The Wings of the Republic: Spain’s Women Pilots

Mari Pepa Colomer and Dolors Vives were the first two women in the Spanish Republic to earn their pilot’s license, working as flight instructors for the Republican Army. Both led lives of legend and enjoyed an uncommon longevity—yet a decade after their deaths, most Spaniards have never heard of them.

From left to right: Dolors Vives, Dolors Vives, Josep Canudas, Mari Pepa Colomer and Adolf Azoy. Carreras-Colomer Archive.

(Versión en castellano.) The history of the Spanish Republican air force is not well known. Even less remembered are the Republic’s two women pilots. Mari Pepa Colomer, who passed away in 2004, had earned her pilot’s license in 1931 at age 17. Dolors Vives, who died in 2005 at age 96, was the second woman to become a pilot in the Republican air force, in 1934. During the Civil War, Mari Pepa and Dolors worked as flight instructors for the Republican Army. Both survived the war and the defeat. Both led lives of legend and enjoyed an uncommon longevity. Yet a decade after their deaths, these women remain unknown to most Spaniards.

It’s said that Mari Pepa first took flight at the age of seven when, like Mary Poppins, she jumped from a second-story window holding an umbrella.

On August 2, 1936, just a few weeks after the rising of military rebels against the Republican government, 23-year-old Mari Pepa doesn’t hesitate to pilot her plane from Barcelona to drop anti-fascist leaflets supporting the Catalan autonomous government, the Generalitat. A few months later, her friend Dolors reaches the rank of second lieutenant. In the next three years Mari Pepa and Dolors conduct hundreds of inspection flights, patrolling the coasts looking for ships, aircraft, and the movement of enemy troops. In the spring of 1939, after the war is desperately lost, they perform final liaison missions to help militiamen and civilians escape to France.

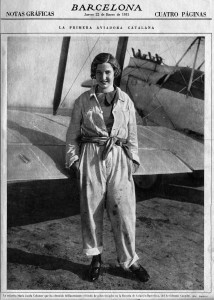

Everything began in May 1930. Mari Pepa Colomer, daughter of a textile wholesaler from the Catalan town of Sabadell, began flying lessons in the aerodrome of El Prat. A (probably exaggerated) tale is told that she had first taken “flight” at the age of seven when, like Mary Poppins, she jumped from a second-story window holding an umbrella. Raised in a wealthy family, from an early age she felt great admiration for Amelia Earhart, the American aviation pioneer. Her father, Josep Colomer, financed the course fees, and after carrying out the statutory 60 hours of flight, Mari Pepa became the first officially licensed woman pilot in Catalonia. Two days later, the news hit the headlines and the cover of La Vanguardia, the most important newspaper in Barcelona.

During the 1930s, when in many parts of Spain cars caused astonishment, airplanes fascinated people to no end.

It is difficult to look at the photo in La Vanguardia without a pang of nostalgia. The image encapsulates the spirit of optimism. In peacetime, aviation was a public spectacle. It was also an essentially bourgeois activity. Only those belonging to a privileged class would join flying clubs. During the 1930s, when in many parts of Spain cars caused astonishment, airplanes fascinated people to no end. They symbolized the future, showcased in flying competitions and displays. Pilots embodied the world to come and their deadly stunts mesmerized spectators. Mari Pepa Colomer became a popular figure. Shortly after the Republic was proclaimed, she flew over Barcelona carrying a three-colored Republican flag. Among her first passengers was Lluís Companys, president of the Generalitat. The pilot José Carreras, whom she met during her training period, and who years later would become her husband, was a celebrity. The press hailed his exploits, which included a solo flight across the Sahara Desert and a successful return to the Canary Islands.

Mari Pepa also amazed the public. In October 1932, the same year her heroine Amelia Earhart completed a solo trip over the Atlantic, the Catalan aviator landed a Zeppelin in Barcelona. It was a big social event. Among those attending was Dolors Vives Rodon, a 23-year old from Valls. Soon, she would follow the same path. In one of her last interviews, she stated that she was lucky twice. First, because her family encouraged her to follow her dreams. Second, because she won one of the few scholarships offered by the Flight Club. “My father, a lawyer, was a man of democratic ideas, very interested in social issues and concerned about living conditions,” she said. “So, when the club Aeropopular was created to popularize aviation (until then basically a military activity) we became members. It wasn’t very usual to see a woman in a plane, even more unusual when she was the pilot. People found it strange.”

A brilliant pilot, Dolors learned quickly. On May 31, 1935 she got her license, number 217, from the National Airport Authority. She went even further than Mari Pepa, when one year later she became the first woman to earn a license for flying planes without engines. This license never reached her. Like many other things in Spain, the bureaucratic process stopped dramatically on July 17, 1936, when the military rebels rose up against the government. The Spanish Civil War had begun.

From one day to the next, pilots who not long before had amazed crowds with innocent tricks became the horsemen of death.

Like a sudden nightmare, from one day to the next aviation changed. Many pilots who not long before had amazed crowds with innocent tricks became the horsemen of death, willing, in the name of “God and Spain,” to unleash hell on public streets and squares. During the war, Spain would be the first country in Europe to discover the dark side of aviation: the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians.

When war erupted, Mari Pepa and Dolors were called to join the army and assigned to work as flight instructors. Their task was almost impossible. They were expected to establish, in a few months’ time, an air force regiment made up of volunteers and militiamen. They trained young soldiers, many of whom were seeing an airplane for the first time in their lives. In this way, with just a few old light aircraft, the future pilots of the Republican air force were born.

In one photograph, we see Dolors Vives in her cabin, inside one of the biplanes in which she taught new pilots to fly. Those who passed the basic course went on to the military base of San Javier, in Murcia. Another group, usually made up of the best pilots, was sent to Kirovabad to continue their training in the Soviet Union.

In one photograph, we see Dolors Vives in her cabin, inside one of the biplanes in which she taught new pilots to fly. Those who passed the basic course went on to the military base of San Javier, in Murcia. Another group, usually made up of the best pilots, was sent to Kirovabad to continue their training in the Soviet Union.

From the USSR came the famous I-15 and I-16 Polikarpov air fighters, which Spaniards nicknamed Chatos [pug-nosed] and Moscas [flies]. These planes changed the course of the war during the siege of Madrid, in one of the few military triumphs of the Republic. In November 1936, after the Republican government moved to Valencia, concerned that the Nationalists would take Madrid, the Republican pilots, helped by the Soviets, were able for the first time to hold their own against the Italian air fighters (Aviazione Legionaria) and the German Condor Legion, saving Madrid from invasion.

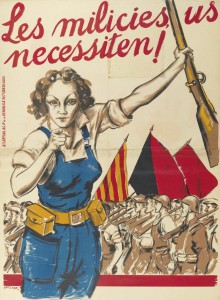

As far as we know, neither Dolors nor Mari Pepa took part in combat missions. Still, their role during the war stands in sharp contrast with the subordinate position of women on the Nationalist side. In Franco’s Spain, the place of women was not in trenches, barricades, or the cockpit of a plane. If we look back to the military propaganda posters, we appreciate a huge difference between the warring sides. The posters illustrate not only a political conflict, but a war of ideas. A famous image drawn by Cristóbal Arteche urges women to take up arms. Les Milicies us necessiten Like a sudden nightmare, from one day to the next aviation changed. Many pilots who not long before had amazed crowds with innocent tricks became the horsemen of death, willing, in the name of “God and Spain,” to unleash hell on public streets and squares. The Militias Need You Like a sudden nightmare, from one day to the next aviation changed. Many pilots who not long before had amazed crowds with innocent tricks became the horsemen of death, willing, in the name of “God and Spain,” to unleash hell on public streets and squares. reads the text in Catalan, with a background that combines the Catalan flag, the red and black flag of the Anarchist CNT, and the red flag of the Marxists.

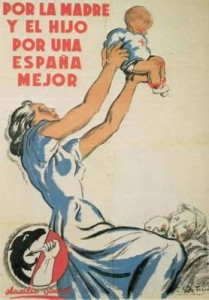

From the other side, an image from the Falange’s Social Aid instructs women to take care of the family while the husband goes to fight: Por la madre y por el hijo, por una España mejor (For mother and son, for a better Spain). Kinder, Küche, Kirche (House, kitchen, church). Hitler’s “3 Ks” had its equivalent in the slogans issued by La Sección Femenina (Women’s Section). This branch of the Falange, led by Pilar Primo de Rivera, proclaimed devotion to the “women’s mission in life” and the “sacred warmth of the family.” The new Fascist woman should engage in “purely feminine” tasks: providing clothes, working in workshops or in stores, caring for returning wounded soldiers, sewing and washing.

Still, the retrograde future that Franco reserved for Spanish women doesn’t automatically turn the Republic into a paradise of gender equality. In the Republican rearguard, women had to win a lot of battles. The emblematic figure of the militant woman, dressed in a uniform of worker’s overalls and armed with a rifle, had been prominent in propaganda. And there was, indeed, a spectacular enlistment of women in the first months after the military coup. Rosario Sánchez, la dinamitera (the dynamite girl), immortalized in a poem by Miguel Hernández, or the mythic Lina Odena, immediately enlisted as volunteers. So did Mari Pepa Colomer and Dolors Vives. But most of the photos we have of women fighters were taken in a relatively short period of time. The iconic images of dozens of anarchist woman in improvised combat vehicles, for example, are from the first months after the Fascist insurrection failed in Madrid and Barcelona. It was a time of spontaneous recruitment, a stage in which the war was experienced as a fiesta, a prelude to social revolution.

Throughout Civil War, however, Republican and anarchist women maintained a double fight: a struggle to transform society and a struggle to change their place in it. Many feminist organizations endorsed the slogan: “Men to the battlefront, women to work.” Quite the opposite of surrender, the slogan claimed that women could maintain production in the factories while their partners stopped the enemy. During this time, even work was understood in military terms, so that women participated in the “trenches” of factories, as part of “work brigades” to be the “vanguard of production.”

Obstacles arose from the very beginning. Antifascist women criticized the lack of cooperation in factories. Frequently, there was distrust when men saw women doing their jobs. On the battlefield, things regressed. Although women fought alongside men in the early battles, the initial revolutionary impetus slowed, and the situation changed. By November 1936, there were some militiawomen still in the front lines, but their numbers were few. Attitudes toward women changed when the Republican professional army was formed. Traditional command structure came back, and also a distinctly male military hierarchy. Now women were found more commonly in the role of orderlies, cooking and washing behind the front lines.

Yet it is important not to lose sight of the big picture. On the Republican side there could be difficulties, lack of companionship, even hostility from some comrades. All that was part of an open, intensely lived debate. It was an everyday struggle that was unimaginable on the opposite front. In Fascist Spain, certain thoughts could lead directly to prison, if not the firing squad. This was the case of Amparo Barayón, the wife of novelist Ramón J. Sender, who was executed in October 1936. Her short hair and her modern lifestyle made Barayón an expression of “sin” that went against the conventional gender rules. A lesser known case is that of Pilar Espinosa, in Avila, who was shot to death by a Falange squad. Her crime: having a subscription to El Socialista and being a woman “of ideas.”

Antifascist women knew what they stood and fought for. During the years of the Republic they had known a Constitution in which basic rights were guaranteed. Article 36 dealt with women’s suffrage: equal voting rights for all men and women older than 23. The left-wing government introduced civil marriage and divorce. In December 1936, the Catalan autonomous government, in one of the most advanced regulations in Europe, legalized abortion. For this reason, in their conquest of the skies Mari Pepa Colomer and Dolors Vives were not just two exceptional women during an exceptional moment. They were part of a larger historical process, a sign of deep and rapid social change, when women fought and managed to reach spaces previously closed to them in Spain.

In the spring of 1939, after the war is desperately lost, Dolors and Pepa perform final liaison missions to help militiamen and civilians escape to France.

As we know, the story doesn’t have a happy ending. When the war was lost, Mari Pepa crossed the Pyrenees. “All fliers left Spain by plane, of course. From the air we could see long lines of people walking toward France,” she said in an interview in El País from 1984. At first she thought about finding a ticket to Montevideo and joining her father, exiled in Uruguay. Instead, once in Toulouse she married José Carreras, the man who taught her to fly. Together, they would live a last adventure. From France they moved to Great Britain. World War II started and Carreras served in the British RAF, fighting for the second time against air strikes of Hitler’s Luftwaffe.

Dolors Vives, meanwhile, decided to remain in Catalonia. Under Francoism, the time of women fliers was over. Dolors lived a quiet life away from politics, bringing up a family of 10 children. Until her last days, she worked as a piano teacher.

After the dictatorship, Mari Pepa would return to Spain several times from her home in Surrey. Those who knew her describe Mari Pepa as a person of great vitality who never lost her adventurous spirit. Some of her last words, however, show an echo of sadness. “I will never move back to Spain, even though Franco is gone. I do not care. Almost all my friends have died and those who haven’t, live somewhere else in the world.” Dolors, in her last interviews, nostalgically remembered a time when she went, literally, further and higher than anyone: “After the Civil War flying ended, but my memory of that time remains in books and photos. A couple of years”, she said, “I wouldn’t change for anything.”

Miguel Ángel de Lucas is a journalist and working on his Ph.D. in Contemporary Spanish Literature at the University of Sevilla.