchite, are part of a two-year undertaking mounted by British and Spanish archaeologists to better understand the forces of war that collided here, and across Spain, during the carnage of 1936-39. For me, a journalist from the Midwest, it was an effort to pay homage to Lincoln vets who I had known and who had fought at the very sites where we were digging in September 2015.

This was my way to say goodbye to people I first met in 1996 while writing about their reunion in Spain for The Christian Science Monitor. Among the people in Madrid who I interviewed then were Clarence Kailin, of Madison, Wisconsin and Jacob (Jack) Shafran, a New Yorker.

None of them had an ounce of Spanish blood in them and yet they were willing to lay down their lives for a cause they believed in.

I got to know Jack well, and through him Lincoln vets Harry Fisher and Norm Berkowitz. The three of them had belonged to a team of 11 men from a department store workers’ union in New York City who had volunteered for Spain. Both Norm and Jack were wounded as they fought as infantrymen, or on a machine gun crew, or as they patched frayed field telephone lines as part of the transmisiones squads. Clarence likewise was wounded in Spain.

The three New Yorkers later fought in World War II (Norm was wounded again, in the same leg). Harry wrote a well received book of his days in Spain, Comrades, and in his late 80s went on a speaking tour of Spain and Germany. In the late 1990s I tagged along with him and his family as they visited Spain and wrote about his wartime experiences for The Star Ledger (Harry lived in northern New Jersey). As we entered the 21st century, they passed on; first Harry then Jack, then Clarence and finally Norm. In 2009 I accompanied Jack’s daughter to Spain so we could scatter his ashes on the Ebro River and at the grave of John Cookson.

So my history with these men went back some ways. So did my admiration for them, as none of them had an ounce of Spanish blood in them and yet they were willing to lay down their lives for a cause they believed in – ridding the world of fascism and standing up for the common man.

Theirs was a noble cause, I thought but it was not until I heard of UK-based archaeologist Salvatore Garfi that I saw a way to honor them by participating in an excavation of the war’s battle sites. Garfi, a research fellow at the University of Nottingham, has long been interested in what is called conflict archaeology – the study of war. In 2014 he decided that the relatively high level of international interest in the Spanish Civil War and the International Brigades that fought there merited a review from his perspective. Thus was born the International Brigades Archaeology Project.

Archaeology allows historians to gather a very different understanding of war from that provided by texts or oral histories.

“People will gladly visit IB conflict sites and walk the routes they trod, so why not get involved in a real nitty gritty way, and actually explore those sites through archaeological fieldwork?” Sal said of his interest in Spain. Speaking in 2014 to the BBC, Garfi said that he intended to conduct excavations and surveys of the landscape in order to build a picture of what happened, and compare that to written evidence of a battle “so we can question the truth of those accounts.”

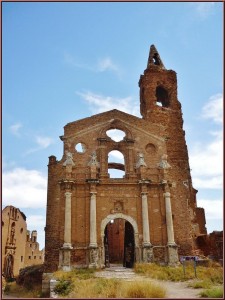

Garfi and his Spanish counterparts focused on Belchite. It was there that the Republican Army of the East, joined by the XI International Brigade and the XV International Brigade—of which the Lincolns were part—decided in August 1937 to attack. Their aim was to push the battle line toward Nationalist-held Zaragoza, and also to divert Nationalist troops from other battles. Between August 24 and September 7 1937, some 160,000 troops — evenly split between Republicans and Nationalists — fought over a miles-long front with Belchite as a centerpiece. The town was mercilessly pounded by artillery, rifle, and mortar fire.

After entering Belchite, Norm Berkowitz recalled to me that he ducked into a peasant’s hut because enemy snipers awaited anyone venturing into the street. He and other troops advanced their position by using the butts of their rifles to smash through one flimsy hut wall and into the next. Republicans made strong advances along the offensive line, but got bogged down in Belchite by an estimated 7,000 Nationalist troops. They finally routed them on September 7, 1937.

Many Spanish cities were heavily damaged by the war. Dictator Francisco Franco preferred to leave Belchite as it was, as a “living” monument (and perhaps as a reminder to Spaniards of what might happen if they challenged his dictatorship). The town of new Belchite rose adjacent to the ruins, which for decades have been open for inspection by anyone.

We diggers, as I called the team, planned to comb through selected parts of the battle area, looking for remnants of munitions, food, clothes — pretty much anything that soldiers would have left behind and scavengers had not already carted off.

We numbered about two dozen. There were three Spaniards who were paid staff, and they were aided by more than a dozen Spanish volunteers, mostly university students studying archaeology. There were other diggers from England and other European nations, and four Americans. I alone had any direct tie to a Lincoln vet.

Our first day was spent to the north of Belchite, walking around treeless hillsides in search of the detritus of war. Team leaders had maps showing trench locations during the battle—who knew they kept such records?—and directed us to fan out and keep our eyes glued to the ground for anything that looked out of place. Like pieces of shrapnel, which we found in an abundance. Some were from grenades, others from mortar rounds and still more from artillery shells. When we found something we would plant a small stick in the ground and wait for it to be inspected by our leader, Alfredo González-Ruibal.

“Yes, this is a 9mm cartridge from a fascist rifle,” he would say. Or, this is a German grenade fragment. From rusted, dirt-caked pieces of war that were sometimes the size of a thumb nail, he could discern the difference between Fascist and Republican munitions.

Alfredo, a senior archaeologist with Incipit, a branch of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), likewise knew the difference between a remnant of a shoe or boot worn by a Nationalist and a Republican. Ditto for glass: did those shards come from a bottle of wine, or a bottle of absinthe?

These subtle differences were key to determining the situation that the troops faced when they were in trenches that sometimes were just 100-200 yards away from the enemy. As Alfredo said, archaeology allows historians to gather a very different understanding of war from that provided by texts or oral histories.

“We deal with the materiality of conflict,” he said, “from the entire landscape that was experienced by fighters to the cartridges they were shooting….This is not so much about discovering the past as about understanding how history was experienced by its protagonists.”

From what we were able to piece together (both in 2015 and during an earlier dig), Alfredo and his team have assembled a “fairly detailed picture of trench warfare,” which he said is pretty much absent in books and testimonies about the war. “We know more about the little details of the everyday life on the front line,” Alfredo continued. “The difficulties and importance of keeping clean and healthy, the diet (we found many sardine cans), the problems with faulty munitions and explosives.” On that last point, we clearly had an example when, scouring that field a few days later, British college student Harry Guild came across an unexploded mortar round. This same field had earlier given up a 155mm artillery shell that was identified as Italian.

The next day we went to the latrines. They were built by Fascist troops who had taken over a seminary that stood south of town. As elsewhere, the idea was to dig through the remains to see what might have been left behind. First we had to clear brush and topsoil that had overrun the remains. Then we carefully dug to the floor of the latrine, so the experts could photograph the scene and make note of what they found.

As a rookie non-expert, I helped with weed and dirt removal. This was bone-dry soil laced with heavy rocks. We used picks, hoes, and spades and by day’s end were covered with dust and sweat and aching muscles. I hadn’t worked so hard since bailing hay in Missouri as a teenager. Archaeology, I learned, was grueling.

Our toils were suddenly interrupted when word came that Alfredo and the other professionals were being evicted from apartments they rented from the town. A new mayor had recently been elected, from the conservative Partido Popular (People’s Party), and he wasn’t happy with us nosing around. He couldn’t stop the dig, but he could disrupt our efforts.

The new conservative mayor wasn’t happy with us nosing around.

Alfredo, who knows of mass graves of civilians and military personnel in the area and would like to continue to work in and around Belchite, said it is obvious that the wounds of the war have not yet healed. “Many people find archaeological work on the topic uncomfortable, to say the least,” he said. “But this is the job of the social scientist. We are not here to tell nice stories about the past. The past hurts.”

Once the leaders secured new housing, we pressed on to a field immediately adjacent to the Belchite ruins, finding more glass shards and munitions. It was here that the story of the Lincolns hit home, as a team leader noted that soldiers in that field had taken fire from Fascist machine guns mounted both in a church bell tower and the town’s main gate.

Jack Shafran told me years ago that he and a comrade had somehow gotten ahead of the rest of the troops at Belchite and found themselves in a field, pinned down by gunfire. But all the bullets were landing behind them. It seems they had advanced so close to the bell tower that the machine gunners could not lower the gun barrel to get a bead on them. Jack and his pal buried themselves as deeply as they could behind a furrow in that field and waited for nightfall.

Here I was, 78 years on, standing precisely where my friend had beaten certain death! I’ll never know the terror of bullets flying overhead, or come close to the experiences that Jack and so many other Lincolns had in Spain. But that day I touched the same earth they had touched, and I knew that as they fought in a large way for a better world I was working in a small way to continue their effort.

My wife figured it out, when I called her back home to tell her about the Mayor’s efforts to thwart us. “It’s when they tell you to stop digging that you need to keep digging,” she said.

For more insight on Belchite and the archaeological work being done, visit IBAP: https://sites.google.com/site/internationalbrigadesproject/

Geoffrey Billett, a retired mental health worker from Southwest England, participated in the dig at Belchite in September 2015. An accomplished photographer, he assembled this series of photos of the work there:

http://sannyassa.co.uk/returning-to-where-we-have-never-been/

Steve Dinnen lives and works in Des Moines, Iowa. He travels to Spain frequently and has long held an interest in the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.